Russian Analytical Digest No 228: Cultural Politics

18 Dec 2018

By Ulrich Schmid, Peter Rollberg and Andey Makarychev for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 30 November 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru (external pageCC BY 4.0call_made)

Kirill Serebrennikov and the Changing Russian Politics of Culture

By Ulrich Schmid, University of St. Gallen

Abstract

The house arrest of the acclaimed theatre and cinema director Kirill Serebrennikov provoked a wave of protest and solidarity among Russian as well as foreign artists. Serebrennikov is accused of embezzlement and misallocation of state funds. To be sure, irregular accounting practices at theaters throughout Russia are quite common; yet, Serebrennikov credibly denies any personal misconduct. The Serebrennikov case illustrates most aptly the volatility of Russian cultural politics over the last ten years.

Once Strong Connections to the State

Kirill Serebrennikov (born 1969) is a maverick in theRussian theater scene. His unorthodox education places him outside existing traditional structures. Serebrennikov staged amateur spectacles already in high school, and later-on during his education in physics at the University of Rostov-on-Don. At the same time, he began to work as a film director. In 2000, he moved from his native Rostov to Moscow. Here, he successfully staged contemporary plays by Vassily Sigarev (born 1977) and the brothers Presnyakov (Oleg, born 1969, and Mikhail, born 1974). He was soon reputed to be the most innovative theater director in Russia.

The government kept an eye on him as well. Vladislav Surkov, the “grey cardinal” of the Kremlin, was highly impressed with Serebrennikov’s achievements. Surkov held a nominally modest governmental post, serving as the deputy chief of the presidential administration. His main task consisted of raising acceptance for Putin’s rule among the younger, urban generation. He coined the term “sovereign democracy”, and developed an ambitious project to turn Russia into a modern, efficient, and attractive state. To achieve this objective, he initiated a dialogue with leading rock bands in2005.1 Surkov controlled large funds for cultural projects and eventually decided to involve Serebrennikov in his activities. In 2011, Serebrennikov was offered the leadership of a large state project under the title “Platforma”.The main goal of “Platforma” consisted of developing and disseminating contemporary art. Four branches were established: dance, music, theater, and multimedia. “Platforma” organized and staged 320 events between2011 and 2014. In 2012, Serebrennikov was promoted to artistic director of the Gogol Center in Moscow. Not without noise and protests from the former ensemble of actors, he turned the Gogol Center into one of the hotbeds of contemporary dramaturgy. Surkov’s injection of state funds considerably facilitated Serebrennikov’s rise to fame. At the same time, Surkov’s personal vanity played a role in his backing of Serebrennikov. In2011, Serebrennikov agreed to stage Surkov’s own controversial novel Near Zero in one of Moscow’s theaters. During the political protests in the winter 2011/2012in Moscow, Surkov temporarily fell from grace and was removed from his position. Of course, Serebrennikov knew he was treading on thin ice. Nevertheless, he continued to collaborate with the state in the field of cultural production. In a column for the September 2014Russian Esquire, he confessed: “We have to visit every government and to initiate talks. We have to say: Government, listen, I know that you are mendacious and selfish, but you have to support the theater and art by virtue of the law, so please fulfill your obligations. For the sake of theater, I am not ashamed to do so.” 2

This ambivalent attitude towards the state proved to have painful consequences for Serebrennikov. Close relations with the authorities worked fine during Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency, but turned disastrous during President Putin’s third term in office. While Medvedev championed the slogan of “modernization” for Russia, Putin changed the political leitmotif to “securitization”.

By 2012, Serebrennikov’s cinematographic and theatrical art was no longer deemed “innovative” or “daring”, but an undesirable expression of a decadent, post-modernist, global, and therefore “un-Russian” aesthetic. The Russian ministry of culture played an important role in this shift towards conservatism. Immediately following his inauguration in May 2012, President Putin appointed the conservative historian Vladimir Medinsky as minister of culture. Medinsky pursues an unabashedly nationalistic course in his approach to the arts. In his 2011 doctoral dissertation, Medinsky dealt with the allegedly false or condescending representations of Russia by Western historiographers. In the preface to his dissertation, he scandalously stated “the national interests of Russia” create an “absolute standard for the truth and reliability of the historical work.”3

Medinsky also presides over the Russian Association for Military History, which turned into one of the most active players in the patriotic reshaping of the public space since its foundation in 2013. Medinsky understands culture as an “integral part of the Russian national security strategy” and openly advocates conservative tastes. The official document “Foundations of the cultural policy of the Russian Federation” from 2015 highlights the principle of the freedom of artistic creativity. However, the document continues, the state should not blindly support every creative effort: “No formal experiment may justify the production of content that is at odds with the traditional values of our society or the absence of any content at all.”4

The Taboo of Homosexuality

Apart from this shift in the official cultural policy, homosexuality became an important zone of conflict between the state and the artist. Serebrennikov is openly gay and does not bother to hide his sexual orientation, including frequently wearing extravagant outfits. In 2012, he planned a biopic about Piotr Tchaikovsky who struggled his entire life with his homosexuality. Serebrennikov planned to address this strain, but the minister of culture Medinsky opposed the plan and maintained that Tschaikovsky’s music had nothing in common with his private life. After this falling out, Serebrennikov returned a first installment of a governmental grant, and announced that he would look for sponsors abroad.5 In 2013, the Russian debate around homosexuality acquired a legal dimension. The Duma passed a bill that prohibits the propaganda of homosexuality among minors. This new law practically banned the topic of homosexuality from the Russian public sphere. Nevertheless, Serebrennikov continued to present artistic elaborations of homosexuality in his works, most notably in his ballet “Nureyev”(2017). The premiere of the show was postponed by half a year because the production was allegedly not yet ready. The true reason was, of course, the ongoing investigation in the Sererbrennikov case. Ironically enough, prominent members of the cultural establishment, including Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov and the general director of the influential First Channel of Russian TV Konstantin Ernst, eventually showed up at the premiere and admittedly enjoyed the ballet.

Images of the Soviet Past

An additionally significant shift took place with the official image of the Soviet Union. In his famous “Millennium Manifesto” from 1999, Putin had presented a grim view of Russia’s Soviet past: “Communism and the power of Soviets did not make Russia a prosperous country with a dynamically developing society and free people. […] It was a road to a blind alley, which is far away from the mainstream of civilization.”6 Around the end of the first decade of the 2000’s, a slow but steady rehabilitation of the Soviet Union began. Even Stalin was given credit for “effectively managing the country”. Putin’s administration turned the 60th anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany into a spectacle for the masses in 2005. In 2009, the Moscow station “Kurskaya” was renovated and, without much ado, Stalin’s name reappeared in full readability on the stone pillars. To be sure, Putin observed a cautious distance towards the bloody tyrant until 2015. And yet, in his interviews with Oliver Stone, Putin spoke about Stalin and compared him to Western dictators like Napoleon or Cromwell. He pointed to the public veneration of these figures in France and Britain, and warned against the demonization of Stalin that led to the rise of Russophobe sentiments in the West.

The newest chapter in the positive assessment of the Soviet past is the controversy about Solzhenitsyn’s100th birthday in December 2018 (see related article in this issue of the RAD). In 2000 and 2007, Putin had courted Solzhenitsyn and paid him personal visits in his Moscow flat. Already in 2014, Putin signed a decree ordering preparations for celebrating Solzhenitsyn’s birthday. By now, the enthusiasm has shrunk considerably. The main reason for this shifting attitude is the reassessment of Solzhenitsyn’s exile in the USA, and his relentless fight against the Soviet government. For the Kremlin’s current perspective, the Soviet Union serves as an incarnation of the 1000-year-old tradition of Russian statehood, however imperfect it may have been. Serebrennikov’s latest film “Summer” about the Rock legend Viktor Tsoi (1962–1990) is guilty of the same sin. Set in expressive black and white, this movie insinuates that real artistic life in the Soviet Union was only possible in the underground, far away from any state structures.

Yevgeny Fyodorov: Instigator of the Serebrennikov Case

It would be too simplistic to see the persecution of Serebrennikov as the sole reaction of an increasingly repressive state against artistic provocations. As such, it seems rather improbable that the center of Russia’s political power ordered the attacks on Serebrennikov. The relatively mild punishment, consisting of house arrest, indicates special treatment for the famous director. By contrast, the former minister of economic development Aleksei Uliukaev was swiftly sentenced to eight years in a labor camp and a fine of 130 million rubles in a similar case of alleged embezzlement. The main difference between Uliukaev and Serebrennikov lies in who stands behind the legal actions against them. Igor Sechin, the almighty head of Rosneft and Putin’s close ally is likely behind the Uliukaiev case, whereas the ultra-conservative deputy of the Duma Yevgeny Fyodorov pulls the strings in Serebrennikov’s confinement. Fyodorov is the infamous founder of the patriotic “National Liberation Movement” who seeks for Russia to regain its “cultural sovereignty”. This claim is mainly directed against Western popular culture. Against this background, it comes as no surprise that it was Fyodorov who asked the Investigative Committee to look into the financial details of Serebrennikov’s Gogol Center in 2013. Sechin probably acted at least with the tacit approval of the Kremlin. Fyodorov’s case is different. He belongs to the enthusiastic followers of Putin’s aggressive turn in both his domestic and international politics since 2012. These enthusiasts may pose a problem for the Kremlin who may perceive their radical claims a nuisance over time. Another case in point would be the former Crimean state attorney Natalia Poklonskaia, who is now a hardliner among the deputies from “United Russia” in the Duma. In two incidents, Poklonskaia overtook the patriotic Kremlin on the right: After Putin’s public debunking of Lenin, she compared Lenin to Hitler. Moreover, she heavily criticized the historical film “Matilda” (2017), which narrates the romance between future Tsar Nicholas II and a Polish ballerina. To be sure, both the film and the director are fully in line with the official patriotic culture of politics: The Tsar eventually leaves his concubine for the throne, and the director joined an open letter signed by more than 500 loyal intellectuals in support of Putin’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014.

Both Fyodorov and Poklonskaya are ambivalent phenomena for the Kremlin. On the one hand, the Kremlin is embarrassed by such radical positions, but at the same time it may not discipline its most fervent supporters too harshly. On the other hand, people like Fyodorov and Poklonskaya allow the Kremlin to present itself as a moderate player in the field of Russian culture. In contrast with the claims of extreme nationalists, the general public will perceive the Ministry of Culture as taking a “middle ground”. In a certain sense, Peskov’s and Ernst’s presence at the premiere of the “Nureyev” ballet may symbolize a mild reprimand of cultural extremists like Fyodorov.

As usual in such cases, President Putin distanced himself from the investigations against Serebrennikov. In May 2017, he commented on the razzia in the Gogol Center with the phrase “Idiots”. Later, he explained that the Serebrennikov affair was exclusively a criminal case without political implications. During a meeting of the “Council on Culture and the Arts” in December 2017,he called the investigation against Serebrennikov not “a persecution, but a prosecution”. At the same time, he proposed to draft a new law on culture, indicating the rising importance of culture in the political design of the Russian Federation.7

Notes

1 David-Emil Wickström, Yngvar B. Steinholt, Visions of the (Holy) Motherland in Contemporary Russian Popular Music: Nostalgia, Patriotism, Religion and Russkii Rok. In: Popular Music and Society 32 (2009), 313–330, S. 321.

2 Pravila zhizni Kirilla Serebrennikova. In: Esquire (24 Sept. 2014). <external pageesquire.ru/rules/5886-serebrennikov/>call_made

3 V.R. Medinsky: Problemy ob-ektivnosti v osveshchenii rossiiskoi istorii vtoroi poloviny XV–XVII vv. Moskva 2011 <.dissercat.com/content/problemy-obektivnosti-v-osveshchenii-rossiiskoi-istorii-vtoroi-poloviny-xv-xvii-vv>

4 Osnovy gosudarstvennoj kul'turnoi politiki. Moskva 2015, 3, 28. <mkrf.ru/upload/mkrf/mkdocs2016/OSNOVI-PRINT.NEW.indd.pdf>

5 Ulrich Schmid: Technologien der Seele. Vom Verfertigen der Wahrheit in der russischen Gegenwartskultur. Berlin 2015, 351f.

6 Vladimir Putin: Russia at the Turn of the Millenium. In: Richard Sakwa: Putin. Russia’s Choice. London 2008, 317–328.

7 Putin o dele Serebrennikova. Eto ne presledovanie, a rassledovanie. (21.12.2017). <ntv.ru/novosti/1963885/>

About the Author

Ulrich Schmid is a Professor of Russian Culture and Society at the University of St. Gallen.

Russian Public Opinion About the Case of Kirill Serebrennikov

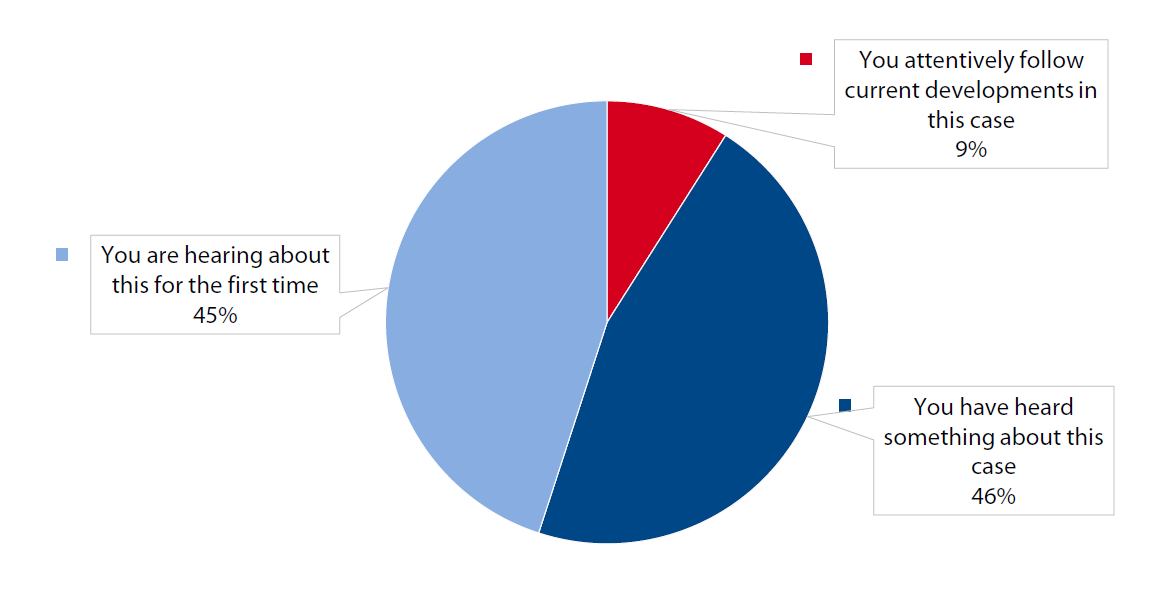

Figure 1: Have You Heard That Kirill Serebrennikov, Director and Artistic Administrator of the Theater “Gogol-Tsentr”, Was Arrested and Placed Under House Arrest?

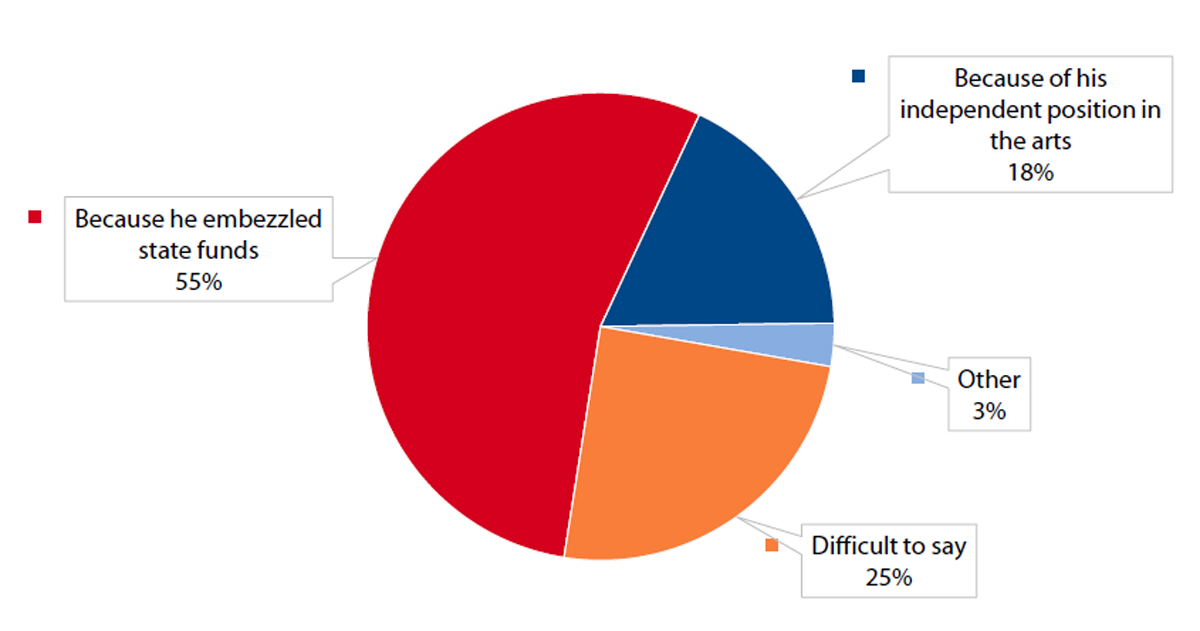

Figure 2: In Your Opinion, Why Were Criminal Charges Actually Brought Against Kirill Serebrennikov? (this question was posed only to respondents who answered “You attentively follow current developments in this case” and “You have heard something about this case”)

Solzhenitsyn’s Embattled Legacy

By Peter Rollberg, George Washington University

Abstract:

Russian president Vladimir Putin’s praise for Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn raised eyebrows; Solzhenitsyn’s public agreement with Putin’s domestic and foreign policy caused widespread dismay. Despite strong opposition, Russia’s establishment has remained firm in its endorsement of the Nobel laureate’s literary and political legacy. Ten years after his passing, Solzhenitsyn has become a useful authority legitimizing Putin’s statist agenda.

Remembering Solzhenitsyn

The government of the Russian Federation has declared 2018 the “Year of Solzhenitsyn.” In August, numerous cultural events were dedicated to the 10th anniversary of the writer’s death, and many more are to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth on December 11, including several documentaries produced for these occasions and already screened on TV. At the Bolshoi Theater, the opera One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Tchaikovsky will premiere; Vladimir Spivakov’s “Soloists of Moscow” will perform Solzhenitsyn’s “Russia’s Prayer,” set to music by Yuri Falik; as part of that concert, Ignat Solzhenitsyn, the writer’s son, will play one of Beethoven’s piano concertos. The Central Academic Theater of the Russian Army is putting on a dramatization of Solzhenitsyn’s epic The Red Wheel. Rostov-on-Don, where the writer grew up, will hold a documentary and feature film festival, and students at the local university have created a virtual Solzhenitsyn museum. Natalya Dmitrievna, Solzhenitsyn’s widow, tirelessly acts as the authorized spokesperson for her late husband, enjoying the status of a premier celebrity in Russian society.

Not everybody is celebrating, however.

Will the Real Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Please Stand Up?

During an election forum with one of the candidates for mayor of Moscow, several participants asked that the planned construction of a Solzhenitsyn monument in central Moscow be halted. The Solzhenitsyn monument in Vladivostok, the city from whence the writer’s return from exile began in 1994, is regularly vandalized by hanging a cardboard placard with the inscription “Judas” around the sculpture’s neck. While newspapers such as the official Rossiiskaya Gazeta celebrate Solzhenitsyn’s legacy as a writer and political thinker, other publications point to the government’s hypocrisy in embracing one prominent victim of Stalinism while persecuting Memorial and other efforts to keep the memory of communist oppression alive.

In current Russian discourses, Solzhenitsyn is interpreted and quoted with deliberate selectiveness, causing widespread confusion about the writer’s real positions. Was he a Russia-hater (“Russophobe”) or an ethnic nationalist? Did he side with the West or yearn for a strong Russian state, beyond his militant anti-Soviet rhetoric? And was he a genuine literary genius— a legitimate heir to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky— or a mediocre megalomaniac whose verbose narratives have negligible aesthetic value? The spectrum of responses is wide and multifaceted. Remarkably, opinions are not always in sync with the political positions of those voicing them.

At no time did Solzhenitsyn’s star shine brighter than in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970 and being forcibly expelled from his homeland in 1974 transformed the erstwhile math teacher into a writer-cum-martyr, revered as an international moral and political institution. His works enjoyed an unparalleled status in academia and were debated not only by Slavic specialists, but also by historians and political scientists, while his statements about global issues were eagerly quoted by the international mass media and feared by Soviet watchdogs. This hype ended when it became obvious that Solzhenitsyn was far from advocating Western values. His Harvard graduation speech in June 1978 signaled that this victim of totalitarianism was not a liberal democrat at all. The question of what exactly he was became the topic of intense discussions, with labels ranging from “fascist” to “saint.” Then, safely self-isolated from U.S. society (which he never understood nor cared to study), Solzhenitsyn fell into oblivion. By the mid-1980s, the recluse from Vermont had lost most of his influence.

In hindsight, Solzhenitsyn’s main accomplishment was the permanent damage he inflicted on the image of communism. After One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, The First Circle, and especially The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet communism was forever associated with its gigantic network of concentration camps. Just as the writer had predicted in his autobiographical The Oak and the Calf, one man managed to discredit an entire empire and the ideology sustaining it.

A Star Reborn

Solzhenitsyn’s return to Russia in 1994, rendered with effective mise-en-scene, was intended to establish him as a permanent institution in the post-Soviet nation. That strategy failed miserably. The writer’s personal television show was cancelled in September 1995 after only five months, due to either low ratings or too many ruffled feathers; his relationship with Boris Yeltsin went sour; and readers were no longer interested in his fiction, which had lost its sensational edge. Solzhenitsyn’s 80th birthday in 1998 was more a private than a public affair; his angry rejection of the Order of Andrei Pervozvannyi— the highest honor of the Russian Federation— bestowed on him by Yeltsin was a barely noticed gesture of protest against a morally bankrupt kleptocracy that no longer needed a self-appointed sage speaking truth to power.

Then came Putin, and everything changed. Russia’s new president immediately made advances toward the marginalized author, honoring him as a “living classic,” visiting him at home as early as 2000, and even seeking his political advice. Solzhenitsyn was awarded a State Prize of Russia in 2007 and accepted; the president of Russia once again visited him at his estate and had one last, very long, off-the-record conversation with him. The writer repeatedly spoke out in support of the Russian president, stating that he “brought Russia a slow and steady rebirth.” Simultaneously, Putin’s continued attention fostered the rebirth of Solzhenitsyn’s influence. The apparent alliance between the two was so pronounced that Solzhenitsyn’s sharpest critic, the journalist and Soviet loyalist Vladimir Bushin, pointed to the writer as the conceptualizer leading Putin from behind—one of his books is titled Solzhenitsyn’s Total Project: How Putin Will Reconstruct Russia (2013). French author Mathieu Slama analyzed the similarities between Solzhenitsyn’s worldview and the ideological framework conveyed in Putin’s speeches, identifying state sovereignty, conservatism, and Christian morality as points of consensus.

With Putin’s presidency, the writer’s pamphlets, such as How We Can Reconstruct Russia (1990), which had been ridiculed and then forgotten, suddenly gained in status and were consulted for insights into Putin’s strategy. Indeed, during one of his visits to the writer’s home, Putin pointed out that large parts of his program for Russia’s future were in accordance with Solzhenitsyn’s ideas. More recently, the annexation of Crimea was legitimized with Solzhenitsyn quotes: government loyalists cited the latter’s view that the peninsula should never have been part of Ukraine and should be returned to the Russian Federation.

Endorsement and Subversion

The more Putin’s presidency solidified, the more Solzhenitsyn once again became a public figure of the highest order, only this time endorsed by the Russian establishment and criticized by Western observers. The Solzhenitsyn Prize, awarded by the Solzhenitsyn Foundation, regularly honored geopolitical nationalists such as Aleksandr Panarin. Despite countless attacks launched against him by liberal intellectuals such as Vladimir Voinovich, Solzhenitsyn ultimately succeeded in securing his status as an officially approved classic of Russian culture and thought. Conspicuously, his grave at Donskoi monastery is situated next to those of the émigré philosopher Ivan Ilyin and the historian Vasilii Kliuchevsky.

For Putin, incorporating Solzhenitsyn into the architecture of his Russian reconstruction project had two main functions: firstly, to assure the West that Russia had broken with its communist past for good; and secondly, to assure the Russian citizenry that post-Soviet Russia possessed moral and cultural legitimacy. However, because Solzhenitsyn’s reputation in the West had already declined substantially in the 1980s and 1990s, the first effect was limited. Likewise, the liberal segments of the Russian intelligentsia no longer viewed Solzhenitsyn as the standard-bearer for anti-totalitarianism, but rather as a neo-nationalist to be watched with suspicion. They were particularly disturbed by the fact that Putin’s increasingly illiberal domestic policies did not seem to disturb the writer in the least—a fact that further alienated him from those intellectuals who were critical of the direction that Russia had taken in the new millennium.

Nonetheless, the Putin establishment has remained firm in its endorsement of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn as one of its patron saints. The writer’s funeral in August 2008 was staged as an event of national significance, with both the president and the prime minister in attendance. In 2009, several works by Solzhenitsyn were incorporated into textbooks for Russian high school students, an initiative that was personally proposed by Putin and implemented by then-president Medvedev. Thus, Russia’s youth reads The Gulag Archipelago, albeit in an abridged version composed by the writer’s widow. In 2017, Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (!) proposed marking 2018 as the “Year of Solzhenitsyn.”

Russia’s communists are outraged and frustrated by this massive promotion of Solzhenitsyn, and they are not alone. Critics refer to the disingenuous idealization of the writer’s official image, citing, among other examples, the exclusion of his positive view of the Hitlerite Vlasov Army from the truncated Archipelago tome. Symbolic acts honoring Solzhenitsyn become particular points of contention. Thus, inhabitants of Moscow’s Taganka district passionately protested when Dmitri Medvedev announced the renaming of Grand Communist Street (Bol'shaia Kommunisticheskaia ulitsa, the name it had borne since 1924) into Solzhenitsyn Street just a few months after the writer’s passing. To communists and their sympathizers, such renaming was a provocation. Advocates against Solzhenitsyn correctly described the move as a violation of Russian law, which only allows the naming of a street after an individual a minimum of ten years after the honoree’s passing (the law has since been changed). Although the anti-Solzhenitsyn crowd lost their lawsuit against the city, acts of vandalism, including torn-down street signs, continue to make news. Given the current aggravated mood in Russian society, it is easy to envision that the soon-to-be dedicated Solzhenitsyn monument on Solzhenitsyn Street will likewise become an object of political discontent.

Old Clichés and New Controversies

The statist-militarist segment of Russian society, whose views are most vocally expressed by the weekly Zavtra, maintains a generally hostile view of Solzhenitsyn’s legacy. The two notable exceptions are the editor-in-chief, Aleksandr Prokhanov, and the literary critic Vladimir Bondarenko, both of whom deviate from the paper’s conspiratorial mainstream. Prokhanov, who never ceases to surprise, admits that Solzhenitsyn “heroically fought communism” and that the “red empire was not defeated by the West in battles fought with tanks or rockets but in a competition of meanings (v sostiazanii smyslov).” In that competition, Prokhanov wrote, The Gulag Archipelago was victorious, not The Young Guard and How the Steel Was Tempered.” However, Prokhanov’s generosity with respect to Solzhenitsyn is an anomaly among Russian militarists. More typical among his newspaper’s clientele is the notion of “the agent from Vermont” whose end goal was the destruction of Russia. A major source of Solzhenitsyn’s historical concepts was, according to Zavtra, the YMCA and its publishing arm YMCA Press (including its Russian-language branch, Vestnik RSKhD, and the journal of the same title). Zavtra’s Andrei Fefelov wrote, apparently alluding to his own extravagant editor-in-chief, that “those who believe that during the Cold War (…) there was some loner, a romantic hero who fought the system (…) either don’t understand anything, or they are complete… romantics.” This internal dissent in an otherwise ideologically homogenous newspaper highlights the unease that Solzhenitsyn’s legacy inspires in all levels of Russian society.

Conspicuously, the one aspect of Solzhenitsyn’s legacy never mentioned in the current controversies is his last major work, the monograph 200 Years Together (Dvesti let vmeste). The writer’s attempt to bring clarity to the history of Russian-Jewish relations initially raised eyebrows, even more so than had his political pamphlets of the 1990s. The émigré historian Semen Reznik devoted an entire volume to a thorough analysis of the book and drew a profoundly negative conclusion, charging that not only did Solzhenitsyn fail to discover anything new, but his two-volume opus, with its “lackluster style [and] incohesive composition,” was based on secondary sources that were tendentially and superficially interpreted. Had this unoriginal work appeared under another author’s name, Reznik opined, few people would have paid any attention at all. The fact that the book, with its many formulations that smacked of anti- Semitic clichés, had been written by Solzhenitsyn, however, seriously tainted the writer’s name. As this aspect of his legacy is certainly of no use to the current Russian establishment, the entire causa has simply been ignored during the current commemorations.

Consequences, Intended and Unintended

Solzhenitsyn’s emphatic endorsement of, and by, Vladimir Putin will tie the writer’s reputation to the Russian state for a long time. Due to the profound politicization of his legacy and the impossibility of making a reasonable distinction between the genuinely artistic qualities of his oeuvre (which are the focus of another ongoing controversy) and the effects of his political activism, an objective assessment of Solzhenitsyn—the man and the writer—will remain hard to come by. A related problem is the textological analysis of his legacy: Solzhenitsyn maintained strict control over this process, claiming that the changes he made to his works, for example the novel The First Circle, were de facto reconstructions of the original texts, which had been adjusted to render them publishable and evade censorship. Only a critical historical edition produced by truly independent specialists, without the interference of family members or state authorities, can bring us closer to a future objective assessment of Solzhenitsyn’s oeuvre. Indeed, only a thorough textological analysis will provide answers about the extent to which Solzhenitsyn’s views underwent transformations from the 1950s to the 2000s. (The writer himself carefully avoided that question, claiming that his worldview had fully emerged from the time of his imprisonment.) Without this, the textual basis for any discussion of Solzhenitsyn will remain blurred, enabling representatives of opposing worldviews to take from his fiction and non-fiction whatever suits them.

As for the current Russian administration, it has been instrumentalizing the name and the legacy of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn for a variety of purposes and will continue to do so. Among these purposes are to claim that Russia has irreversibly abandoned the totalitarian communist system; that the Russian state is developing and defending a unique civilization different from all others, especially from Western liberalism; and that the values of this new Russia have been endorsed by the universally recognized heir to Russia’s cultural greatness. These purposes will continue to be activated, regardless of the status of literature proper in Russia’s contemporary culture and education system. Indeed, Solzhenitsyn has become more valuable as a symbolic figure than as an author to be read, with the consequence that the proximity of the writer’s persona and legacy to the Putin establishment will continue to make him a prime object of both official adoration and intellectual disdain.

About the Author

Peter Rollberg is the director the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. He is Professor of Slavic Languages, Film Studies, and International Affairs.

Narva as a Cultural Borderland: Estonian, European, Russophone

By Andrey Makarychev, University of Tartu

Abstract

Looking at Narva, the Estonian city with strong Russian roots, through the lens of culture allows us to see it less as a threat and more as an opportunity. Current Estonian policy seeks to Europeanize Narva, making it cool rather than alien. This effort, instead of pushing Russia aside, provides a platform for Russian artists to perform on an European stage and reach an international audience.

From Geopolitics to Culture

From 1991 when Estonia regained independence, the predominantly Russian-speaking Narva earned a reputation as a borderland city detached from the Estonian political and cultural mainstream. Economic deprivation added a lot to this problematic image. Narva connoted peripherality (both within Estonia and the EU) and was largely perceived in the dominant discourses as Estonian’s “internal other”, often Orientalized due to its cultural connections with Russia. In Russia itself, Narva is referred to as a city with a strong Russian cultural legacy, which, in particular, was verbalized by the presidential candidate Ksenya Sobchak’s controversial statement on the “Russian World” allegedly “stretching from Vladivostok to Narva”.

Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Narva became a security flashpoint with strong military and strategic connotations (Dokladnaya…2016). Based on analogies with eastern Ukraine in spring 2014, multiple alarmist scenarios envisioned that the Kremlin might incite disobedience among Russian speakers, provoke disorder, and infiltrate its “little green men” (Mackinnon 2015). “The main reason for Crimea’s reincorporation into Russia was the inaction of the Ukrainian authorities when it comes to regional development. From this perspective, Ida-Virumaa1 is similar to Crimea… Some say that it is sufficient to make local people cross the bridge and have a look at dilapidated Ivangorod to persuade them not to think about Russia… But we need to create internal magnets within Estonia, rather than persuade people by the claim that our neighbors live worse.” (Denisov 2016).

In the following analysis, I discuss Narva beyond the dominant frameworks of securitization and marginalization (Tiido 2018) and look at this city as a “meeting/ connecting point”, “bridge”, and “hybrid space”. More specifically, I wish to see how performative arts and cultural practices contribute to this transformation of the dominant attitudes to Narva in Estonia. Therefore, I propose to refocus from geopolitics and security studies to cultural semiotics (a discipline that studies signs, cultural representations, and symbols) and cultural governance as a set of tools for fostering social integration and inclusion. The sub-discipline of popular geopolitics— which studies home-grown, vernacular, grass-roots cultural forms and discursive genres—might also be helpful in this regard.

Narva: From ‘A City in Estonia’ to ‘Estonian City’

The official Estonian discourse avoids exceptionalizing Narva and drawing parallels with Donbas or Crimea. Many Russian speakers agree with that approach (Smirnov 2015). “People who live in Narva and who didn’t see the state of the Russian provinces, might believe in a glamour image of Russia created by TV… But I don’t think that Moscow would succeed in utilizing the Russophone diaspora in Estonia the way it did in Donbas”, the former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves assumed (Donbasskiy… 2017). As the current President Kersti Kaljulaid noted, “I have not noticed any troubles with the ‘Russian question’ in Estonian society… In Narva I’ve met with many people striving to act. And language is of secondary importance for that, particularly when I see how well Russian school graduates speak Estonian” (Prezident…, 2017). In the words of the Estonian Interior Minister, “the sunrise from Narva moves to Rakvere and Tartu, Tallinn and Kuresaare, Pärnu and Valga. Estonia starts with Narva” (Stepanov 2018). The view of Narva as a city with a strong Estonian legacy, where many fighters for independence and Second World War prisoners were buried, is lucidly expressed in the EstDoc film festival prize-winning short documentary “Narva 2018: The National Debt” (dir. Maarja Lohmus and Marina Koreshkova).

There were many attempts to rebrand Narva by developing transportation projects, spa and sport facilities, or environmental tourism (Denisov 2015). Symbolically important was that the Estonian President moved her office to Narva for one month in Fall 2018. As a part of the centenary celebration of Estonian independence, she awarded state medals in Narva. It is these attitudes to Narva as a normal Estonian city that stand behind and explain the new cultural policy of the central government that became particularly prominent after the eruption of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. As I will argue further, this policy of Estonization and Europeanization of Narva is not detrimental to Russian cultural identity; on the contrary, it contains new chances for Russian culture to reinstall itself in Estonia and Europe.

Culture Matters

Until recently, cultural life in Narva remained relatively scarce. In the exposition exploring the 1990s which opened in Fall 2018 in the Estonian National Museum in Tartu, Narva is represented as a city where youngsters were mainly interested in alcohol and boxing, with minimal contacts with the rest of Estonia. As other towns of the Ida-Virumaa county, Narva had to deal with the legacy of Soviet industrialization, and struggle with the prospect of peripheralization and transformation into a ‘hollow” and “empty” land devoid of importance for the country. Yet it was a series of politically meaningful cultural projects initiated from Tallinn that raised Narva’s visibility and credentials, and attracted lots of attention to the city.

One of the first steps in the direction of more closely integrating Narva into the Estonian polity was a 2016 photo and video exhibition “How Narva remained with Estonia” dedicated to the 1993 referendum on autonomy in this city. Initially the exhibit was shown in Tallinn’s Museum of Occupation, and then moved to Narva’s city museum. The context of the exposition was implicitly related to the occupation of Crimea and the ensuing debate about the Russian World doctrine. In the words of Katri Raik, the rector of the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences, Narva’s push for greater autonomy was comparable with similar trends towards disintegration in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine (Kak Narva… 2016). Yet today’s lesson of the 1993 referendum—which was ultimately annulled by the Estonian government— is that “here in Estonia we solved all the issues without bloodshed, and nowadays we should be grateful for that to both Russians and Estonians” (Raik 2017).

In 2016 Narva co-hosted an annual Opinions Festival (Festival… 2016), an open forum to publicly address issues of national importance to Estonia. The openness of the discussions inspired some commentators to articulate visible distinctions between Estonia and Russia: “All these free debates take place only 100 meters away from Russia. Yet here the mentality is different: participants listened to drastically dissimilar voices and nobody was afraid of any accusations” (Shtepa 2015).

Since 2016 an important locus for new cultural practices was formed around Narva’s Art Residency,2 a program that started inviting young international artists to spend some time in the city that had a reputation as a small borderland place “in the middle of nowhere”, where there was strong nostalgia for the Soviet past, but an equally strong demand for translating historical memories into the present. In August 2018 the Residency hosted panels of the “Narva – Detroit Urban Lab”, a discussion club seeking to use Western experiences of transforming formerly industrial cities into post-industrial spaces of new lifestyles and cultural practices.

Another salient cultural point in Narva is the territory of Krenholm Manufacture, one of the largest textile producers in Europe in the past. As an industrial enterprise, Krenholm nowadays is technically dead, but its territory can be rejuvenated through new art projects. Recently Krenholm inspired a number of artists who re-imagined it as a space in-between the past and the future, as well as Russia and Europe. The bilingual musical “Kremlin’s Nightingales”—staged by the Tartu-based Uus Teater—in summer 2018 became a highly successful spectacle about the Estonian pop star Jaak Joala, who was a top singer in the late USSR. The show engaged with the Soviet cultural legacy rather than rejecting it, and offered a depoliticized narrative of memory politics that is of particular traction for Narva with its cultural roots in the Soviet past.

In October 2018 Krenholm hosted another theatrical piece named ‘Omen’ and staged “Poetics of a Workers’ Punch”, a production by avant-garde socialist author Aleksei Gastev on the basis of a 1923 poem. This interactive (and bilingual, Russian and Estonian) spectacle deconstructed the glorious image of the industrial age and represented the Krenholm textile plant as an oppressive machine exploiting human beings, and comparable to the repressive apparatus of the Stalinist state.

When it comes to popular culture, a landmark event in 2018 was the Baltic Sun festival that, according to its organizers, in the future might transform into a Europe wide cultural event modeled after the Montreux jazz festival (Vikulov 2018). However, this orientation to Europe created chances for Russian musicians—such as, for instance, the “The Crossroads” and “Bravo” bands— to promote themselves among their European peers.

A similar event that Narva hosted in September 2018 was Station Narva, a festival of contemporary rock and pop music, which also included a number of Russian language public discussions. Again, the festival gave the floor to several performers from Russia (for example, the singer Grechka and the “PSAQ”, “Shortparis” and “Elektroforez” bands) to share the stage with European stars and sing for an international audience. Due to these endeavors “Narva has become hip in Estonia… The abandoned factory buildings, cheap living space and the frisson of sitting on a cultural front line between Russia and the West will attract trendsetters…. Making Narva cool is part of Estonia’s new strategy to integrate Russian-speakers” (Estonia gets… 2018).

The idea of cultural hybridity inspired the local rap singer Yevgeniy Liapin, whose bilingual composition “I am Russian but Love Estonia” (Stuf 2017) became a hit in 2017. Lyapin, a Narva resident and holder of a Russian passport, himself personifies the possibilities of the Russian youth culture to become part of the Estonian cultural milieu and be accepted in this capacity.

By the same token, Narva became a place for a series of cultural projects striving to discuss issues pertinent to the Russophone community. In particular, the exposition “Reflection: a Glance from Inside” (Reflektsioonid … 2016)—first took place in Tallinn and then in Narva— offered an artistic problematization of the hardship of Russian-Estonian linguistic communication. The Estonian artist Evi Pärn in her ‘Manifesto’ issued on the occasion of the exhibit, argued: “I want the media to stop portraying us, speaking different languages, as enemies to each other… Language learning should have nothing to do with coercion and violation of civic rights” (Pärn 2016). In 2018 Pärn was a co-organizer of an ecological art festival titled “Grow and Rot” in Narva’s suburbs, where a major headliner was Max Stropov from the art group “Rodina” known for its performative protest actions in Russia.

The cultural promotion of Narva reached its peak in the application for the title of European Capital of Culture in 2024. It is Tallinn that stands behind Narva’s bid, promoting this cultural project with the strategic political aim of overcoming a deep-seated inferiority complex embedded in Narva’s collective mentality and representing the aspirations of a culturally unified Estonia. The competition for the European Capital of Culture is a core element in the larger project of Europeanizing Narva, yet in the meantime it can also become a springboard for Russian cultural producers to get a stronger foothold in Europe (Kallas 2017).

Some Conclusions

Narva, the most Russian of all cities in the EU, is developing as a cultural space replete with hybrid cultural practices, which creates fertile ground for projecting Russian culture beyond Russia’s national borders. The geographically peripheral Narva is becoming central to Estonia in the sense that the new cultural and political dynamic will define what Estonia is likely to be in the future. Perhaps in the near future Narva can become a laboratory where some post-modern and post-national approaches to language, citizenship and territoriality might be tested. Russian culture might become an integral part of Narva’s rebranding as an Estonian and European city, with a hybrid identity that in the long run might build an alternative to the Kremlin-patronized “Russian World”.

Notes

1 The Estonian region where Narva is located.

2 <external pagehttps://www.nart.eecall_made>

References

- Denisov, Rodion. Privivka ot separatizma na severo-vostoke, Postimees, April 10, 2015, available at <external pagehttps://rus.postimees.ee/3152219/rodion-denisov-privivka-ot-separatizma-na-severo-vostokecall_made>

- Denisov, Rodion. Ruiny Ida-Virumaa ne ukrashayut, May 27, 2016, available at <external pagehttps://rus.err.ee/229754/rodion-denisov-ruiny-ida-virumaa-ne-ukrashajutcall_made>

- Dokladnaya pravite'stvu: Estonia teryaet Ida-Virumaa, Delfi, September 14, 2016, available at <external pagehttp://rus.delfi.ee/daily/estonia/dokladnaya-pravitelstvu-estoniya-teryaet-ida-virumaaid=75617019http://rus.delfi.ee/daily/estonia/dokladnaya-pravitelstvu-estoniya-teryaet-ida-virumaa?id=75617019call_made>

- Donbasskiy stsenariy v stranakh Baltii ne proidiot – eks-prezident Estonii, Krym. Realii, July 10, 2017, available at <external pagehttps://ru.krymr.com/a/28606488.htmlcall_made>

- Estonia gets creative about integrating local Russian-speakers, The Economist, May 10, 2018, available at <external pagehttps://www.economist.com/europe/2018/05/10/estonia-gets-creative-about-integrating-local-russian-speakerscall_made>

- Festival mneniy v Narve: likha beda nachalo. Tvoi Vecher, May 23, 2016. Youtube, available at <external pagehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MH4PZGTELQU&t=354scall_made>

- Kak Narva ne stala estonskim Pridnestroviem. Otkrytaya Rossiya, YouTube, May 13, 2016, available at <external pagehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekGNM9TxKOo&t=2scall_made>

- Kallas, Kristina. Kakoi zhe eschio gorod, kak ne nasha Narva, mozhet stat' v 2024 godu kul'turnoi stolitsei Evropy? Tema, December 15, 2017, available at <external pagehttp://tema.ee/2017/12/15/kristina-kallas-kakoy-zhe-eshhyo-gorod-esli-ne-nasha-narva-mozhet-stat-v-2024-godu-kulturnoy-stolitsey-evropyi/call_made>

- Maciknnon, Mark. In Estonia, a glimpse into the reach of the Russian World, The Globe and Mail, March 6, 2015, available at <external pagehttps://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/in-estonia-the-reach-of-the-russian-world/article23350317/call_made>

- Pärn, Evi. Ruumimängud – lojaalsus ja ühiskond, 2016, available at <external pagehttp://2016.saal.ee/event/502/call_made>

- Prezident Kersti Kaljulaid: Ya veriu v nashikh russkikh, Arvamus Festival, August 12, 2017, available at <external pagehttps://www.arvamusfestival.ee/ru/prezident-kersti-kaljulajd-ja-veru-v-nashih-russkih/call_made>

- Raik, Katri. Narva – estonskiy gorod. Ya rada, chto znayu russkiy. Original TV, YouTube, January 18, 2017, available at <external pagehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sfM27esZrSkcall_made>

- Reflektsioonid: sissevaade / väljavaade. Vol II, available at <external pagehttps://www.narva.ut.ee/et/kolledzist/reflektsioonid-sissevaade-valjavaade-vol-iicall_made>

- Shtepa, Vadim. Narva daliokaya Iiblizkaya. Rufabula, June 9, 2015, available at <external pagehttps://rufabula.com/articles/2015/06/09/narva-distant-and-nearcall_made>

- Smirnov, Ilya. Molodye narvitiane: Kukhonnye razgovory, Postimess, November 6, 2015, available at <external pagehttps://rus.postimees.ee/3389359/molodye-narvityane-kuhonnye-razgovory-eto-odno-a-realno-tut-ne-budet-kak-u-russkihs-ukraincamicall_made>

- Stepanov, Sergey. Stala li Narva Estonskim gorodom? ETV Pluus, February 25, 2018, available at <external pagehttps://etvpluss.err.ee/v/aktuaalnekaamera/videod/4779857b-6b7d-4747-96ff-0509d020f262/stala-li-narva-estonskim-gorodom-ak-ishchet-otvetcall_made>

- Stuf. Olen venelane, YouTube, January 12, 2017, available at <external pagehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLuwoJ2J02Icall_made>

- Tiido, Anna. Where Does Russia End and the West Start? Russia and Estonia, May 14, 2018, available at <external pagehttps://clashintheminds.wordpress.com/2018/05/14/where-does-russia-end-and-the-west-start-russia-and-estonia/call_made>

- Vikulov, Roman. Letom v Narve proidiot muzykal'niy festival, Delfi, April 7, 2018, available at <external pagehttp://rus.delfi.ee/daily/virumaa/letom-v-narve-vpervye-projdet- muzykalnyj-festival-baltic-sun-kotoryj-hotyat-sdelat-odnim-izsamyh-izvestnyh-v-evrope?id=81696275call_made>

About the Author

Andrey Makarychev is a Visiting Professor at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies at the University of Tartu.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.