European Defence between the Global Strategy and its Implementation

28 Feb 2017

By Félix Arteaga for Elcano Royal Institute of International and Strategic Studies

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageElcano Royal Institutecall_made on 16 February 2017.

Introduction

The High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, unveiled her Global Strategy for the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy (henceforth the Strategy) at the European Council on 28 June 2016.1 It had been commissioned a year earlier, when neither the members of the Council nor the High Representative herself could have foreseen that its delivery date would coincide with the British decision to leave the EU. The unfortunate timing meant that its reception was somewhat muted,2 in stark contrast to the warm welcome given to the first European Security Strategy in 2003.

It was not the first time that a review of this sort has arrived at an inopportune moment. The same thing happened in 2008, when the French President of the European Council proposed overhauling the 2003 strategy3 and could only present a Report on the Implementation of the European Security Strategy4 to the European Council in December 2008, owing to an accumulation of unfortunate circumstances such as the Irish referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon, the war between Russia and Georgia and the financial crisis. But even in those circumstances, the European Council gave its formal backing to the report and issued a complementary declaration in order to underpin what was then known as the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) and to set the EU’s level of military ambition. This time, by contrast, the European Council confined itself to welcoming the Strategy and asking the Council, the Commission and the High Representative to develop it further.

The implementation of the Strategy comes at a time of highly adverse political, economic and social circumstances for the process of European integration, so that its development is not solely reliant on the content of the document or the determination of its backers. The present working paper therefore seeks to analyse the first part of the life-cycle of the Strategy, from its submission to the European Council in 2016 to the review of its implementation by the European Council in December of the same year. Only the content and developments that affect security and defence and are listed in the Index will be dealt with in this working paper. These are not the only or most important ones for the project of integration, but they are those that will make the most of the Strategy in the process of creating a path that has been mapped out for quite some time.

Approach and nature of the Strategy

The Strategy has been created from a foreign policy perspective, framing security and defence aspects within the context of the EU’s external action, setting out the main principles, values and operational patterns of its international conduct. This focus, from foreign policy towards security and defence, represents an advance on the 2003 Strategy, which ran in the opposite direction, seeking to construct global operations on the basis of the EU’s security and defence challenges and threats.5 Since then the EU’s international standing has been steadily consolidating and it now has the means and structures that confirm its status as an international actor; what it needed, therefore, was a foreign policy approach that encompassed its various dimensions, including security and defence.

The EU now possesses a guide that establishes the principles, priorities and goals of its external action, but the Strategy is still a long way from attaining the status of the grand strategies devised by the major powers. It cannot reach such a level because the EU is not yet such a strategic, unitary or autonomous player as they are, and consequently it would be wrong to demand of its Strategy more than is permitted by its nature as a political actor. This is a limitation that should be borne in mind when the Strategy is criticised for its lack of clear strategic objective, defined timeframe or a methodological approach, all of which are features of national strategies.6

The Strategy, just like its 2003 predecessor, does not rank the priorities in a hierarchy, nor does it quantify the tools needed for its level of ambition or explain how ways and means can be found to achieve its goals. The vagueness is unavoidable because most of the resources that can be mustered for its external action depend on the member states and these are subject to their own national security policies. Consequently, the Strategy is a document more of an aspirational than transformational nature, one that seeks to steer rather than determine changes, although, as Lehne points out, the line that separates aspirations from wishful thinking is a fine one.7

In order to be transformative, strategies need to have a binding character and possess a robust system of leadership. National strategies fulfil this role to the extent that they serve to align strategic planning from the highest levels of government to the lower levels of execution. In the case of the EU, fulfilment of its strategies depends on an array of EU, intergovernmental and national players, something that complicates alignment of the strategic chain. The Strategy acknowledges the necessity of better connecting member states’ external action and that of the European institutions (‘a joined-up Union’) and recognises the efforts made to date using the so-called integrated approach. However, the Strategy is not equipped with coercive mechanisms that would oblige member states to align their national proposals with European ones. This does not preclude the member states from voluntarily complying, nor does it rule out that the Strategy will end up facilitating the integration of national and European proposals, but there will always be the risk that their non-compliance will affect the implementation of the Strategy.8

Similarly, the Strategy reiterates the need to connect the internal and external dimensions of EU policies. The lack of connection reflects the fact that these dimensions are compartmentalised between the member states on the one hand and the Commission and the EEAS on the other. Security continues being primarily the competence of the member states, so it is they who decide the extent of their cooperation in the external and internal dimensions of security. Within the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AFSJ) the Commission possesses powers, action plans and strategies that pertain to internal security (the most recent dating from 2015). The Strategy does not try to resolve the discontinuity between the two dimensions, but rather broaden its external security dimension towards certain elements of internal security that would underpin its capacity for taking action, such as integrating the capabilities of the various European agencies in the missions of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). In simplified terms, the Strategy is concerned with the nexus in order to see what internal security can do for external security.

National security strategies address the nexus from both directions, recognising that what happens in the internal sphere also affects their external action. Thus they deem the economic situation, social cohesion and identity as important for their prosperity and security as external challenges and threats. The Strategy identifies some of these, such as terrorism, climate change, financial volatility and energy, but it overlooks the complex reality that the process of European integration is going through and formulates an external action proposal that fails to take the EU’s internal situation into account, despite acknowledging that ‘even its existence’ is being questioned.9

In terms of defence, the Strategy contains elements of continuity and progress relative to the 2003 Strategy. This had come under fire for failing to explain how and for what purpose military force would be used,10 for failing to acknowledge that the decision to use force depended on the member states11 and because between the states there are considerable differences of strategic culture.12 The new Strategy also avoids saying how military force will be used and, unlike the EES, lacks any mention of interventions.13 It makes it clear that NATO is the primary framework for collect defence and appeals to the need to develop the EU’s strategic autonomy, within and outside the former framework, and to promote military and industrial cooperation to develop military capabilities. It does not, however, establish the level of ambition that would determine all the above, nor does it define what terrestrial, aerial, space and maritime capabilities would be needed to cover the entire spectrum of operations being envisaged. For this it refers to a ‘sectoral strategy’, which would need to be devised by the Council but which, as shall be seen below, has never materialised.

Lastly, strategies should be judged by the results they achieve in terms of the evaluation mechanisms that are set and the progress indicators adopted. Such mechanisms are important both for evaluating the results and for adapting strategies and policies to changes in circumstance. The Strategy does not give deadlines for attaining the goals it sets out, nor does it establish evaluation procedures or progress indicators, unlike the EU’s Internal Security Strategy of 2015, which obliged the Commission to send annual reports to the Council and the European Parliament to facilitate monitoring. Its implementation relies on initiatives being taken by the high representative, the Commission and the Council and only envisages the participation of the European Parliament when soundings are being taken for its review, along with the Council and the Commission.

European defence, from the (high) hopes of Lisbon to the (scant) progress achieved

The EU treaty signed in Lisbon generated high hopes because it introduced such innovative measures as a collective defence clause enabling the assistance of other member states to be called upon in the face of armed aggression (TEU Art. 42.7) and the ‘solidarity clause’, which referred to such assistance within the EU (TFEU Art. 222) and beyond it (Art. 43.1) in accordance with the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU. In a more restrictive way, the countries that wanted to were able to take their military collaboration as far as they wished by taking advantage of permanent structured cooperation (TEU Arts. 42.6 and 46 and Protocol 10) or carrying out CSDP missions and operations commissioned by the EU (TEU Arts. 42.5 and 44).

Such expectations failed to become a reality however and the Common Security and Defence Policy turned out to offer neither the commonality nor the security and defence policy that was envisaged in Lisbon. Whether for lack of political will to implement the CSDP or the economic cost of doing so, European defence entered a period of stagnation that turned into regression once the economic crisis took hold. In parallel to this, the unease caused by the uprisings of the “Arab spring” became concern after the emergence of Islamic State and the proclamation of the caliphate in Iraq and Syria in 2014, followed by the terrorist attacks in European cities and uncontrolled flows of migrants across its borders. Nor was the CSDP able to respond to another conflict that erupted in Ukraine in 2014 and, following the Russian intervention on its eastern border, the CSDP’s limitations in tackling Jihadist terrorism became plain for all to see. The concern would have been greater still had Ukraine been a member of the EU or NATO, which would have put the determination and capacity of European defence to the test.14

The pace of the revival was much slower than its backers had wished, however, and every time attempts were made to persuade the Council to bolster European defence its leaders’ attention ended up being drawn to more urgent matters elsewhere. To make up for this, its supporters seized on every crisis that beset the EU, whether stemming from the control of borders, unchecked migration, terrorist attacks, the departure of the UK or the viability of the integration process, to call for greater integration in defence as the answer to such problems.

The Strategy did not bring anything new to European defence other than codifying certain initiatives that were already underway at the time of its creation, but it lacked a ‘sectoral strategy’ to integrate them.15 Therefore such initiatives do not stem from the Strategy, since they predate it, and the implementation of each thus has its own dynamic even though all of them appeal to the Strategy to lend legitimacy to their development. The implementation of the Strategy has turned into a bottom-up exercise, in which the final implementation will be the result of the interaction of the various initiatives. This is quite the reverse of the top-down exercise the Strategy had envisaged, whereby the final implementation would have been guided by the general Strategy and by a specific sub-strategy for defence.

Given the complexity and diversity of the measures to be coordinated, it was expected that the Strategy would delegate the task to a defence white paper,16 even though it would be neither straightforward nor swift.17 Its drafting was necessary because it would not be possible to attain the strategic autonomy to which the Strategy aspired –what the EU can do for itself and for others– without first determining the level of civilian-military ambition or its functions, requirements and priorities, especially when its autonomy had been significantly reduced with the UK’s withdrawal. The High Representative was committed, however, to speeding up the implementation, determining the aforementioned definitions herself with the backing of the Political and Security Committee, replacing the defence strategy that the Council should have drawn up with her own Strategic Implementation Plan on Security and Defence, which is analysed below.18 From then on the implementation initiatives of some member states, the High Representative (Implementation Plan on Security and Defence), the joint NATO-EU declaration19 and the Commission’s European Defence Action Plan emerged, overlapped and contradicted each other.

Among the initiatives to have come from member states the most important are those from German and France. Germany made headway towards a European Union of Security and Defence in its security white paper of 2016.20 It contained various priorities that would later make an appearance in the Strategy: permanent structured cooperation, the ‘Europeanisation’ of the defence industry, a civilian-military operations headquarters –over the medium term– and developing the Strategy through a specific strategy for the CSDP. France, meanwhile, had always been the champion of European defence and advocate of the EU’s strategic autonomy, but at the NATO summit in Warsaw in July 2016 its President, François Hollande, rejected the idea of the EU having its own defence independent of NATO or military commands that would duplicate NATO’s, reducing the level of ambition to undertaking certain initiatives on its own account.21 On the eve of the informal Bratislava meeting in September, the French and German Ministers of Defence sent a joint proposal to the high representative in which they took the opportunity of the UK’s withdrawal to extend the CSDP to 27 members, disposed to creating –albeit over the medium term– a permanent headquarters for missions and operations, promoting permanent structured cooperation, accelerating cooperation between NATO and the EU and enabling the use of shared funds for research.22

At the informal Bratislava meeting the High Representative presented a roadmap for activating the implementation of the Strategy between 2016 and 2017. In the section relating to security and defence, the High Representative gave a foretaste of the essential elements of the Implementation Plan that she would subsequently present to the Council in November. First, it raised the level of ambition, ranging as it did from the management of crises to the protection of Europe. Secondly, it modified the CSDP’s procedures (financing of missions, assessment of threats, coordination of planning) and structures (headquarters, rapid reaction) as well as developing capabilities (development plan, strategic autonomy, industrial base, proposals of the Commission) and strengthening cooperation mechanisms (permanent structured cooperation, NATO-EU, associations). For their part, the President of the European Council, the Council Presidency and the Commission presented a security and defence roadmap confined to two points: implementing the NATO-EU declaration as soon as possible and waiting until the December European Council meeting to decide how to implement the Strategy.23

The security and defence proposals did not arouse universal enthusiasm. Despite Czech, Spanish and Italian support for the Franco-German proposal, other countries, such as Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland, Estonia and Lithuania, expressed their opposition and the others had doubts about the goals or instruments. From that moment on, the High Representative’s tactic for streamlining implementation was to modify or eliminate the proposals that generated most resistance to prevent them from impeding the process. It was a tactic that risked losing in long-term ambition and cohesion what it gained in short-term flexibility.24

To make up for the chilly reception in Bratislava, Italy and Spain met France and Germany in October to form a hard core of support for the High Representative’s implementation. Italy went further than the Franco-German ambition by proposing the creation of a multinational European force and something akin to a ‘Schengen for Defence’, based on a group of countries that could later be joined by the rest.25 The proposal suggested that the EU should acquire and operate defence capabilities, strengthen its institutional, operational and industrial potential and even that the countries wanting to go further could create a Union for European defence.26

The four Ministers signed up to the proposals on permanent structured cooperation, operational and industrial strategic autonomy, defence councils of ministers and a leadership and planning capability (previously headquarters) for missions and operations that would cover the whole range of military intensity. In their letter to the High Representative, the four Ministers supported collaboration with NATO and a greater European role in places such as Mali, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Congo, where they ruled out the intervention of NATO, although they stopped short of creating a European army or multinational forces. Thanks to this four-nation support the High Representative’s proposal managed to win the backing of the Foreign Affairs Council in October, although it stressed the need to involve the member states and the Commission in its development.27

The High Representative finally took her Implementation Plan to the Council in November,28 a plan that, in the opinion of the Political and Security Committee, was compatible with the one the Commission would subsequently present dealing with industrial and financial issues. In their conclusions, the EU Foreign Affairs and Defence Ministers supported the majority of the high representative’s proposals with some minor modifications.29 They also called on the EEAS, the international Joint Chiefs of Staff of NATO and the Commission to present a proposal to the European Council in December 2016 to implement the joint NATO-EU Warsaw Declaration.30

The conclusions of the November Council supported the list of civilian missions and military operations that the High Representative had associated with the new level of ambition: crisis management operations, stabilisation, rapid response, air and maritime security; as well as executive civilian missions, involving reform of the security sector and fostering civilian and military capabilities. Once the former had been agreed, it only remained for the Council to commission the High Representative –not the EEAS, as the EEAS itself had proposed– to submit proposals for the development of civilian capabilities and improve their response capacity. It also asked her –together with the member states that had not included their proposals– for proposals to strengthen rapid response instruments, including battlegroups. The Council did not, however, approve her proposal on permanent structured cooperation and asked her to submit a new one, once the member states express their availability for taking part.

The European Council meeting in December also endorsed the level of ambition proposed by the High Representative and approved by the Council of November, calling upon her and the member states to develop it further. In forthcoming months they will have to specify how they intend to coordinate military planning (annual coordination meeting), how industrial, technological and research aspects of military capabilities will be developed, how the rapid response capability will be updated, the terms of the permanent structured cooperation and the way in which the capability of contributing to the security and development of neighbouring states is going to be improved (see the final Annex). Had a defence strategy or white paper been drawn up earlier as the Strategy suggested, all the details mentioned above would have been agreed at the same time. Probably it would have taken longer to agree all the aspects at once, but only probably, because now it remains to be seen when and how so many unresolved issues are agreed.31

The industry, capabilities and financing of security and defence

People have been calling for the revitalisation of the industrial and technological base of European defence in recent years for a variety of reasons and rationales. The greatest drive in this direction coincides chronologically with a fall in European defence budgets and the reduction in European demand for industrial capabilities.32 The issue of budget cuts was taken up by the US, which demanded that its European allies bolstered their economic efforts, taking advantage of opportunity presented by the NATO Summit in Wales in 2014. A commitment was made to targets earmarking 2% of GDP to defence spending and 20% of this spending to investments on equipment, which, however, has not been transferred to the sphere of the EU.33 The member states most affected tried to remedy the industrial crisis, and hence the European Council of December 2012 asked the High Representative, the EEAS, the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the Commission to mobilise to strengthen the CSDP, develop the pending civilian and military capabilities and reactivate the competitiveness of the European industrial base.

The Commission, which the member states had traditionally kept apart from industrial defence policy citing reasons of national security to protect their defence industries from the single market (TFEU Art. 346), issued a Communication in 2013,34 in which it put itself forward as an catalyst, offering itself to promote, finance, acquire and even operate defence equipment, in a strategic sector for the EU (€96 billion, 400,000 people directly and 960,000 indirectly employed in 2012). To this end it presented a package of measures that, in principle, would encourage the liberalisation, competitiveness and financing of the industrial sector, accelerate industrial concentration and enable access to R&D funds earmarked for regional development and civil research. Although two defence directives had already been issued on procurement (2009/81) and transfers (2009/43), the Commission now proposed to broaden and deepen the liberalisation of the procurement market and finally put an end to national preferences in tendering (75% of the total), as well as prohibiting offsets and restricting mechanisms such as government-to-government sales, those falling under international agreements that escape the control of the EU internal market.

A European Council meeting was called in December 2013 –which was originally going to deal with only one subject– to underscore the importance of defence. The revitalisation of defence had two rationales: that of capabilities, led by the large countries and industrial sectors, together with the Commission and the EDA; and that of policy, led by the High Representative and certain countries, among them Spain. The first, capability-driven, wanted the EU to develop equipment, command and control and market capabilities that European defence lacks, while the second, strategy-driven, wanted first to know what these capabilities were needed for. The Council managed to balance both rationales acknowledging that security policy could not be subordinated to military capabilities, but rather that coordinated progress had to be made on both rationales, and hence from then on a strategy would be sought that would enable the progress of the CSDP.35

In order to execute the December European Council’s instructions,36 in 2014 the Commission drew up a roadmap to facilitate the defence industry’s access to R&D funds from which it had been excluded, for which it had to create a special line of finance using a Preparatory Action in collaboration with the EDA and an Advisory Group of high-ranking experts.37 This would enable the defence industry to access specific technological research funds in 2017 before it would be able to access those of the Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-2027). Later it drew up another implementation report in May 2015 in order to acquaint the European Council of June 2015 with the progress made since 2013.38

The Strategy incorporated the aforementioned gains and endorsed the European Council meetings’ proposals while awaiting the Commission to present its European Defence Action Plan in December 2016. In particular, the Strategy affirmed the principles of industrial cooperation, as the rule and not the exception, in procuring capabilities, as well as that of complementarity, so that the contribution of European funds should not be offset by a reduction in national funds. For the development of the capabilities needed for strategic autonomy, the Strategy called for a 20% target for collective investment in equipment and R&T (far from the 35% originally agreed), an annual review of the coordination of national planning and the drafting of a new capabilities plan for the EDA in 2018.

In her Implementation Plan, the High Representative, who also leads the EDA, reiterated the need to develop the EU’s assets in their industrial and financial dimensions (European Councils of 2013 and 2015, the EDA’s Capabilities Development Plan of 2014 and proposals from the Commission) but giving the EDA an important role in determining the capabilities stemming from the Strategy and in the coordination of national planning. In its conclusions, and without downgrading the role of the EDA, the Council called on the member states to share these tasks, on the grounds that both the definition of the level of ambition of strategic autonomy as well as the military capabilities deriving from it are political by nature.

Finally, the Commission presented its European Defence Action Plan.39 Its goals were stimulating demand by incentivising investment, advancing towards strategic autonomy by developing military capabilities and strengthening industrial competitiveness by supporting research. In accordance with its principles, the Commission set out its investment measures as a way of stimulating those of member states, not as a means of discouraging them, and always in accordance with the treaties. This affirmation was important because the Commission reiterated in its Plan the need for the European Council to explicitly delegate the competences it lacked in order to develop its proposals. These were summarised as providing funds for European defence,40 ensuring investment in the supply chain and strengthening the single market.

Figure 1 shows how the funds envisaged are to be distributed and governed. It is important to stress that these are financial instruments, not EU common funds, so that they come under national budgets. The financing covers all phases, from research to procurement, but the procurement is not carried out by the EU; rather this is done by the member states by aggregating their national contributions. The EU is confined to supporting these investments to the extent its competences and possibilities allow, provided they are necessary to attain strategic autonomy and they are made in cooperation among member states. They do not serve to develop any capability therefore, but rather those that are decided by the Coordination Board, made up of the member states, the High Representative, the Commission, the EDA and the industry, as shown in Figure 1.

Below the Coordination Board there are two sections: one for research and one for joint capabilities. The first shows the amounts envisaged for investing in defence research from 2017 (€25 million) to 2020 (until reaching the €90 million of the Preparatory Action). If this experience works, the Commission estimates that €500 million should be earmarked annually for a European Programme of Defence Research, an amount always contingent on the final total of the Multiannual Financial Framework from 2020. Such funds will be managed under the auspices of the Coordination Board but borne by the member states, the Commission and industry.

The second section shows the financial instruments available to the member states to stimulate the development of joint dual-use capabilities including post-research phases, which encompasses prototypes and the development and purchase of products and technologies. The capabilities will also be governed by the directives of the Council, although each project will be managed by the participants. The annual figure of €5 billion reveals the importance placed on encouraging cooperation on joint capabilities, although a more precise estimate is still pending.

Figure 1. European Defence Fund (management and amounts)

To ensure investments in the supply chain to small and medium-sized enterprises, the Action Plan offers European Investment Bank (EIB) loans and guarantees using the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI) and the Programme for the Competitiveness of Enterprises and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (COSME). Joint funding is also offered with European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) provided that the rules of such funds, the European Investment Bank and the treaties are observed. The plan also envisages the development of regional clusters of excellence and the attraction of talent. Lastly, certain measures related to the strengthening of the single market for defence and ensuring the aforementioned supply chain are to be developed.

The December meeting of the European Council acknowledged in its conclusions the need to do more and devote more resources to defence, but “taking into account national circumstances and legal commitments”, which diminishes the level of budgetary effort involved in the implementation plans.41

The internal-external security connection (nexus)

The Strategy acknowledges the existence of a nexus connecting internal and external security. This acknowledgement reflects one of the greatest problems of contemporary security because, while it is accepted that there should not be frontiers between the two, the traditional cultures of external and internal security vie with each other to occupy the nexus and create problems of allocating new competences among existing institutions. Various security cultures coexist in the EU. That of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice is shared by the Commission and the member states’ political and legal systems, supported by such agencies as Europol, Frontex and Eurojust. This culture has its own Internal Security Strategy, with medium-term action plans and its own powers from the Commission that are complemented by cooperation procedures among member states. The culture of security and defence has the high representative, the Foreign Affairs/Defence Council, supported by the European External Action Service and the crisis-management bodies of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). It possesses the Global Strategy and, as has been seen, various plans for implementing it.

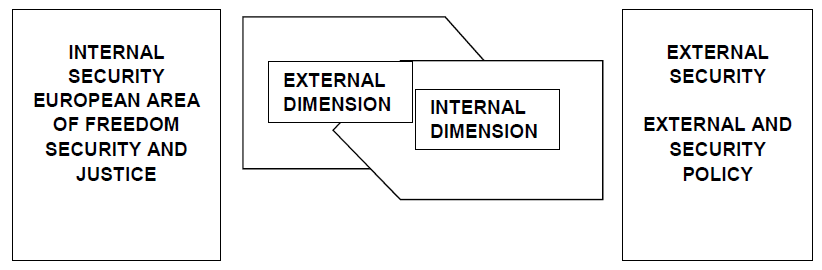

In terms of the schema set out in Figure 2, two processes coexist in the EU: one is an internal policy that unfolds towards the European and international framework (internationalisation), developing its external dimension, and the other is an external security policy that now with the Strategy seeks to develop its internal dimension (internalisation). Both processes necessarily overlap at some point because they share the same objectives (citizens’ security) and in terms of their rationales of expansion (security beyond/within borders affects security within/beyond those same borders).

Figure 2. The internal-external nexus of European security

The first process takes chronological precedence. Intergovernmental cooperation in matters of justice and domestic issues date back to the 1970s and is as old as European political cooperation itself –predating the CFSP– although the existence of the AFSJ was not recognised until the EU treaty signed in Amsterdam, at the same time as the European Security and Defence Policy, forerunner of the CSDP. Such cooperation has stemmed from intergovernmental collaboration and on the sidelines of the EU (Trevi, Schengen, Prüm) between those who wanted to go beyond the provisions of the treaties, in order to pool their experience.

The treaties offered the defence arena the possibility of following the same path: enhanced cooperation in Maastricht and permanent structured cooperation in Lisbon, but the member states have not tapped into its potential. For its part the Commission has been taking on the task of exercising the new EU competences related to border control, asylum, immigration and judicial cooperation, and currently has two commissioners: one for migration and home affairs and another for what is termed the Security Union. All the above issues have an external dimension undertaken both by the Commission and the responsible representatives of the member states, supported by the Standing Committee on Internal Security (COSI), created in Lisbon (TFEU Art. 71).

Just as those responsible for external security drew up a European Security Strategy in their day to stake the EU’s claim as a global security player in the post 9/11 context, those responsible for internal security decided in 2009 to take advantage of the launch of the Stockholm Programme to draw up an Internal Security Strategy (ISS),42 updated in April 2015 for a new ISS.43 Overseeing its implementation is the responsibility of COSI and there have been successive strategies and action plans building on preceding ones.44

The Strategy makes headway in its internal dimension in order to strengthen the external capabilities with the internal security instruments that are needed for it.45 It does not seek to encroach on the competences of internal security, but the internal dimension of the Strategy and the external dimension of the ISS necessarily overlap in terms of their natural scope, as is evident from Figure 2. The Strategy omits any reference to the ISS and any integration between the two. Several analysts (Drent and Zandee) were hoping that the orientation of the internal-external security nexus would be resolved with the sectoral strategy that has been ruled out. The need to reconcile the two strategies is however mentioned in the Implementation Plan that the High Representative presented to the Council in November. This put forward the idea of coordinating the implementation of the two strategies via the joint leadership of the Political and Security Committee and COSI, with the participation of the EEAS and the Commission. However the collaboration between the two committees, which had already been taking place periodically prior to the Strategy, is an asymmetrical collaboration, given that COSI has only an operational mandate, meaning it is not at the same level of strategic cooperation as the Political and Security Committee.

The High Representative outlined her ideas for bolstering the nexus between the internal and external policies in Bratislava, but they were confined to strengthening the synergy and cohesion between the two. Her roadmap for 2016-17 featured initiatives related to emigration, the fight against terrorism and the updating of the Maritime Security and Cybersecurity Strategies. Later, in her November Implementation Plan, she reiterated the importance of confronting external insecurity in order to ensure internal security, supporting countries in their fight against terrorism and organised crime, increasing the interaction between CSDP actors and those of the AFSJ, developing strategies that cut across both such as cybersecurity, maritime security and hybrid threats and exploring the possibility of collaborating on the solidarity (TFEU Art. 222) and mutual defence (TEU Art. 42.7) clauses.

The Council’s conclusions endorse these lines of approach and sum up the CSDP’s contribution to internal security: running missions and operations beyond its borders to provide stability and resilience to neighbouring countries and, in this way, helping to ensure European citizens’ security and protection.

Conclusions

The European Council meeting of December 2016 provides European defence and security with various agendas, apparently compatible and coordinated, but managed in a parallel fashion and lacking an agreed strategy determining their ultimate ends. The goals of each are set out in the Annex, together with the estimated date of execution.

Taken as a whole, the changes in the EU’s security and defence arrangements are not revolutionary and the Strategy has the merit that it has enabled certain plans that had previously been frozen to be reactivated, such as those stemming from the Treaty of Lisbon, or in the course of development, such as those of the Commission and European Council to revitalise the EU’s defence and industry.

Presented in the midst of an existential crisis regarding the EU’s foundations and future, in the wake of internal crises owing to unchecked immigration and a succession of terrorist attacks, and beset by the disorientation brought on by Brexit, the supporters of the Strategy have been able to present it as a solution to such problems. Although they have not fulfilled their promise of creating a ‘sectoral strategy’ for guiding its development, they have managed to secure the backing of the Commission and the European Council for the various implementation proposals that have been presented. And although these bodies will follow its development closely, they have refused to make their own judgement as to the threats to security and defence that are being faced.46

On the other hand, some of the expectations regarding what the Strategy can deliver have been exaggerated (European army, operational headquarters, strategic autonomy, resilience and protection of citizens). Furthermore, the spending commitment taken on in NATO by its member states has not been reiterated. And although there is a call for greater use of the common funds in the CSDP, the reactivation of European defence still falls on the budgets of those member states that decide to participate in it. Nonetheless, the taboo of financing defence has been broken, and although its funding has not been normalised, the door to doing so has been opened, extending the financing of the deployment of battlegroups, increasing the amount of pooled spending on operations.

Although no sectoral strategy has been devised, the development of the Strategy is for the time being reconciling the various implementation initiatives without major problems. In particular, it is worth highlighting the progress in reactivating cooperation between NATO and the EU, and the expectations of cooperation that have opened up between the Area of Freedom, Justice and Security and the Foreign and Security Policy. The division of labour now seems more cordial: NATO is in charge of collective defence and the management of major military crises, the EU of the management of missions and civilian-military operations beyond its borders and the AFJS of security within them. If everything goes according to plan, and the development process is not hit by the grave circumstances affecting the European process of integration, the implementation of the Strategy may strengthen, albeit over the medium term, greater strategic autonomy for the EU. Such a development will benefit both transatlantic ties (balancing burdens and responsibilities on both sides of the Atlantic) and the internal-external nexus (integrating the processes of internationalisation and internalisation of both spheres of security).

ANNEX. State and implementation expectations of some of the measures stemming from the Strategy

Notes

1 ‘Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy’, http://eeas.europa.eu/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf.

2 Among others, Dick Zandee (2016), ‘EUGS: from design to implementation’, AP, nr 3, Clingendael, 3/VIII/2016; and Félix Arteaga (2016), ‘¿La Estrategia Global de la UE? … déjela ahí’, Blog Elcano, 29/VI/2016.

3 The ESS was passed on 12 December 2003 and its text can be found at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/78367.pdf.

4 ‘Report on the Implementation of the European Security Strategy – Providing Security in a Changing World’, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/reports/104630.pdf.

5 Félix Arteaga (2009), ‘La Estrategia Europea de Seguridad, cinco años después’, ARI nr 15, Elcano Royal Institute, 22/I/2009.

6 Annegret Bendiek (2016), ‘The Global Strategy for the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy’, SWP Comments nr 38, August, p.1.

7 Stefan Lehne (2016), ‘The EU Global Strategy, a Triumph of Hope over Experience’, Carnegie Europe, 4/VII/2016.

8 For how the lack of coercive mechanisms affects the implementation of the EU’s Maritime Security Strategy, see Lennart Landman (2015), ‘The EU Maritime Security Strategy’, Clingendael Policy Brief, April, pp. 2-3.

9 Jean-Claude Juncker (2016), ‘Towards a better Europe, a Europe that protects, empowers and defends’, State of the Union speech, Strasbourg, 14/IX/2016.

10 Mary Kaldor & Andrew Salmon (2006), ‘Military Force and European Strategy’, Survival, vol. 48, nr 1, Spring, pp. 19-20.

11 François Heisbourg (2004), ‘The European Security Strategy is not a Security Strategy’, in Everts, Steven et al. (eds.), A European Way of War, Centre for European Reform, London, pp. 27-39.

12 Lawrence Freedman (2004), ‘Can the EU Develop an Effective Military Doctrine?’, in Everts, Steven et al. (eds.), A European Way of War, Centre for European Reform, London, p. 14.

13 Stephan Lehne (2016), ‘The EUGS, a Triumph of Hope over Experience’, Carnegie Europe, 4/VII/2016.

14 Paradoxically, the Russian aggression had the effect of reinforcing US commitment to European security, a commitment that had been called into question with the announcement of America’s strategic pivot towards the Pacific.

15 Daniel Fiott (2016), ‘After the EUGS: connecting the dots’, EUISS Alert, nr 33, July, p. 1.

16 Javier Solana (2016), ‘On the way towards a European Defence Union. A White Book as a first step’, European Parliament, Committee on Foreign Affairs and Sub-Committee on Security and Defence, 18/IV/2016; Margrient Drent & Dick Zandee (2016), ‘After the EUGS: mainstreaming a new CSDP’, EUISS Alert, nr 34, July, p. 1; and ‘European Defence: from strategy to delivery’, Global Affairs, 11/V/2016.

17 Daniel Keohane & Christian Mölling (2016), ‘Conservative, Comprehensive, Ambitious, or Realistic? Assessing EU Defense Strategy Approaches’, GMF Policy Brief, nr 41, p. 39.

18 Sven Biscop (2016), ‘All or Nothing? European and British Strategic Autonomy after the Brexit’, Egmont Paper, nr 89, September, pp. 2-3 and 7.

19 ‘Joint Declaration of the President of the European Council, the President of the Commission and the Secretary General of NATO, 8 July 2016’.

20 ‘White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr’, 13/VII/2016, pp. 72-76.

21 Warsaw, 9/VII/2016, http://www.elysee.fr/conferences-de-presse/article/conference-de-presse-du-president-de-la-republique-lors-du-sommet-de-l-otan/.

22 ‘Revitalizing CSDP towards a comprehensive, realistic and credible Defence in the EU’, September 2016, https://www.senato.it/japp/bgt/showdoc/17/DOSSIER/990802/3_propositions-franco-allemandes-sur-la-defense.pdf.

23 ‘Bratislava Declaration’, 16/IX/2016.

24 For example, the longstanding call for a permanent operating headquarters for operations turned into a planning and leadership capability for joint missions and operations of a civilian and military nature that the November Council subsequently ruled out using in operations. Even when the Strategy was being drawn up, the High Representative chose deliberate ambiguity to avoid opposition to more explicit defence formulations (Biscop, 2016, p. 7).

25 Paolo Gentiloni & Roberta Pinotti (Foreign Affairs and Defence Ministers, respectively) (2016), ‘L’Italie appelle à un Schengen de la dèfense’, Le Monde, 11/VIII/2016.

26 Speech of the Defence Minister, Roberta Pinotti, ‘Italy’s Vision for a Stronger European Defence’, Brussels, 11/X/2016.

27 Conclusions, ‘Outcome of the Council Meeting’, Foreign Affairs, 17/X/2016.

28 ‘Implementation Plan on Security and Defence’, 14/XI/2016.

29 Conclusions of the Council on ‘Implementing the EU Global Strategy in the area of security and defence’, 14/XI/2016.

30 ‘Statement on the implementation of the Joint Declaration signed by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission, and the Secretary General of NATO’, 6/XII/2016.

31 For example, the European council of December abandoned the deadline that had been set (the first six months of 2017) to approve capacity building in support of security and development (CBSD) of third-party countries.

32 Government demand for the European defence industry fell 19% between 2001 and 2010 and investment in R&D fell 14% between 2005 and 2010.

33 Both the Strategy and the implementation documents refer to these percentages as though they were linked to all EU member states, whether allies or not, when in fact they are not targets approved within the framework of the CSDP (the most similar thing is the old commitment made in the EDA to earmark 35% of investments for cooperative projects).

34 Communication 542, ‘A new deal for European Defence and Security. Towards a more competitive and efficient Defence and Security Sector’, 24/VII/2013.

35 At the Council meeting of December 2013, collaboration projects in critical military capabilities were approved such as mid-air refuelling, cyber-defence, remotely-piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) and governmental satellite communications (GOVSATCOM). Moreover, it asked the Commission to study a system that would ensure the security of supply of member states in critical supply chains.

36 See Félix Arteaga (2013), ‘El Consejo Europeo de diciembre de 2013: repercusiones para la industria y la defensa de España’, ARI, nr 46, Elcano Royal Institute, 27/XI/2013.

37 ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM (2014) 387 24 June 2014 on A new deal for European defence. Implementation Roadmap for Communication COM (2013) 542. Towards a more competitive and efficient defence and security sector’.

38 Félix Arteaga (2015), ‘La base industrial y tecnológica de la defensa española y europea ante el Consejo Europeo de 25-26 de junio de 2015’, Elcano Royal Institute, June.

39 ‘European Defence Action Plan, COM (2016) 950 30 November’.

40 ‘European Defence Action Plan: towards a European Defence Fund’, 30/IX/2016.

41 For example, the decision regarding greater funding of military operations through the Athena mechanism, which finances certain shared expenditure (around 10%-15%), is postponed until the end of 2017.

42 ‘EU Internal Security Strategy’, 10/VI/2010.

43 ‘Internal Security Strategy’, http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9798-2015-INIT/en/pdf.

44 Among recent internal security sub-strategies there are the Maritime Security, Information Management, Cybersecurity, Drugs, Fight against Radicalisation and Terrorist Recruitment, and Customs strategies. Among the update plans there are the European Security Agenda of April 2015, the Action Plan on Firearms and Explosives of December 2015, the Plan to combat Terrorist Financing of February 2016 and the Communication on Smarter Information Systems for Borders and Security of April 2016.

45 Javier Solana (2016), ‘Hacia una seguridad europea efectiva’, El País, 17/IX/2016.

46 According to Art 222.4 of the TFEU, the European Council will periodically assess the threats faced by the EU. This article has not been activated either for internal or external security.

About the Author

Félix Arteaga is a Senior defence and security analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.