One Belt, One Road: China´s Vision of ´Connectivity´

20 Oct 2017

By Stephen Aris for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy (No. 195) was originally published in September 2016 by the Center for Security Studies. It is also available in German and French.

President Xi Jinping has outlined plans to construct huge infrastructural links to better connect China with the rest of the world. This strategic vision of a “New Silk Road” is now more often referred to as the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) initiative. Beijing is allocating huge amounts of finance to the project, but China’s neighbors remain wary of OBOR’s geopolitical implications.

Since becoming China’s “paramount leader” in 2013, Xi Jinping has launched a series of both domestic and foreign policy initiatives. All of these aim to ensure political stability and continued economic growth at home and to position China as a new major player within international affairs. What is noticeable about Xi’s various policy initiatives is that they draw an increasingly overt link between domestic and foreign affairs. Arguably, the most noteworthy in this regard is the “New Silk Road” strategic vision, now more often referred to as the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) initiative.

Invoking the historical imagery of the ancient Silk Road, OBOR envisions the construction of a set of grandiose infrastructural links that run from China to the rest of the world. The aim is to generate greater trade and enhance connectivity between China and Africa, Eurasia, Europe, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. While a few sections of the New Silk Road are already in place or under construction, currently most only exist on the drawing board. Nonetheless, this vision of connectivity is beginning to catch the attention of the international community. Governments, businesses, and citizens that may lie along the proposed routes are attracted by the huge amount of finance that Beijing has suggested will be allocated and raised to make the vision a reality. At the same time, they are also wary of the geopolitical implications of becoming a node in these China-orientated routes of connectivity.

Due to its free trade agreement with China and its growing role as an “offshore renminbi hub”, Switzerland is well placed to play an important role in engagement with OBOR in the European context.

OBOR: What Do We Know?

Six months after becoming president in 2013, Xi Jinping undertook a diplomatic tour of four of the five post-Soviet republics of Central Asia. During his visit to Kazakhstan, Xi gave a speech setting out a “strategic vision” to construct a “New Silk Road”. Drawing heavily on historical imagery of the 2,000-year-old Silk Road that ran from China to Europe through Central Asia, he proposed the creation of a (land-based) economic belt “to open up the transportation channel from the Pacific to the Baltic Sea”. Less than a month later, during a visit to Indonesia, Xi outlined the intention to build a “Maritime Silk Road” that would run from China to the Indian Ocean (and from there, link to South Asia and Southern Africa) via Southeast Asia. These two speeches, then, set out a wider policy vision of infrastructure-building and connectivity with China at its apex.

“Visions and Actions”: OBOR routes

Xi’s speeches were, however, rather vague on details. Therefore, over the next few years, Beijing set about encouraging China’s political institutions, provincial governments, business community, think tanks, and scholars to fill in the blanks. What has emerged is a series of more or less concrete plans, as well as a more sophisticated elaboration of the basic concept underlying the vision. In the process, a number of other key Chinese foreign-policy concepts have been tied together around an argument that increased “connectivity” is the recipe for international development and stability. In this way, the Economic Belt and the Maritime Road are presented as a mechanism by which other countries and regions can benefit from the gains of China’s “Harmonious Rise”, by engaging in “win-win” cooperation.

A Belt and a Road – To Where?

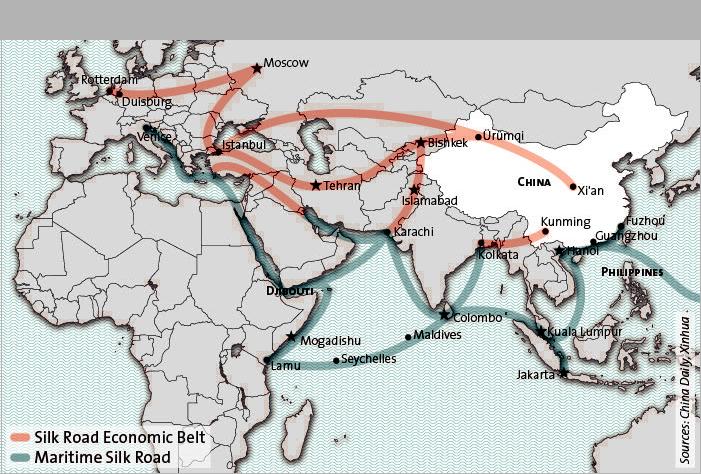

Due to the vagueness of the notions of a continental “Economic Belt” and “Maritime Silk Road”, there has been great speculation about their exact paths of travel. Initially, the Xinhua News Agency published a map showing two route lines, which caused much discussion. However, this map should not be taken too seriously, as illustrated by the 2015 joint declaration by Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin outlining their intention to coordinate the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union with the Chinese “economic belt” – Russia is bypassed in the routes marked on the Xinhua map. More instructive is the publication last year of an official framing document entitled “Visions and Actions” (see map), which suggests that five general routes (three by land and two by sea) are currently being considered. These differentiated routes are expressive of the growing trend to reclassify projects already completed, underway, or agreed prior to Xi’s 2013 speeches under the heading of OBOR. Examples include the Chongqing-Duisburg railway, the Khorgos Special Economic Zone, and the long-discussed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

At the same time, the “Visions and Actions” document should not lead to the conclusion that Beijing has fixed notions about routes and participating partners. These suggested pathways serve more as broad organizing notions, around which a range of bilateral and multilateral cooperative activity with a variety of partners may be orientated. From this perspective, OBOR represents a diplomatic space in which to consolidate established cooperative relations and open opportunities for forging new ones. In this sense, Beijing is fully aware that all OBOR routes are ultimately dependent on the reciprocal engagement of partners. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that without the active commercial participation of both Chinese and foreign companies in public-private or simply private ventures, OBOR will not come to fruition. As such, the metaphorical framing of OBOR would appear to be as significant as the concrete projects that may follow. Indeed, OBOR’s success will not only be judged by Beijing on whether a single continuous route is established from Xi’an to Berlin or from Shanghai to Nairobi. It will be deemed useful if it facilitates a general increase in “win-win” cooperative relations that benefit their wider aims: domestic economic growth; a more prominent role in the world; and acceptance of a distinctly Chinese notion of international relations and development.

How Will It Be Built?

Away from its symbolic importance for framing Chinese foreign policy, the other main questions being asked about OBOR are: How will it be built, and who will be picking up the bill? To get the ball rolling, the Chinese state is laying down a substantial financial seed fund (see text box ‘The Funding of OBOR’). In doing so, Beijing is pursuing an associated foreign policy goal of establishing an alternative set of (Chinese-orientated) global financial institutions to the prevailing US-centric ones – namely, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. As well as ensuring China a seat at the top table of international politics, these moves are also aimed at establishing the renminbi as a major international exchange currency.

However, the scale of OBOR is such that Chinese state finance and construction capacity alone is not even close to being sufficient. OBOR is thus premised on complementary investments and active participation from those Chinese provincial governments and companies most likely to benefit from greater connectivity. Furthermore, China expects that foreign partners – state and private – along the Belt and Road should contribute both financially and to the process of constructing and maintaining this infrastructure. Of course, these expectations vary depending on the capacity of the partner in question. In cases in which the host country for OBOR projects can contribute little, China – in return for covering all of the costs and risks – expects to receive greater direct control over these projects and the domestic policies associated to them. In such countries, there are domestic debates about whether the risks of losing sovereign control and be-coming overly dependent on China are worth the undoubted windfall of large-scale Chinese investment in the development of national infrastructure. Such tension often manifests itself within the frame of elite-society conflicts of interests. For example, in April 2016, Kazakhstan saw several days of protest against a political decision to extend a law allowing foreigners to lease agricultural land, with the expectation that it was designed to allow Chinese companies to do exactly that. The perception among the wider Kazakhstani population is that China’s investments have given Beijing undue influence over the Nazarbayev government. While the political elite are happy to accept such loans and investments, many ordinary citizens have concerns that this leads to a loss of national sovereignty and jobs, as well as about how Chinese companies treat Kazakh workers. Similar tensions are evident in other countries that lie along the Belt and the Road.

Why Is China Building OBOR?

Analysts have suggested various rationales for why Xi’s China is pursuing OBOR: Commentators on China often emphasize the connection between Beijing’s concerns about economic growth and political stability. As one of the few remaining Communist governments in the world, and having been strongly influenced by the collapse of the USSR, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is concerned with ensuring political and regime stability by delivering continual strong economic growth. They are wagering that as long as economic conditions improve, any protests are unlikely to find enough support to represent a tangible challenge to one-party rule. From this standpoint, OBOR may be seen as a strategy to safeguard economic growth and expansion in the short to medium term while the Chinese economy undergoes a period of transition from a low-value export model to a model based on domestic consumption and higher-value exports.

To bridge this transition, China needs to ensure secure energy supply routes and open up new market opportunities for both its established low-value and its increasing volume of high-value goods. OBOR could potentially deliver both. It could reinforce established partnerships and build new ones with energy exporters in Central Asia the Middle East, and Africa. While, as stated in the 2015 government framing document, the Belt and Road aim to connect “the vibrant East Asia economic circle at one end and developed European economic circle at the other”. It is hoped that this will develop new markets for China’s increasingly diversified production, allowing Chinese companies to keep expanding even while domestic demand slows and is reoriented towards middle-class consumerism. This could be achieved by reducing transportation costs and potentially lowering tariffs, paving the way for Chinese goods to make a more competitive entry into these foreign markets.

Alternatively, OBOR can also be viewed as simply an update of a previous policy strategy: the “Go West” strategy. This strategy, pursued in the 2000s, sought to better connect China’s western provinces to the “economic miracle” taking place on its eastern seaboard. In the process, it was hoped that this would alleviate the ongoing security threats emanating from the Uyghur Xinjiang Province. In this context, OBOR is simply an extension of this strategy, which seeks to connect Xinjiang not only with the rest of China, but also to the nation states on its western borders and beyond. The hope is that this may deliver economic improvements to the region, including for non-Han populations, thereby, incentivizing them to prioritize the maintenance of stable connectivity over political challenges to the CCP’s regional policies and the validity of Chinese sovereignty over the region as such.

The Funding of OBOR

Silk Road Fund (est. US$40 bn)

- Created expressly to fund OBOR projects

- Funded by various state Chinese institutions (using amassed currency reserves)

Loans from China’s policy banks – China Development Bank, China Export-Import Bank (lent US$80bn in 2015), China Agricultural Development Bank

- Likely largest source of capital for OBOR projects

Asian Infrastructural Investment Bank (AIIB) (est. US$100 bn)

- Created as an alternative, but complementary Multilateral Development Bank (MDB) to the World Bank, specifically for funding infrastructural projects in Asia

- 37 Regional and 20 Non-Regional Members. Switzerland, Germany, France, and UK among non-regional members

- China contributes US$30bn, rest from other members

BRICS New Development Bank (est. US$100 bn)

- Created as an MDB to fund infrastructure projects in developing countries

- five BRICS states have equal vote on board

- US$50 billion underwritten in equal share by each member state

Investments by Chinese provincial governments and banks

OBOR is also said to be driven by wider foreign policy goals. Under Xi, China no longer seems so intent upon downplaying its global status and insisting it remains a “developing” nation, albeit the natural leader of the “developing” world. Beijing now seems to be positioning itself as one of the most influential actors on the international stage. To this end, OBOR is important in elaborating Beijing’s view on what the future international order should look like and how it should be governed. This view is by no means a direct challenge to the existing international order, but it does envision alternative and parallel structures that are centered on China. These arrangements also work towards establishing a regional leadership position, especially in East Asia, and in response to projects such as the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Furthermore, some analysts see OBOR as a means of advancing China’s regional geo-political and security interests. In this view, the land belt is to enhance Beijing’s geopolitical influence over regions in which it has traditionally been peripheral, including Europe. Simultaneously, the maritime road would serve to secure vital shipping supply lines, magnify China’s strategic leverage over the other claimants in the on-going territorial disputes in the East and South China Sea, and advance military interests in the Indian Ocean in a manner akin to the “string of pearls” thesis – which originated in a 2005 report to the US Congress by a consulting firm – that suggests China is building-up its control of strategic sea lanes in the Indian Ocean region.

Switzerland and OBOR

As the only continental European country that has a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with China, Switzerland holds an important strategic position in terms of China-EU dialog about the development of OBOR. For Beijing, the China-Switzerland FTA is an example that it hopes will lead in the long run to a similar agreement with the EU, driven by cooperation on OBOR.

Furthermore, Switzerland may become a major international “offshore renminbi (RMB) hub”. As a result, Switzerland could have a significant facilitating role for OBOR-related economic transactions in RMB between China and other European countries.

Therefore, Switzerland is well placed to be both a symbolic and financial bridge between China and the EU, and, thus, to shape certain aspects of OBOR in Europe.

These geopolitical aims are also an outlet for another consequence of China’s “economic miracle”: the amassing of huge currency reserves. One viewpoint is that holding on to these currency reserves is not of much strategic or economic benefit. As a result, Chinese policymakers are said to have been searching for a way to make productive use of these reserves to support the nation’s wider geopolitical interests. In using them to support OBOR, the government is putting this accrued monetary clout to good use by further enhancing China’s role as a major political and development player on the international stage.

Each of these rationales on its own would plausibly explain the motivations behind OBOR. Hence, in practice, OBOR is best interpreted as a policy tool aimed at achieving many ends that overlap domestic and foreign affairs at one and the same time.

A Land Bridge to Europe?

The notion of “connectivity” at the heart of the OBOR vision is primarily about connecting China to Europe, especially via the land-based economic belt. The emphasis on the China-Europe land bridge is evident by the fact that there are already several completed projects in this direction, such as the Chongqing-Duisburg railway line. The aim is to dramatically cut the time it takes by ship to transport goods between China and Europe. Against this back-ground, European countries and the EU are currently seeking to formulate their policy response to OBOR.

There are significant potential economic benefits to participating in the establishment of such infrastructure links to connect the flows of goods between Europe and China. It would facilitate greater and easier access to a huge market for European producers. Nevertheless, China has yet to make a completely convincing case to its prospective European partners, who ponder how exactly they will benefit from OBOR. This is in part due to the clear disparity in China-European trade. China provides Europe with an array of low-value goods while, in return, Europe sells mainly high-value goods and services to China. This distinction in the type of trade flows is also evident in the traffic between the two markets – currently, the Chongqing-Duisburg train arrives from China packed full with low-value goods, but because European exports to China are not mass-and volume-intensive, it makes the return journey largely empty. Trade coordination is further complicated by the failure to agree a EU-China Free Trade Agreement, with continued tariff barriers mitigating the potential cost-saving advantages of the quicker-speed of the land route.

Adding to the concerns about trade imbalances, the most viable OBOR land route is geopolitically problematic from an EU perspective. Last year’s joint Russian-Chinese declaration about coordinating the EEU and OBOR increases the likelihood that many routes in the economic belt could go through Russia. This prospect is reinforced by the security situation in many of the states along the alternative southern route that would bypass Russia. With the EU-Russia relationship at an all-time low, and OBOR potentially bringing to the fore the contested question of Ukraine’s role as a transit state between Russia/EEU and the EU, then China-Europe land connectivity begins to look like a geopolitical hazard from the European perspective.

Irrespective of these concerns, China has already made moves to boost support for OBOR among the EU’s member states. The 2015 EU-China summit incorporated OBOR into its agenda for ongoing dialog and cooperation. In addition, in 2012, China created the 16+1(China) forum to enable Beijing to engage directly with Central and East European states, including some EU members. In this forum, China can sell the merits of OBOR to specific EU member states, who may see the potential benefits of a Silk Road economic belt running through their territory to connect the economic powerhouses of China and Western Europe. They, then, could become advocates for engaging OBOR within the EU. Indeed, last year, Hungary became the first EU member state to sign a bilateral memorandum out-lining a mutual interest and cause in implementing OBOR. China is financing and constructing a new high-speed railway between Budapest and Belgrade, with further plans to extend this railway link to the Greek port of Piraeus, which has also seen significant Chinese investment. This cooperation is not something that other EU members should be too suspicious or concerned about. It does, however, point to the need for a full and active debate about how Europe should respond to OBOR. It also indicates that it would be advantageous for the Europeans to have their voices heard in the formative phase of its development. To this end, the most effective way for all European states to amplify their voice vis-à-vis OBOR is to coordinate their stances with one another.

Further Reading

Nadine Godehardt, “external pageNo End of History. A Chinese Alternative Concept of International Order?call_made”, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) Research Paper (January 2016).

Nicola Casarini, “external pageIs Europe to Benefit from China’s Belt and Road Initiative?call_made”, Istituto Affari Internazionali Working Paper (October 2015).

Gisela Grieger, “external pageOne Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s regional integration initiativecall_made”, European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing Paper (July 2016).

Most recent issues in the ‘CSS Analyses in Security Policy’:

- Why Security Sector Reform has to be Negotiated No. 194

- Libya – in the Eye of the Storm No. 193

- Transatlantic Energy Security: On Different Pathways? No. 192

- Peace and Violence in Colombia No. 191

- Bosnia: Standstill despite New Strategic Significance No. 190

- Nordic Security: Moving towards NATO? No. 189

About the Author

Dr Stephen Aris is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zürich. He is the co-editor of “The Regional Dimensions of Security” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) and “Regional Organisations and Security” (Routledge, 2013).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.