Tracking Conflict-Related Deaths: A Preliminary Overview of Monitoring Systems

24 Apr 2017

By Irene Pavesi for Small Arms Survey

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageSmall Arms Surveycall_made in March 2017.

Overview

In the framework of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, states have pledged to track the number of people who are killed in armed conflict and to disaggregate the data by sex, age, and cause—as per Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator 16.1.2. However, there is no international consensus on definitions, methods, or standards to be used in generating the data. Moreover, monitoring systems run by international organizations and civil society differ in terms of their thematic coverage, geographical focus, and level of disaggregation. By highlighting these variations and related limitations, this Briefing Paper aims to contribute to the development of a standardized methodology for this indicator.

Key findings

- Data on conflict-related deaths is collected and disseminated mostly by UN missions, academic projects, research institutes, and civil society organizations. Only one country’s national statistical office (NSO)—Colombia’s—currently acts as a source of data on conflict-related deaths.

- Only one-third of the reviewed monitoring systems offer disaggregated data on the sex and age of victims and on the type of weapon used, and even fewer sources gather detailed data on victims’ profiles.

- In the framework of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, partnerships between NSOs and other monitoring systems, including international and non-governmental organizations, can allow for the incorporation of valuable additional data on conflict-related deaths.

- To ensure accuracy and comparability of data on conflict-related deaths—especially if integrative monitoring approaches are to be implemented—common definitions and guidelines must be established to promote the standardization of the collection, verification, and disaggregation of data.

Introduction

Various international organizations and civil society groups are involved in collecting and disseminating information about conflict deaths. While their approaches differ broadly, they may be able to supplement the work of international and national agencies in advancing towards SDG 16, which commits UN member states to ‘[p]romote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’ (UNGA, 2015, p. 14).

In addition, these organizations could inform ongoing efforts to develop a methodology to track conflict-related deaths as part of efforts to ‘[s]ignificantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere’, as specified in SDG Target 16.1. At the time of writing, however, there was no international agreement on a methodology for SDG Indicator 16.1.2— which currently covers ‘conflict-related deaths per 100,000 population, by sex, age and cause’—nor was relevant data generally available at the national level (IAEG-SDGs, 2016).1

This Briefing Paper provides a preliminary overview of the types of organizations that are currently involved in the collection and dissemination of data on conflict-related deaths. After describing the impetus for, and methodology used in, this study, the paper categorizes the reviewed monitoring systems according to their thematic and geographical coverage. It then considers variations in the systems’ applied definitions, methods, and levels of disaggregation, before drawing some conclusions based on the findings. Table 1 lists all reviewed data sources along with their geographical focus and Internet links.

Methodology

The point of departure for this overview was the Survey’s data set on direct conflict deaths, which relies on a pool of sources for relevant information (see Box 1). The initial aim was twofold: 1) to conduct desk-based research during which the net would be cast wider, so as to identify and assess additional, pertinent sources on direct conflict deaths; and 2) to examine the main characteristics of all sources on conflict-related deaths with an eye to constructing a typology.

Box 1 Small Arms Survey data on violent deaths

Since 2004, the Small Arms Survey has tracked violent deaths globally, collecting data from conflict as well as non-conflict settings and focusing on homicides and direct conflict deaths. The Survey has presented its analysis of the data on violent deaths in the Global Burden of Armed Violence reports and in a series of SDG Research Notes (Geneva Declaration Secretariat, 2008; 2011; 2015; Widmer and Pavesi, 2016a; 2016b; 2016c).

The Survey’s direct conflict deaths data covers documented conflict fatalities by any source, including academic centres, civil society organizations, states or state-funded agencies, and international organizations. As of January 2017, the direct conflict deaths data set contained information on fatalities in 36 countries, all of which experienced armed conflict at some point between 2004 and 2015.

In this context, a useful resource was the Casualty Recorders Network, a platform for casualty recording practitioners founded in 2009 by Every Casualty (ECW, n.d.). The Survey’s conflict deaths data set contains information provided by a number of the network’s members.

This review encompasses only publicly accessible primary and secondary sources. It excludes sources that have provided relevant information on an irregular basis, such as general news outlets or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that occasionally publish estimates on conflict-related deaths; instead, it focuses on sources that collect or report conflict death data continuously. This review does not address the question of the reliability of these sources, nor the quality of the data they provide.

This paper uses the term ‘conflict-related deaths’ to refer to people who have died violently during armed conflict; people who lose their lives indirectly during armed conflict—such as due to disrupted access to basic healthcare, food, and shelter— are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Data coverage

Overall, this review has identified 43 unique entities that systematically collect or disseminate data on conflict deaths in 54 different data sets (see Table 1). These sources comprise academic projects, research institutes, civil society organizations, national statistical offices (NSOs), and international organizations. Each monitoring mechanism places an emphasis on a particular aspect of conflict deaths and collects data for a given geographical area—whether global or more local—as discussed below.

Thematic coverage

Most systems are designed to document the number of civilians and the number of combatants reported to have died in a given conflict. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), for instance, is mandated to monitor the situation of civilians in order to coordinate protection and promote accountability (UNAMA, 2016). Similarly, Iraq Body Count has recorded details on violent deaths of civilians since the 2003 military intervention in Iraq (IBC, n.d.). Both civilian and combatant deaths are monitored by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, which has been in operation since June 2011 (SNHR, n.d.b). Other sources focus on the motivations for violence; they may monitor deaths that occur as a result of political violence or terrorism, for example. Still other sources focus on people who lose their lives as a result of human rights violations, or they may count victims to assess the impact of specific weapons, such as drones or explosives (referred to as ‘explosive violence’).

Geographical focus

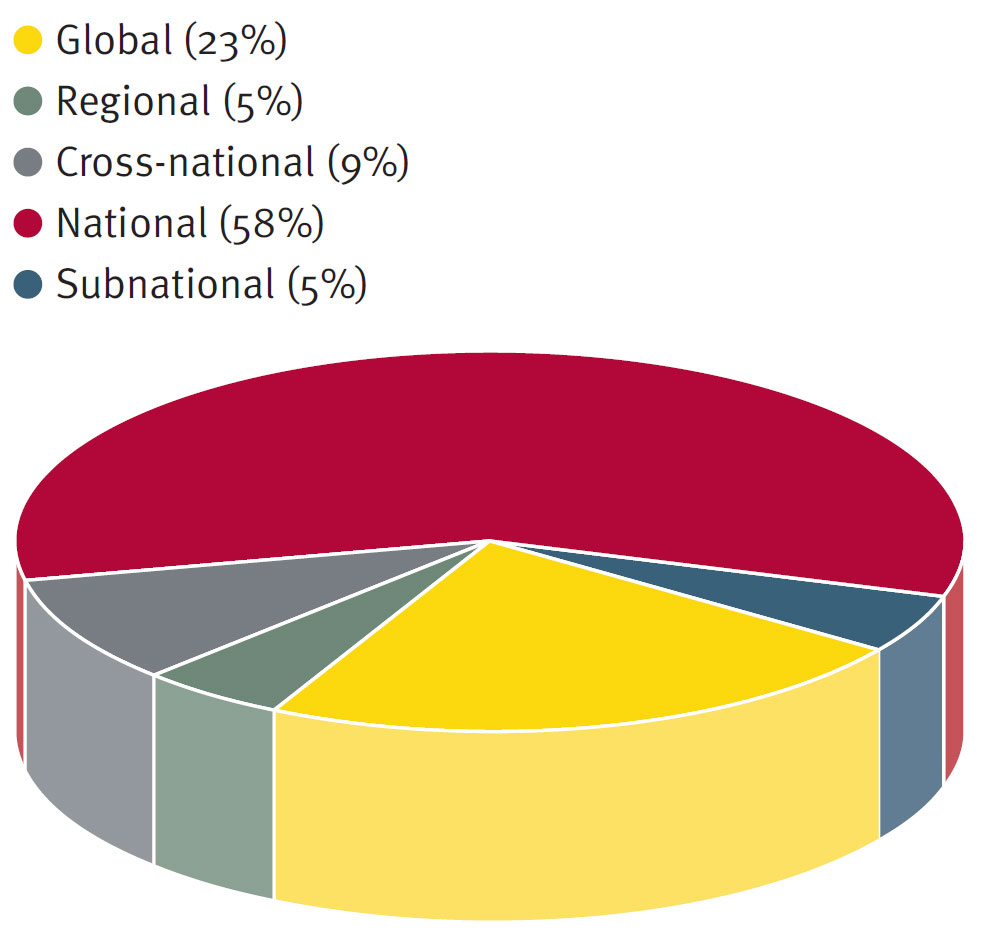

The monitoring systems can also be grouped by their geographical coverage (see Figure 1). Within these geographical categories, they may cover a specific conflict, killing mechanism, or armed group.

Figure 1 Sources by geographical coverage of conflict-related deaths (N=43)

Ten of the 43 sources have global coverage; they report the number of fatalities from documented armed conflicts. This group includes the three data sets provided by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), the Global Terrorism Database of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland, and the Armed Conflict Database compiled by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (UCDP, 2015; 2016a; 2016b; START, n.d.; IISS, n.d).

Two sources have regional coverage, including the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), which focuses on conflicts in Africa and Asia (ACLED, n.d.).

Four sources have cross-national coverage and track the number of victims caused by specific mechanisms or actors. Three of these sources document the human toll of explosive violence in different conflicts. Airwars, for example, provides data on the victims of international airstrikes in Iraq, Libya, and Syria (Airwars, n.d.); meanwhile, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism records the victims of US drone strikes in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen (BIJ, n.d.). One source, the LRA Crisis Tracker, records fatalities attributable to a single armed group: it monitors violence carried out by the Lord’s Resistance Army in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), South Sudan, and Sudan (LRA Crisis Tracker, 2015, p. 8).

Just over half of the sources have a national focus. These can be divided into two categories: national monitoring systems that capture conflict deaths by tracking mortality due to violence, and monitoring systems that were established in response to the outbreak or the intensification of armed conflict.

Five sources fall into the first category, including national institutions and observatories. Among them is the Colombian National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, which compiles data from morgues and public health institutions (INMLCF, 2016, pp. 9–10.). The Institute’s reports on deaths due to ‘external causes’ specify whether deaths are the result of interpersonal violence or sociopolitical violence; for 2015, it recorded 1,630 of the former and 345 of the latter (p. 83). Another Colombian source—the country’s NSO—releases annual statistics on mortality by cause of death, including aggregated figures on deaths resulting from legal interventions and operations of war, as defined by the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (DANE, n.d.; WHO, 2016).

The second category consists of 20 monitoring systems that document the impact of war in specific contexts. Examples include Iraq Body Count, the Syrian Network for Human Rights, and UNAMA (IBC, n.d.; SNHR, n.d.; UNAMA, n.d.).

The two remaining sources have a subnational focus: Deep South Watch monitors political violence in Thailand’s southern border provinces in its Deep South Incident Database, and the Caucasian Knot reports monthly statistics of victims in the northern Caucasus (DSW, n.d.; Caucasian Knot, n.d.).

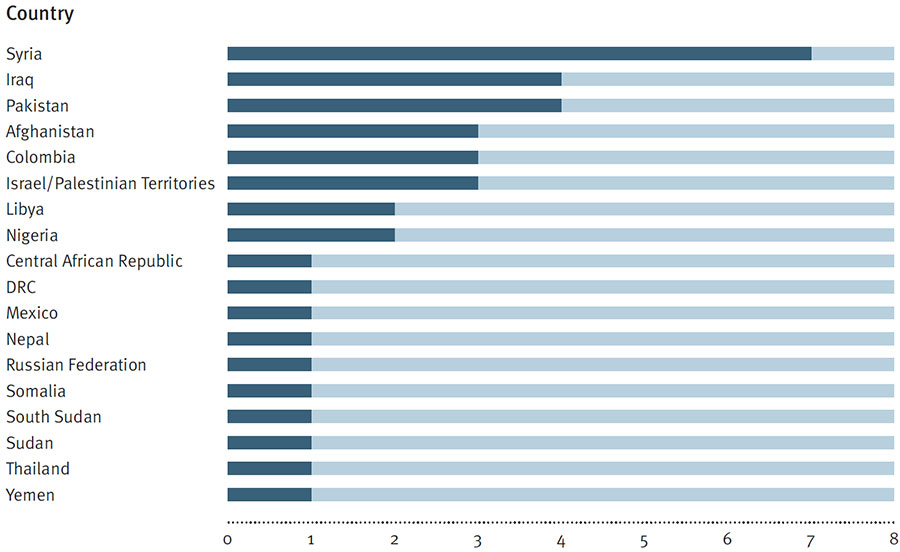

Figure 2 Number of monitoring systems by country (N=31)*

Figure 2 shows the countries for which conflict-related deaths are tracked by the sources under review, excluding those with global and regional coverage. The conflict in Syria is the most documented; seven organizations track fatalities in this conflict. It is followed by the conflicts in Iraq and Pakistan, each of which is covered by four conflict-specific monitoring systems.

Definitions

The reviewed monitoring systems use varying definitions and methodologies to monitor conflict-related casualties. Academic institutions tend to provide more detailed information about their definitions of armed conflict than other sources.

UCDP differentiates between state-based conflict, non-state conflict, and one-sided violence (UCDP, 2015; 2016a; 2016b). The first of these types of conflict is defined as ‘a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory over which the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, has resulted in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year’ (UCDP, 2015, p. 5). Non-state violence is ‘[t]he use of armed force between two organised armed groups, neither of which is the government of a state’ and one-sided violence is ‘[t]he use of armed force by the government of a state or by a formally organised group against civilians’ (UCDP, 2016a, p. 2; 2016b, p. 2). To fall into the latter two categories, the recorded violence must also result in at least 25 conflict-related deaths per year. These definitions are akin to the concept of direct conflict deaths in that the deaths must result directly from acts of armed violence, rather than indirectly in the context of war.

In contrast, ACLED focuses on motivations behind violent acts. It defines political violence as a ‘single altercation where often force is used by one or more groups to a political end’, such as in civil and communal conflicts, violence against civilians, remote violence,2 and rioting and protesting—both in and outside the context of civil war (ACLED, 2015, pp. 4–7). Unlike the UCDP database, which excludes deaths resulting from clashes between unidentifiable armed groups, ACLED collects data on conflicts between organized but unidentified armed groups as well as actors engaged in more spontaneous acts of disorganized violence, such as rioters, protesters, and civilians (pp. 4–7).

The ICD, currently in its tenth revision, provides a standardized taxonomy on causes of death to guide the recording of mortality statistics. ICD-10 classifies deaths that result from external causes, including self-directed violence; interpersonal violence; and collective violence, which is defined as ‘[l]egal intervention and operations of war’ (WHO, 2016, ch. XX). Deaths from operations of war include ‘injuries to military personnel and civilians caused by war and civil insurrection’ as well as deaths caused by ‘war operations occurring after cessation of hostilities’ (ch. XX).

The UN’s International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS) seeks to promote international comparability of statistical data (UNODC, 2015). With respect to intentional and unlawful killings, the ICCS distinguishes between killings during civil unrest and killings during armed conflict, applying the relevant legal frameworks to each situation (UNODC, 2015, pp. 17–18). According to the ICCS, killings that occur during ‘civil unrest’ are to be categorized as intentional homicides, given that criminal law—rather than international humanitarian law—would be applicable in such cases. In situations of armed conflict, the ICCS makes a distinction between killings that can be classified as ‘war crimes’ under international humanitarian law (such as targeted or excessive killings of civilians) and killings that are criminal offences under applicable national legislation (pp. 17–18).

Methods

Short of actually collecting primary data on conflict-related deaths, most of the monitoring systems reviewed in this paper gather such information from a small pool of primary sources. The tracking of conflict-related casualties is typically based on incident reporting from a range of sources, such as reports by the media, the military, government institutions, international organizations, and NGOs. Information can also be collected from witnesses through crowdsourcing. Syria Tracker’s map of violent events, for example, combines data from media sources with information provided anonymously by civilians who use encrypted technology (Humanitarian Tracker, n.d.). The documentation of conflict-related deaths may also be undertaken by teams of casualty recorders on the ground. Such recorders collect information directly from a range of actors, including eyewitnesses, healthcare personnel, and community leaders.

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides global statistics on mortality by cause of death and by sex and age, based on ICD-10 classifications. These statistics draw on vital records, wherever these are available and sufficiently complete, or estimation models if data is unobtainable or incomplete. Estimation models use previously released data from the country, information from neighbouring countries, and additional information on specific types of death. The Global Health Estimates, for instance, provide aggregated estimates on ‘collective violence and legal intervention’, a term previously used for what the most recent ICD-10 classifies as ‘legal intervention and operations of war’ (categories Y35–Y36) (WHO, 2013, p. 46; 2014, p. 11; 2016).

In order to generate its estimates on conflict deaths, WHO adjusts information provided in the three UCDP data sets (see above). Specifically, WHO applies an adjustment factor to the UCDP state-based conflict data set to offset undercounting; it also draws on additional information in order to assess conflict deaths in Iraq and Syria, such as country-level data on landmines (WHO, 2014, pp. 20–21). Since this data is aggregated under the relevant legal category (‘legal intervention’), however, it precludes calculations of conflict-related deaths per conflict or country.

Each reviewed monitoring system entails a validation process that crosschecks information to ensure accuracy and completeness. The systems vary greatly in the amount of information they provide on their sources and the methods they use for coding and validation. Details on approaches were not available or were unclear in almost one-third of the reviewed cases.

Disaggregation

Data on conflict-related deaths may be disaggregated by basic demographic characteristics of victims, such as age and sex, as well as their status, such as whether they were civilians or combatants. Details on the causes of death, including the type of weapon used to kill and the location of conflict-related events, are not provided for all incidents.

Casualty recorders tend to document conflict-related deaths at either the incident or individual level (Minor, 2012, p. 7). Monitoring systems that track deaths at the incident level record the number of killings that occurred during a conflict event; in contrast, systems that compile records of individual victims tend to reflect their socio-demographic details as well as the circumstances of their deaths.

Most of the sources under review provide aggregated figures for fatalities among both civilians and combatants, although not all disaggregate the number of victims by their status. The terms and definitions used for civilians and combatants differ across sources, hampering the comparison of data. Within each of these categories, the counting of violent deaths may be limited further. For example, the Aid Worker Security Database, a project of Humanitarian Outcomes, provides data on security incidents only if they affect aid workers (Humanitarian Outcomes, n.d.).

Information that is disaggregated by subnational entities is provided by slightly more than half of the sources under review, some of which generate georeferenced data and detailed maps of conflict events. One-third of the reviewed monitoring systems offer some information on the type of weapon used, yet fewer sources gather detailed data on victims’ profiles. When it comes to the sex and the age of victims, just one-third of the monitoring systems provide systematically disaggregated data.

Conclusion

This paper has reviewed monitoring mechanisms of conflict-related deaths with a view to informing the development of a methodology for tracking changes in the values of Indicator 16.1.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Various sources currently track conflict-related deaths, yet only one country’s national statistical office—Colombia’s— is involved in data collection efforts. While NSOs are expected to play a central role in monitoring the implementation of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, their capacity and impartiality may be jeopardized or undermined due to operational constraints or political interference in conflict-affected settings. In view of these limitations, the monitoring and dissemination of data on conflict deaths falls to an integrative or hybrid system of entities that measure the human toll of armed conflict, including international organizations and NGOs.

Integrative approaches to monitoring conflict-related deaths require the establishment of guidelines and common definitions and standards to ensure accuracy and comparability of data.3 Ideally, such standards specify the means of data gathering on the ground, verification procedures applicable to various conflict contexts, and levels of disaggregation for conflict-related deaths. At a minimum, data should be disaggregated by age, sex, and status of victims as well as by the weapon involved.

Recognizing the complexity of data gathering in conflict settings and the multitude of actors involved in such endeavours, the Small Arms Survey invites practitioners and other stakeholders to provide input to help make this review—a work in progress—as comprehensive and as useful as possible. Updates of this review will be released in response to feedback.

Notes

1 The work on the development of Indicator 16.1.2 is led by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, with the support of a group of experts in the Praia Group on Governance Statistics (IAEG-SDGs, 2016, p.25; Praia Group, n.d.).

2 ACLED defines incidents of remote violence as ‘events in which the tool for engaging in conflict did not require the physical presence of the perpetrator. [. . .] These include bombings, IED [improvised explosive device] attacks, mortar and missile attacks, etc.’ (ACLED, 2015, p. 13).

3 See, for example, the Standards for Casualty Recording, which were released by Every Casualty Worldwide in November 2016 (ECW, 2016).

References

ACLED (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project). 2015. ‘Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) Codebook.’

—. n.d. ‘About ACLED.’

Airwars. n.d. Website. Accessed August 2016. BIJ (Bureau of Investigative Journalism). n.d. ‘Covert Drone War.’

Caucasian Knot. n.d. ‘North Caucasus: Statistics of Victims.’ Accessed August 2016.

DANE (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística). n.d. Defunciones por causa externa.

DSW (Deep South Watch). n.d. ‘Deep South Incident Database.’

ECW (Every Casualty Worldwide). 2016. Standards for Casualty Recording, Version 1.0. 23 November.

—. n.d. ‘Casualty Recorders Network.’

Geneva Declaration Secretariat. 2008. Global Burden of Armed Violence. Geneva: Geneva Declaration Secretariat.

—. 2011. Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011: Lethal Encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—. 2015. Global Burden of Armed Violence 2015: Every Body Counts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Humanitarian Outcomes. n.d. ‘The Aid Worker Security Database.’ Accessed August 2016.

Humanitarian Tracker. n.d. ‘Syria Tracker.’

IAEG-SDGs (Inter-agency Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goals). 2016. ‘Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators.’ December.

IBC (Iraq Body Count). n.d. ‘Documented Civilian Deaths from Violence.’ Accessed August 2016.

IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies). n.d. Armed Conflict Database. Accessed August 2016.

INMLCF (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses). 2016. Forensis 2015: Datos para la vida. Bogotà: INMLCF.

LRA Crisis Tracker. 2015. ‘Map Methodology & Database Codebook v2.’

Minor, Elizabeth. 2012. An Overview of the Field. London: Oxford Research Group.

Praia Group (on Governance Statistics). n.d. ‘Working Groups on Sustainable Development Goal 16 Indicators.’ Draft.

Small Arms Survey. 2016. ‘Matrix on Conflict-related Deaths.’ Unpublished background document.

SNHR (Syrian Network for Human Rights). n.d.a. ‘Syrian Network for Human Rights: Truth and Justice Comes First.’

—. n.d.b. Website.

START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism). n.d. Global Terrorism Database. United States Department of Homeland Security, University of Maryland. Accessed August 2016.

UCDP (Uppsala Conflict Data Program). 2015. ‘UCDP Battle-Related Deaths Dataset Codebook.’ Uppsala University.

—. 2016a. ‘UCDP Non-State Conflict Codebook.’ Uppsala University.

—. 2016b. ‘UCDP One-sided Violence Codebook.’ Uppsala University.

UNAMA (United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan). 2016. ‘Afghanistan Midyear Report 2016: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict.’ Kabul: UNAMA.

—. n.d. ‘Reports on the Protection of Civilians.’

UNGA (United Nations General Assembly). 2015. Resolution 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Adopted 25 September. A/RES/70/1 of 21 October 2015.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). 2015. ‘International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS).’ Version 1.0. WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. ‘

WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Causes of Death 2000–2011.’ Geneva: WHO. June.

—. 2014. ‘WHO Methods and Data Sources for Country-level Causes of Death 2000–2012.’ Geneva: WHO.

—. 2016. ‘ICD-10 Version:2016: Legal Intervention and Operations of War (Y35–Y36).’ Accessed September 2016.

Widmer, Mireille and Irene Pavesi. 2016a. ‘Monitoring Trends in Violent Deaths.’ Research Note No. 59. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. September.

—. 2016b. ‘Firearms and Violent Deaths.’ Research Note No. 60. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. October.

—. 2016c. ‘A Gendered Analysis of Violent Deaths.’ Research Note No. 63. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. November.

Table 1 Reviewed sources of data on conflict-related deaths

About the Author

Irene Pavesi is a researcher at the Small Arms Survey and since 2012 she has been managing the organization’s database on violent deaths.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.