Russian Analytical Digest No 199: Making Social Policy in Contemporary Russia

6 Mar 2017

By Marina Khmelnitskaya and Irina Olimpieva for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 27 February 2017.

The Role of Policy Experts in Social Policy-Making in Russia: The Case of Housing

Abstract

Policy expertise and policy experts are expected to play an important role in the policy-making process, both around the world and in Russia. However, the patterns of long-term policy shifts involving technical expertise are insufficiently understood. To what extent do experts influence policy in Russia? To date, this question remains unanswered. These issues are considered here in the case of housing policy

Ideas and Interests in the Russian Policy Process

Comparative research argues that the influence of experts is “real but limited”. Key decisions about the choice between policy alternatives, specifically including “big” ideas that guide policy, often described as policy paradigms, are taken within the realm of politics and relate to the issue of political authority. Moreover, when decisions relate to the choice of policy instruments— which represent elements of policy of a smaller magnitude—coherent policy plans put forward by experts sometimes change beyond recognition under the influence of diverse stake-holders in the process of policy adoption and policy implementation. For this reason, many expert proposals never get off the ground.

In the context of Russian politics, this view of the policy process and expert influence over it are intensified further by the particularities of Russia’s non-democratic political system. The personalist dimension of the Russian decision-making process, involving the personal charisma of the Russian president projected through the media, and his central position within the vertically organized, informal governance networks define one important strain of the literature on decision-making.

The “institutionalist” view of policy-making in Russia complements the personalist perspective by emphasizing a more nuanced role of bureaucratic policy actors. This view holds that a more regularized bureaucratic procedure for making policy decisions is as important as the personal interventions of the president. In the absence of the genuine representation of popular interests in Russia, bureaucratic groupings, such as the social and economic- financial blocs of the government, act as proxy defenders of respective constituencies within Russian society. When making everyday adjustments to policy or choosing between alternative policy instruments, these actors become interlocked in a protracted policy battle and often endless policy consultations. In this respect the annual budgetary process provides one set of policy deadlines which push actors to make policy choices. The president prefers to interfere only in exceptional circumstances when no side is prepared to take responsibility for crucial decisions—for instance with the decision to forego the second indexation of pensions during the 2016 budgetary process. In this way, the president uses his political capital sparingly, seeking to maintain his political authority.

Both the “autocratic” and “bureaucratic” perspectives allow a role for technical expertise and policy experts to influence policy; a more subservient role from the first perspective and a more active one—from the second. From the first perspective, the legitimacy of the state in Russia is, to an important extent, technocratic, i.e. deriving from the claim of “doing the right thing for the country”, rather than being based on democratic procedure. In this light, the recent return of Alexei Kudrin to “official politics” serves as a good example. At the end of May 2016 Kudrin was elected Deputy Chair of the Presidential Economic Council and took a leading role at the renowned Center for Strategic Development (CSR), the organization responsible for developing Vladimir Putin’s first pre-election program in 2000, which became known as the “Gref Program”. Kudrin, with his colleagues from the Committee for Civic Initiatives (KGI),1 and other highly qualified experts from research organizations as well as from government ministries, are currently working on a new strategy for the country’s development after 2018, which is positioned to become Putin’s campaign platform for the 2018 presidential elections. This association with qualified experts contributes to the legitimacy claim of the current leadership, that finds itself in a highly complex domestic, economic, and international setting.

Such developments are not without historical precedent. At complex moments of leadership transition, Russian leaders have tended to form centers of extra-departmental expertise whose staff later were often appointed to key government jobs. This was the case with the CSR at the start of Putin’s presidency. Several of the CSR experts, notably Herman Gref and Elvira Nabiulina, have since occupied important policy-making positions. Similarly, the Institute for Contemporary Development (INSOR) think-tank was associated with the start of Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency in 2008 and the four National Priority Projects. The joint team of the Higher School of Economics (HSE) and the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) produced Strategy 2020 in 2011 at the start of Putin’s third presidential term. At the same time, historical examples also demonstrate that experts become easy scapegoats for policy failures. For instance, the failure of the initiative to monetize inkind benefits (l'goty) that led to mass protests in 2005 was blamed on liberal policy-makers in and outside the government and their poor policy designs.

Yet another dimension of technocratic governance in Russia which helps to elaborate the second, institutionalized, view of the policy process is associated with what we may describe as knowledge monopolies that emerge around Russian executive structures. A historical process tracing of policy developments in specific policy spheres is needed for the analysis of this phenomenon and its change over time. We may distinguish among its several aspects. Specifically, recent studies have found that in Russia the rates of rotation by government staff among individual ministries are low. This stability of personnel creates insular specialist cultures and monopolies on policy expertise within individual ministries. Such monopolies, however, extend beyond executive institutions to involve experts at research institutes and NGOs working in different spheres of economic and social policy. The presence of informal inter-personal networks, an important feature of the Russian institutional setting, is responsible for producing close bonds among state ministries and specific groups of non-state policy experts.

Within individual areas of policy—I will consider the example of housing policy below—a tight network of expert policy “insiders,” including state officials and non-state policy specialists, represents the core of the policymaking community. Policy ideas shared by this group provide the basis for policy elaboration at any given time. The central position of well-connected experts, moreover, allows them access to greater economic and administrative resources compared to the experts located on the fringes of the policy community. All actors belonging to the overall community in a given sphere are usually well aware of differing policy proposals put forward by competing “advocacy coalitions”. They regularly take part in joint scientific conferences and events. Yet, it is the views of the tight policy network in the middle of the specialist community with close ties to the branch ministry that has real influence over formulating policy proposals and writing policy documents.

This pattern is usually only deepened by the presence of international cooperation. Particularly, in the 1990s but in the subsequent period as well, the network’s core in Russia had greater resources to establish and sustain such cooperation. At the same time, research finds that international agencies have an affinity to choose well connected local expert partners. This only further reinforces the established knowledge monopolies.

What becomes difficult under such circumstances is change in policy ideas and consequently policy change itself, particularly the paradigmatic replacement type of change referred to earlier. Three mechanisms can be identified describing how such change can occur. One of them involves the perceived failures or limitations of earlier-adopted policies that are revealed at the stage of policy implementation. Failures lead insider experts to adopt alternative ideas and/or to the inclusion in the central network of previously marginalized experts and their proposals. Another mechanism relates to changes in policy-related knowledge disseminated through international policy communities and international contacts. The third kind of influence is the increased proximity with parallel policy networks active in neighboring policy domains. When any of these dynamics coincide— change is more likely.

The connection between specialist policy ideas and political actors’ material interests is important. Knowledge monopolies in Russia are sustained because their proposals fit with, and are supported by, the material interests of powerful policy actors: the blocs and groupings within the Russian government and the Russian president. Yet, the affinity between the politicians’ interests and ideas emanating from expert advisors should not overshadow the important independent impact of specialist proposals on policy formation. Interests, in political popularity for instance, and internalized beliefs of the most powerful political actor in Russia, the president, matter greatly for the chances of policy proposals to be implemented. Yet, an evolution in expert ideas can also precede a change in interests, as the case of Russian housing policy below demonstrates.

Experts and Housing Policy-Making

Within the housing sphere in the 1990s, private housing ownership was prioritized by the network that emerged around the branch ministry, the Ministry of Construction (Minstroy). This policy preference was part and parcel of the international advice given to the Russian government at the time and supported by international housing advisors. To be fair, other forms of housing ownership— rented and cooperative types of tenure—were included in policy documents by the policy-makers as well, but without being prioritized. Housing privatization to current tenants that turned them into a class of property owners chimed well with the overall thrust of the post-socialist economic restructuring process, which emphasized the private ownership of economic assets. A large proportion of the public liked the idea of becoming owners of their apartments. Yet, there remained a significant minority who preferred not to privatize.

By 2000 the policy vision based on the predominance of private ownership was successful to a degree: 60 percent of housing became privately owned, leaving 40 percent in municipal ownership. Among the group who preferred to remain municipal tenants, many were wary of high property taxes that could be imposed on private housing, and of being made responsible for the costs of expensive major repairs of apartment buildings where most were situated. Given the poor state of repair of a large part of the housing stock in Russia this was a frightening prospect. Introduction of property taxes and the transfer of the costs of major repairs from the state to private owners were among the instruments belonging to the private ownership paradigm and advocated by the policy network.

These policy plans did not materialize during the 1990s though, partially because of the weakness of the Russian state administration combined with opposition from the State Duma to the introduction of a liberal new Housing Code developed by the network of experts in and around Minstroy. During the 2000s the capacity of the state increased, while the attenuation of Russian democracy meant the election of a compliant parliament, allowing the adoption of the new Housing Code in 2004. The Code made major repairs a responsibility of apartment owners and reduced the entitlement to free municipal housing provision to the poorest five percent of the population. Yet, the populist motives of the authorities and the availability of resources allowed a statist solution to the problem of expensive “capital repairs”, through the establishment of a dedicated state Foundation, to be used in the second half of the 2000s.

However, the vision of housing policy based on the predominance of private tenure, promoted by the housing network, reached a dead-end in relation to the affordability of mortgage funding for the majority of the Russians who needed to improve their housing conditions. Mortgages offered by Russian banks remained unaffordable to the majority of the public. Thus, in the mid-2000s, after the adoption of the new Housing Code, the failure of the idea of mass housing ownership in Russia became widely perceived by the public and by the expert community. We may also describe this period, starting in 2005, as the end of the dominance of the private ownership paradigm and a turning to a new model of mixed ownership in Russia.

In addition, in terms of the interests of influential policy-makers, 2005 was also marked by social protests against the monetization of benefits and indicating public anxiety surrounding reforms in the social sphere generally, including housing. This contributed to the greater openness of the political leadership to alternative expert ideas proposing new avenues for social reforms.

From this time onwards, alternative policy experts advocating the use of rental and cooperative tenure forms in addition to the private form found a place in housing networks. Thus, in the policy documents adopted since the late 2000s—including different versions of the state program “Affordable Housing”,2 the May 2012 decree N600 on housing, and the 2016 new priority projects— the development of rental housing and cooperatives, particularly rentals, is invariably emphasized. Even an idea to set up a special state corporation for the development of rental housing was considered in 2011–12, but was not followed through.

In addition, there was stronger coordination with other networks in social and economic spheres to improve the affordability of mortgage finance. This involved making the terms of mortgage borrowing more affordable (with assistance from state banks and the government mortgage Agency, AHML) and increasing the income levels of the public, particularly those employed in the public sector.

The fact that these ideas have been poorly implemented in reality (i.e. the development of rental housing) between the late 2000s and the current economic crisis3 is due to the influence of political interests. More precisely, due to the contradiction between the interest to produce affordable housing options for families with different levels of income and the pursuit of political popularity. Specifically, the free privatization of state housing—which by 2017 increased the share of private ownership in Russia to over 90 percent—was extended numerous times. This has meant that the local municipalities lacked incentives to invest in the construction of new rental accommodation or upgrade existing rental housing stock. These at any point could be “lost” to privatization. The current period of economic crisis and the squeeze on public finances has led to efforts to increase the collection of property taxes on housing and land. These higher costs made the ownership option less attractive to the remaining tenants and reduce the political costs of ending housing privatization.

In January 2017 the State Duma voted to end the policy of “free for all” housing privatization in the country, a move which could have concluded a 25-year history of an unprecedented free distribution of state housing property in Russia. However, by mid-February the deputies had changed their minds under the influence of President Putin, who had perhaps concluded that this decision could be damaging to his political popularity. The law about permanent housing privatization was signed by the president at the end of February. This decision was dictated by the political interests of Russia’s top leaders and has, for now, undermined the implementation of alternative expert ideas with regard to the development of housing rents. While policy efforts in this direction will continue, they will be complicated by the continuation of privatization.

Conclusion

What makes the area of housing different from that of pension provision, for example, is the fact that housing is a highly localized policy sphere. Local and regional authorities provide the lion’s share of budget funding (for the upkeep of municipal housing and communal areas of multi-apartment blocks) and a multitude of housing construction and maintenance firms work in the housing sphere. This means that at the federal level there were no powerful stake-holders to oppose the ideas of alternative policy experts and block their introduction in legislation, apart from those of the top leadership, which I have just addressed. In the area of pension provision, by contrast, where most funding is distributed at the federal level (by the Pension Fund of Russia and increasingly the state budget), the battle between defenders of the old pay-as-you- go system and the alternative model based on private savings has been intense in recent years. The 2016 budgetary policy cycle was no exception.

Many scholarly analyses of the Russian pension reform process have emphasized the interest-related side of this policy dynamic. A focus on policy expertise and experts in this area as well as in other areas of policy in Russia may reveal the presence of knowledge monopolies, the bifurcation of policy communities supplying ideas to the policy process and their transformation over time. Attention to such important knowledge-related elements of the policy process can help a better understanding of the trajectories of policy shifts in individual areas of policy in Russia.

Notes

- Formed by Kudrin after his resignation from the government in 2011, following a dispute with Dmitry Medvedev over budget priorities.

- Latest version from April 2014.

- The crisis hit the mortgage market in late 2014, which required the state to intervene with a Program of state assistance, and reached housing construction with a delay in 2016.

About the Author

Marina Khmelnitskaya is Post-doctoral researcher at the Centre of Excellence in Russian studies: Choices of Russian Modernization, Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki. Her research is concerned with politics and policy-making in Russia, as well as housing policy and housing finance. She is the author of “The Policy-Making Process and Social Learning in Russia: the Case of Housing Policy” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Russian Trade Unions between Neo-corporatism and Direct Political Involvement: The “Dual” System of Labor Interests’ Representation1

Abstract

This article outlines the design of the “dual” system of labor interests’ representation in Russia, which comprises two “parallel” institutional mechanisms used by trade unions to participate in policymaking: the formal neo-corporatist system of social partnership and the informal institution of direct political participation. The analysis suggests that Russian trade unions have achieved more influence in policy-making through informal political channels and tools than via formal social partnership institutions. The assessment of the real impact of trade unions on labor and social policy is difficult, because of the informal character of the direct political participation. However, we assume that it is underestimated and requires further research.

Social Partnership as a Neo-corporatist Institution of Labor Interest Representation

Social partnership (SP) is a neo-corporatist institution for labor interest representation. The core of the social partnership model is the ideology of social dialogue aimed at coordinating the contradicting interests of labor and capital via the inclusion of trade unions and employers’ associations in policymaking. In practice, the process of interest coordination takes the form of negotiations between “social partners” and the state within the framework of tripartite commissions and results in so-called social pacts—formal multi-policy agreements among governments, unions, and employers. Before 1989, social partnership was primarily a phenomenon of continental Western Europe. After the collapse of communism, the model was introduced in Russia (as well as in other Eastern European countries) to become the foundation of a new industrial relations system.

Tripartism is generally beneficial for trade unions because it guarantees inclusion of labor interests in the policymaking process. For Russian trade unions (such as the Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia, FNPR), this model was even more attractive because it legitimated their position in the new economic and political order. However, the effectiveness of the tripartite model was initially under question due to the principle contradiction between its neo-corporatist nature and the neoliberal scenario of economic reforms. The effectiveness of Western European neo-corporatism was based on well-functioning market mechanisms, developed trade unionism, and was closely linked to social democratic politics. None of these basic preconditions were present in the Russian context and remain absent today. Nevertheless, the government welcomed social partnership for a number of reasons. One was the fear of social protests as a reaction to economic liberalization and the inevitable drop in the living standards of the population. The government wanted to share responsibilities for the reforms with “social partners.” A no less important factor was the pressure from international financial institutions, such as the World Bank, IMF, and OECD, that wanted to ensure social peace in exchange for the financial support of economic reforms. The institutional transfer of the social partnership model was therefore driven by political, rather than economic reasons and resulted in so-called “illusory corporatism”2 and actual inefficiency of the tripartite institutions.

Tripartite Institutions in Russia: Low Policymaking Capacity

The establishment of the social partnership system began in the early nineties with the presidential decree “On Social Partnership and Conciliation of Labor Disputes” (1991) and the governmental decree “About the Russian Tripartite Commission on Regulation of Socio-Labor Relations” (1992). In 2002, the new Labor Code had finally solidified the new system of industrial relations based on a social partnership ideology. The SP system in Russia includes two vertical dimensions (territorial and industrial), eight levels of negotiations (federation, region, industrial branch/sector, territory, and enterprise), and seven types of social agreements depending on the number of partners (tripartite or bipartite) and the content of regulation (tariff agreements or general agreements). The main tripartite body at the federal level is the Russian Tripartite Commission for the Regulation of Social-Labor Relations (RTC), which includes 90 representatives of the partners and the government (30 from each party). The employers are represented by several national business associations, such as the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, Chamber of Commerce, and All-Russian Public Organization of Small and Medium-sized Businesses, and the top managers of the largest Russian companies. The employees side includes 27 representatives of the FNPR, which covers about 30 percent of Russia’s labor force, and three representatives of the so-called “alternative” or “free” unions that encompass about three percent of workers. Seven working groups within the framework of the tripartite commission negotiate issues in specified areas. The General Agreement between social partners provides basic principles of labor regulation at the federal level and is adopted by the RTC every second year.

While tripartite institutions look good on paper, in practice, they provide weak opportunities for trade unions to influence policymaking. The documents produced by the Commission have only a recommendary character. As an advisory body, the RTC can only provide consultations to federal state institutions regarding socio-economic policy and suggest amendments to federal and other normative acts. RTC decisions are not binding and vetoes cannot be overridden. General Agreements often have a declarative character that mostly demonstrates good intentions shared by the partners, rather than a plan of action or a compromise. Until recently, the work of the RTC was mostly reduced to approval of the documents that had already been adopted by the government.3 The domination of the state in policymaking creates an actual imbalance of power within the Russian Tripartite Commission, forcing unions and employers to fight for direct influence over the state instead of negotiating with each other.

During the 1990s, a number of laws and amendments were adopted to improve the work of the RTC (to convert it from “a club for the exchange of views”4 into a real policymaking body). However, the introduced changes had a superficial nature (such as, e.g., changes in the number of participants in the RTC or in the mechanisms of employers’ representation, etc.), while the low institutional status of the Commission remained intact. After 2000, the evolution of the SP system continued through the improvements of General Agreements. The agreements started increasingly focusing on more practical issues of socio-economic regulation, suggesting changes in the tariff system and the federal normative system of social planning.5 However, the non-obligatory character of the RTC decisions nullified these positive trends. For example, the 2008–2010 General Agreement suggested linking the level of the minimum wage guaranteed by the state to the minimum subsistence level as an urgent necessity. It was a rare case when an initiative of the trade unions achieved a consensus among the social parties. However, the provision has not been realized; currently, the minimum wage in Russia still constitutes about 55 percent of what is required for minimum subsistence.6 The inefficiency of the social partnership system forces trade unions to look for alternative ways to represent labor interests.

Direct Political Participation as an Alternative Mechanism for Labor Interest Representation

In European democracies, corporatist mechanisms of labor interest representation are often complemented by the political activities of trade unions. Trade unions use different electoral and lobbying strategies to gain direct access to the legislative process. In Russia, trade unions are not allowed to participate in elections; the Constitution of 1993 also deprived them of the right to introduce legislation directly to the State Duma. Hence, tripartite negotiations are the only legitimate option for them to participate in policymaking. Nevertheless, since the beginning of the 1990s trade unions have been successfully utilizing a wide range of electoral and lobbying tools, adapting them to the peculiarities of the political and economic context. During the period of political pluralism in the beginning of the 90s, the unions’ electoral strategies resembled “political party shopping” (Cook, 2007). Deprived of their rights of political initiative, labor unions aligned with any party ready to promote their interests in the Duma, including even ideological opponents such as the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, representing the main Russian industrial lobby and the biggest employer association. They allied with this group as part of the Civic Union political block in 1992. During the 1995 and 1999 State Duma elections, the FNPR created its own political bloc, the Union of Labor. Although unsuccessful in the 1995 electoral campaign, the Union of Labor, in alliance with the Fatherland (Otechestvo) party, won about 20 seats in the parliament during the 1999 elections. After the political centralization of the 2000s following Vladimir Putin’s rise to power and the drop in the number of parties competing for seats in the Duma, the unions’ main electoral strategy was concentrated on building an alliance with the ruling party “United Russia.” Union leader Andrey Isaev has become a leader of the United Russia Duma faction. Finally, after the political liberalization of 2012, trade unions converted “The Union of Labor” political movement into the “first laborist party in the history of Russian trade unions.”7

The evolution of the lobbying strategies of trade unions was similarly flexible. In the beginning of the 1990s, lobbying activities were mainly reduced to informal ties with individual deputies and bureaucrats in state executive bodies. After its success in the 1999 elections, FNPR created an informal inter-factional group “Solidarity” in the State Duma for building ties with representatives of different political factions; this institution has been reproduced in all subsequent parliaments. FNPR has been using every opportunity to extend its functional representation in legislative and governmental bodies via participation in various Duma committees, expert councils and commissions. The Vice-Chairman of FNPR Andrey Isaev has become a constant representative of the FNPR in the State Duma. In 1999, he was elected Vice Chair of the Duma Committee on Labor and Social Policy and Veteran Affairs and continued working as a Chair of that Committee in the fourth and the fifth Duma. In 2014, Isaev became a Vice-Chair of the State Duma, in 2016, he was elected the First Deputy Head of the United Russia faction for legislative activities.

Direct Political Participation as a Sustainable Institution

Electoral and lobbying mechanisms used by Russian trade unions today are well incorporated into state political and governance systems. The main electoral “locomotive” promoting FNPR representatives to the parliament is the ruling party United Russia (UR). In the 2016 elections, nine FNPR officials were elected to the State Duma as candidates from United Russia (four of them were elected on the basis of the federal party list, five are deputies from single-member districts). Another 18 representatives of FNPR promoted by UR were elected to regional parliaments. FNPR can also advance its representatives into legislative bodies on the non-party basis as a member of the Putin-made coalition “All-Russia People’s Front” (ONF). At the regional and local levels, some trade unions are active in building alliances with official opposition parties—Just Russia and Communists. Additionally, after the political liberalization of 2012, FNPR converted its former Union of Labor public movement into a political party that has branches in 53 regions. Although the party failed in the 2016 Duma elections, the FNPR Committee for Political Analysis and Action considers its preservation and further development as a complementary political tool.

The main lobbying instrument of FNPR in the State Duma is the informal interfactional group Solidarity. In the 2016 Duma, 18 deputies representing three parliamentary factions have already joined the Solidarity group. In spite of its informal status, the group has become a strong institutional lever allowing the FNPR to participate in legislative activity. The FNPR constantly works on strengthening its representation in the Committee on Labor and Social Policy and Veteran Affairs. Although Andrey Isaev is no longer the Chair of the Committee, the leadership positions of the First Vice-Chair and the Vice-Chair still belong to FNPR representatives. In recent years, FNPR has been extending its functional representation in the Duma and governmental bodies via participation in various expert councils and commissions. In 2012, the Rector of the St. Petersburg Humanitarian University of Trade Unions Aleksandr Zapesotsky became the Head of the newly created Expert Council for the Committee of Labor and Social Policy. In the new 2016 Duma, the Expert Council includes nine FNPR high-ranking officials. Another four FNPR officials represent trade unions in the Public Council by the Ministry of Labor that was created in 2013 to promote initiatives for optimization of the state social and labor policy. Although the decisions of the Council have only recommendatory character, it serves as an effective “access point” for trade unions to promote initiatives to the state executive bodies.

As in any authoritarian regime, building direct ties with the authoritarian ruler is the key political strategy. FNPR bet on Putin since his first election in 2000 and maintained its loyalty to him during Medvedev’s presidency. Trade unions served as one of the pillars of Putin’s electoral campaign in 2012 using their broad mobilization resources to draw support for the president during elections and organizing mass rallies to defend the president against the “white revolution” of 2011– 12. This loyalty paid off after Putin returned to power. Among his first decrees was one on the reconstruction of the Ministry of Labor, which was something the unions had demanded for over eight years, ever since the ministry’s liquidation in 2004.

Russian trade unions are not exceptional in terms of using informal ties to advance labor interest representation. In European countries, unions often resort to informal links to influence politicians and state officials. This phenomenon is referred to as the “gray power” of trade unions. With the spread of neo-liberalism undermining corporatist systems, trade unions in European countries increasingly resort to political levers, including informal links with political parties and state officials. However, in contrast to European countries where unions use “grey power” as a complementary political lever, in Russia the direct involvement of trade unions in politics and electoral activities are informal by definition. Political strategies are realized beyond official institutions of social partnership, and are based mainly on informal and inter-personal ties. The non-democratic nature of the Russian political environment results in a situation when trade unions ally not with socio-democratic political forces (as they do in European democracies), but just with the most powerful player on the political field, which is the ruling party and, even more important, with President Putin in person.

Social Partnership and Involvement in Politics as “Parallel” Institutions: The “Dual” System of Labor Interest Representation

The involvement of Russian trade unions in policymaking is realized today via two institutional mechanisms that comprise the “dual” system of labor interest representation. One of them is the formal neo-corporatist institution of social partnership, and the other is the informal institution of direct political involvement. These “parallel” institutions do not compete with each other, but rather complement each other to strengthen trade unions’ influence on policymaking. The institutions demonstrate different capacities for development due to the differences in their origins and character. The borrowed system of social partnership has only a limited ability to change because it was imposed “from above” with a politically and ideologically predetermined design. The institution of direct political participation, on the contrary, developed as a bottom-up process by adjusting to the challenges of the Russian political and economic context. The flexibility of the political institution was facilitated by its basically informal character, meaning that political participation was realized beyond official neo-corporatist institutions and strongly based on informal inter-personal networks.

The informal character of trade unions’ strategies makes it difficult to assess the actual influence of trade unions on policymaking. There are no empirical studies of the FNPR’s legislative efforts; the only source for analysis so far is official FNPR reports. However, comparing the two mechanisms of labor interest representation we can assume that Russian trade unions have achieved more influence in policymaking through informal political channels than via formal social partnership mechanisms. Since 2000, FNPR claims to have promoted over 300 amendments to the Labor Code due to its lobbying activity in the parliament. According to the Report to the IX Congress of FNPR in 2016, during the period of 2011–2015, FNPR specialists provided expertise on 374 draft laws, 68 of which became federal laws. Among other achievements in policymaking, the report mentions adoption of a federal law prohibiting agency labor and a number of laws improving pensions for the workers in the Far North. The list of “success stories” also includes blocking adoption of the liberal version of the Labor Code by the Solidarity group in 2000 and reestablishment of the Ministry of Labor in 2012.

While tripartism is the most desirable way for Russian trade unions to participate in policymaking, direct political involvement is a rather forced strategy. In the 90s, trade unions were involved in politics largely for their own institutional survival. The increasing use of political tools after 2000 was as a compensation for the inability of the neo-corporatist institutions to confront the growing liberal trends in the economy that the new Labor Code failed to improve. Today, Russian trade unions try to use their institutional capacity acquired through political channels to improve tripartite institutions of social partnership. In 2015, due to the FNPR’s lobbying initiatives, the government approved amendments to the law on the Russian Tripartite Commission, which strengthened its role in the development of legislative documents on labor and social issues. In particular, the amendments have made obligatory consideration of the bills by the RTC before their approval by the government, and participation of social partners in the government meetings addressing the issues of social and labor relations.

Overall, the “dual” system of labor interest representation in today’s Russia reflects specific features of the policymaking process in hybrid political regimes. Although formally the basic institutions of social partnership and direct political involvement resemble their analogues in Western democracies, they perform differently adapting to the peculiarities of the Russian political environment and market economy. The actual impact of trade unions on labor policy remains underestimated and requires further research.

Notes

1 This article was made possible thanks to support from the Centre of Excellence in Russian studies: Choices of Russian Modernization, Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki.

2 Ost, D. (2001) “Illusory corporatism: Tripartism in the service of Neoliberalism”, Politics and Society, Vol. 28, No. 4: 503–530.

3 Vinogradova E., Kozina I., Cook L.J. (2012) “Russian labor: Quiescence and conflict”, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3–4: 219–231.

4 Mikhail Shmakov, FNPR President, cited in Ashwin, S. and Clarke, S. (2003) Russian Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Transition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.: 148

5 Kozina, I. ed. (2009) Profsojuzy na predpriyatiyah sovremennoi Rossii: vozmozhnosti rebrendinga, Moskva.

6 Информационный сборник от VII к IX съезду ФНПР (2011–2015 гг.)

7 Информационный сборник от VII к IX съезду ФНПР (2011–2015 гг.)

Recommended Reading

- Ashwin, S. and Clarke, S. (2003) Russian Trade Unions and Industrial Relations in Transition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vinogradova E., Kozina I., Cook L.J. (2012) “Russian labor: Quiescence and conflict”, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3–4: 219–231.

- Olimpieva, I., Orttung, R. (2013) “Russian unions as political actors” Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 60, No. 5: 3–16

About the Author

Irinia Olimpieva is a research fellow and the Head of the research stream “Social Studies of the Economy” at the Center for Independent Social Research in St. Petersburg.

Statistics

Labor Protests in Russia

All the figures below come from the Center for Social and Labor Rights (CSLR) in Moscow. CSLR is a Russian nonprofit NGO devoted to the promotion of, compliance with and protection of social and labor rights.

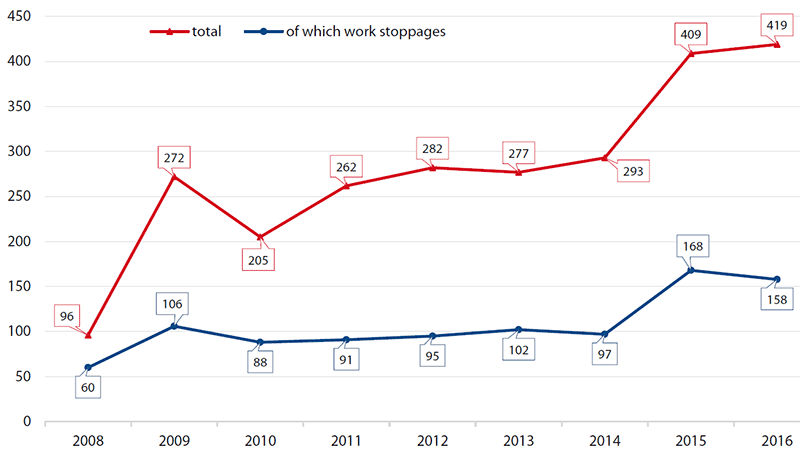

Figure 1: Total Number of Labor Protest Actions 2008–2016

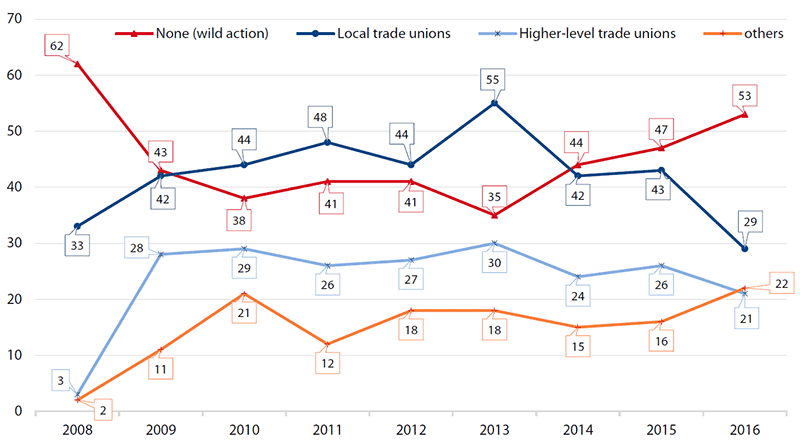

Figure 2: Organizers of Labour Protest Actions 2008–2016 (share in total number of protests)

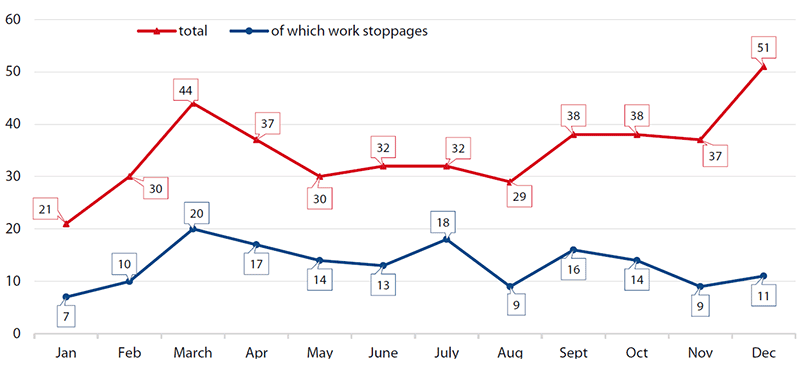

Figure 3: Total Number of Labor Protest Actions in 2016

Russian Trade Unions in International Comparison

The following figures come from the International Labour Organisation ILOSTAT—Industrial relations. The only tripartite U.N. agency, the ILO brings together governments, employers and worker representatives of 187 member States, to set labor standards, develop policies and devise programmes promoting decent work for all women and men.

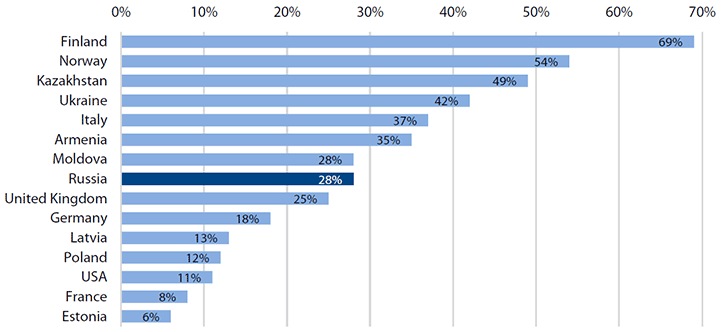

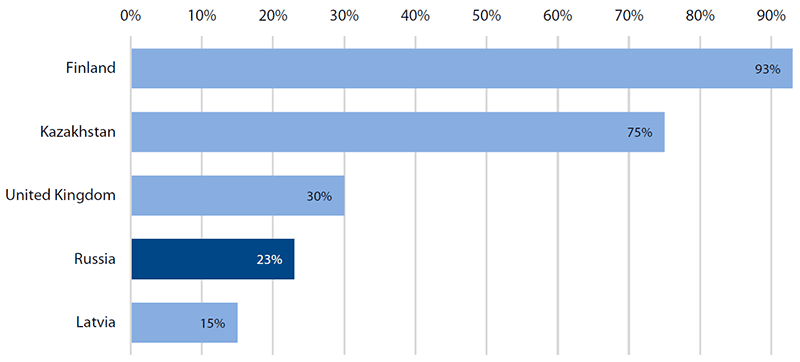

Figure 1: Trade Union Density in International Comparison (2012/13)

Figure 2: Collective Bargaining Coverage in International Comparison (2012/13)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.