Overseas Contingency Operations: The Pentagon´s $80 Billion Loophole

29 May 2017

By Laicie Heeley for Stimson Center

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageStimson Centercall_made on 23 May 2017.

Summary

The Trump administration’s fiscal 2017 supplemental request and Congress’ resulting appropriation have ushered in a new era of budgetary irresponsibility. Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), once a designation meant to increase transparency and shield war spending from the threat of sequestration, has eroded to include billions of dollars in base budget needs. In 2017, the designation has come to serve as little more than an expensive loophole in existing law. This report details the following examples of abuse and distortion of OCO funds:

- Fiscal 2017 omnibus appropriations include $82.4 billion in OCO spending, a 41 percent increase over the previous fiscal year. President Trump’s initial $30 billion supplemental request for fiscal 2017 included $5 billion in OCO-designated funds and $25 billion in additional base spending. Congress ultimately granted only $18 billion, but shifted the whole of the sum into OCO, leading to significant growth in base OCO-designated funds.

- In the past, the Pentagon has acknowledged that approximately half of OCO is now used to supplement its base budget. But the Pentagon’s estimate is just that, since its accounting systems don’t currently require it to differentiate between wartime accounts and routine operations.

- The effect of the shift from base to OCO spending can be partially illustrated by calculating the cost of a single troop, which has grown from approximately $1 million in fiscal 2008 to $5.9 million in fiscal 2017, a 590 percent increase.

- While the issue has received less attention, the foreign affairs base budget has also benefited from this process of abuse. As a result, in recent years, base foreign affairs funding has decreased, while OCO foreign affairs funding has increased significantly.

- The use of OCO relies on Congress and the president to “designate” certain activities as compliant with present regulations. But current OCO guidance, which is based on an association with a specified region, has not been updated to cover the full scope of activities now designated as OCO.As a result, current criteria do not address OCO-funded operations in areas such as Syria and Libya, new initiatives such as the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), or base budget requirements such as readiness.

The following actions are recommended in response to this growing abuse of OCO:

- Congress must end the charade. Eliminate the Budget Control Act caps and use of the OCO designation and fund all of defense spending through the normal budgetary process so that normal controls and decision-making can prevail.

- Short of eliminating OCO, DOD must work with OMB to revise and strengthen the criteria for determining what can and cannot be included in OCO appropriations.1

- DOD must further develop and maintain a reliable estimate of enduring OCO costs supported by updated accounting procedures. This estimate should be reported in future budget requests.2

While transitioning longer-term OCO expenses to the base budget may be difficult under budget caps, it is necessary to return some semblance of order and fiscal responsibility to the budget process.

Introduction

On May 4, 2017, Congress voted to pass a $1.16 trillion government spending bill that funds operations through the end of the fiscal year. In the bill, Defense Department spending received an increase of $25.7 billion over fiscal 2016 and $22.1 billion over President Obama’s original request for a total appropriation of $598.5 billion. Since defense spending remains subject to caps imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), however, much of this increase was funded through the use of a loophole. At $82.4 billion, the bill’s fiscal 2017 funding designated as Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) represents a 41 percent increase over the previous fiscal year. This surge in OCO spending, while partially justified by the expansion of operations in Iraq and Syria, is an abuse of the OCO designation’s intent and a clear effort to circumvent the budget caps.

This brief report will examine increases in OCO abuse in the most recent budget cycle as well as the distortion of OCO’s intent over time. It will further explore a path forward as Congress and the administration grapple with the continued utility of the designation under the BCA caps. As the OCO designation has moved far afield of its original intent, the BCA’s use as a budget control measure has come into serious question. This report will argue that the time has come to rethink its use.

Increasing Abuse

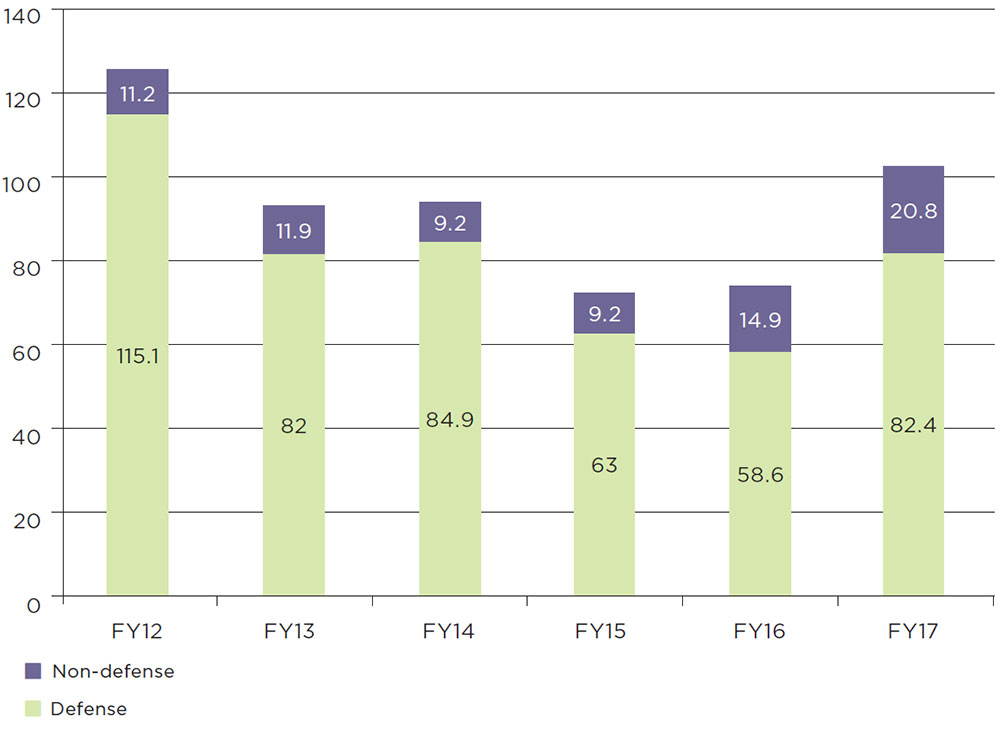

In recognition of ongoing OCO abuse, which has largely been normalized in Congress, the Pentagon acknowledged in September 2016 that approximately $30 billion in OCO per year is used to supplement its base budget.3 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) further reported in August, 2016 that the Pentagon’s accounting systems don’t currently require it to differentiate between wartime accounts and routine operations, adding to an already blurred line between the two.4 And this issue is not limited to defense. Particularly in recent years, as the practice of shifting base funds to OCO has gained traction in Washington, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) has noted that the foreign affairs base budget has decreased while the foreign affairs OCO budget has increased significantly — “thereby meeting the budgetary caps without reducing overall foreign affairs funding.”5 Figure one explores recent trends in defense and non-defense OCO spending, illustrating recent increases in both.

This lack of oversight and transparency, combined with the incentive to evade current legal budgetary limits through the employment of OCO, has led to significant and growing abuse of the designation. As a result, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) recently told reporters that “[OCO] has become nothing but a fancy slush fund.”6

The Trump Administration’s Request

According to the Department of Defense, additional OCO funds requested by the Trump administration in March and enacted in May 2017 would represent “the first step in a multiyear process of rebuilding the U.S. Armed Forces into a larger, more capable, and more lethal joint force that can execute the national defense strategy and protect U.S. interests worldwide.” The funds would be used for three purposes: 1) Accelerating operations in Iraq and Syria; 2) Increasing readiness; and 3) Covering new bills that have arisen over the course of the fiscal year.

Figure 1: Trends in Total OCO-Designated Spending FY2012-FY2017

(in billions of current dollars)

Trump’s initial $30 billion supplemental request included $5 billion in OCO-designated funds and $25 billion in additional base spending to support these priorities. Congress ultimately granted only $18 billion of the Trump administration’s initial $30 billion request, but placed the whole of the sum in OCO, leading to significant growth in OCO-designated funds, and particularly in those traditionally appearing in the base.

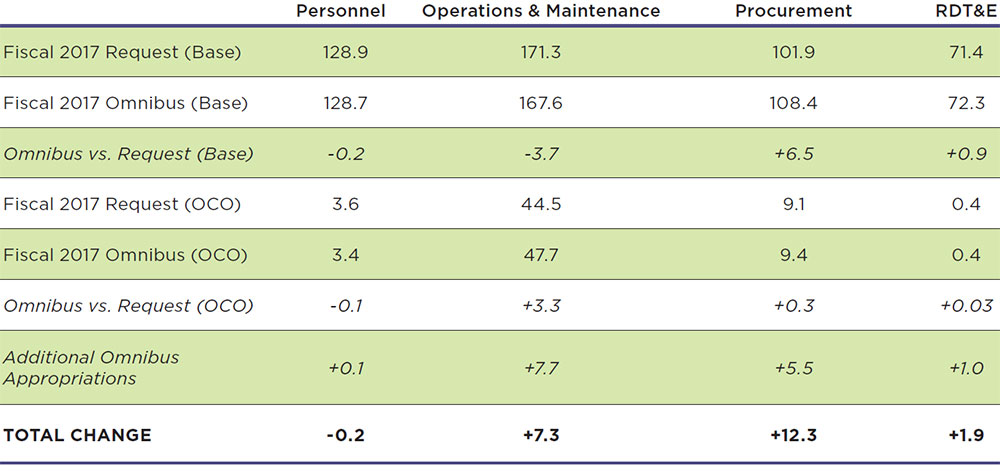

Table one illustrates major changes to base and OCO spending in the fiscal 2017 omnibus spending bill. The legislation provides large overall increases to procurement and operations and maintenance (O&M). The $5.8 billion in supplemental funds provided in December were also slated almost entirely for O&M ($5.1 billion). Rising O&M costs reflect the rising, and seemingly runaway, price of fielding a single troop, as seen in Figure two. But, out-of-control O&M is not the only explanation for the rising cost of fielding a single troop. In addition to funding critical war fighting needs and recapitalization, omnibus OCO funds include $75 million in training and support costs for the F-35, $151 million in procurement costs for the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-ballistic missile defense system, and other base budget priorities.

Tables 1: Fiscal 2017 Omnibus Spending by Major Title

(in billions of current dollars)

Distortion of OCO’s Intent

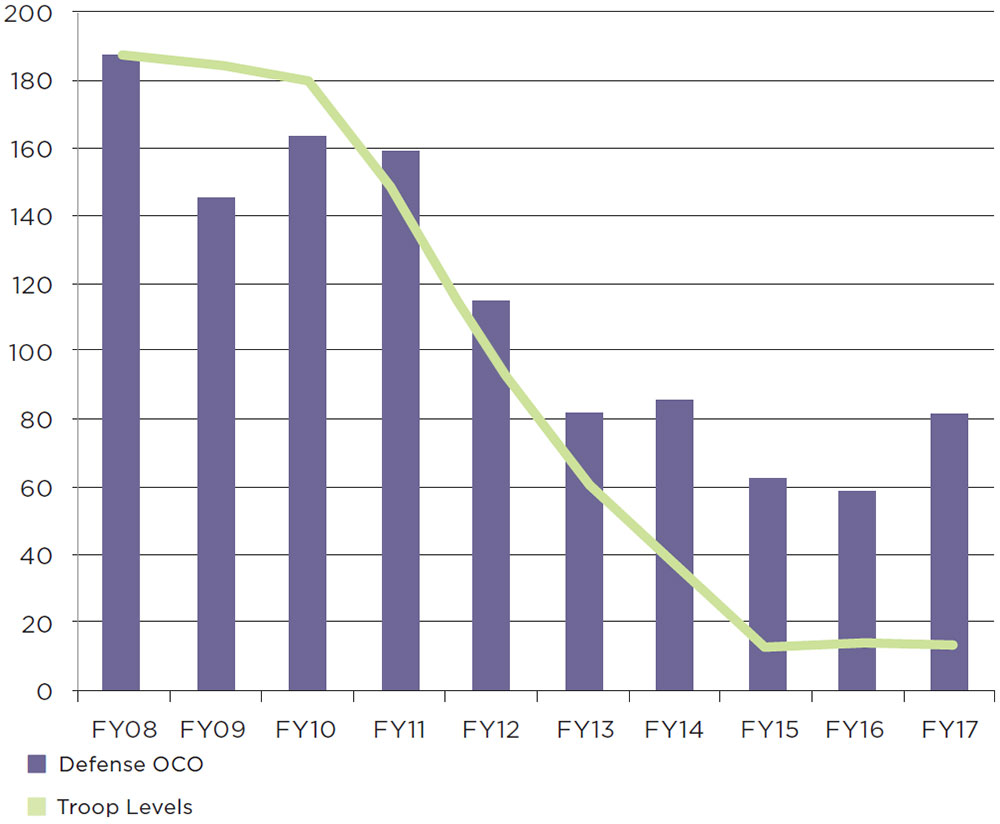

Over time, an overall decrease in U.S. troop levels overseas has been offset by additional base budget funding and resources dedicated to other initiatives such as the European Reassurance Initiative and the Counterterrorism Partnership Fund.

Figure two highlights the widening gulf between troop levels and OCO-designated defense spending. At its peak in fiscal 2008, OCO spending rose to $187 billion. At this time, 154,000 troops remained in Iraq and 33,0000 in Afghanistan, for a total of 187,000 troops deployed in the two theaters. This troop level reflects a cost of $1 million per troop. In fiscal 2017, the Pentagon will receive $82.4 billion for OCO, with just over 14,000 total troops projected overseas. This total includes $58.6 billion requested by President Obama, as well as $5.8 billion in supplemental funding for operations in Syria and Afghanistan enacted in December, and $18 billion in additional funds provided as part of the fiscal 2017 omnibus spending bill. As a result, these increases reflect a cost of approximately $5.9 million per troop, a 590 percent increase since fiscal 2008.

OCO Regulations

Current DOD financial management regulations (FMR) state that OCO-designated funds may be used:

… only for those incremental costs incurred in direct support of a contingency operation. As such, funds that are transferred into a Component’s baseline appropriation are not to be used to finance activities and programs that are not directly related to the incremental cost of the contingency.7

These regulations define contingency operations costs as costs “that would not have been incurred had the contingency operation not been supported.”8 A “contingency operation” is defined in Section 101 of Title 10, United States Code as any Secretary of Defense-designated military operation “in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing military force.” The use of OCO, however, relies on Congress and the president to “designate” certain activities as compliant with these regulations. In recent years, use of the OCO designation has expanded to include not only wartime activities, but base budget needs.9

Figure 2: Trends in Recent Troop Levels and OCO-Designated Spending

(in billions of current dollars/annual average in thousands)

Further, current OCO guidance issued by OMB and most recently updated in 2010 does not cover the full scope of activities now designated as OCO. Current criteria identify items and activities eligible for OCO funding based on an association with a specified region in which operations are occurring. The criteria also exclude certain activities, such as equipment service-life extension programs, family support initiatives, and maintenance of industrial base capacity. Since 2010, however, the scope of activities included in OCO has expanded beyond the current criteria. As a result, current criteria do not address OCO-funded operations in areas such as Syria and Libya, new deterrence and counterterrorism initiatives such as the European Reassurance Initiative, or base budget requirements such as readiness.10 As is evidenced in recent appropriations, this lack of clear guidance has allowed the mission of OCO to begin to look less like funding for contingency operations and more like the mission of the Department itself: “to provide the military forces needed to deter war and to protect the security of our country.”11

Conclusions and Recommendations

Prior to the passage of the BCA, the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA) allowed only “emergency” requirements to be excluded from budget control limits. The BCA, however, added OCO to this exemption, providing Congress and the president with a workaround. The intent of this exemption made sense at the time, since war funds were, as part of their very nature, emergency funds, and should thereby be excluded from funding limits. This exemption no longer makes the same sense. The U.S. has been at war in the Middle East for nearly 17 years. Most activities related to contingency operations can now be anticipated in advance, as evidenced by the OCO budget submission process, which traditionally occurs at the same time as the base budget request. Moreover, emergency supplemental appropriations remain an option for unforeseen needs.

The Pentagon, the president, and bipartisan members of Congress have participated willingly in abuse of the OCO designation in its current form, using the threat of sequestration to drive increases in both defense and domestic spending. But this issue may have reached a breaking point. Since the passage of the BCA in 2011, Democrats have fought consistently for parity between defense and domestic spending, and won. Democrats continue to stand in united opposition to any legislation that raises defense spending at the expense of domestic, and continue to win increases to domestic spending as a result. In recent years, however, large increases in OCO and revelations regarding the Pentagon’s funding of base budget needs have drawn attention to the farce that parity has become. Moving forward, lawmakers will have a hard time arguing for the continued existence of the budget caps, or, for that matter, for parity between defense and domestic spending, if the caps effectively only apply to one side.

What was once meant to drive increased transparency and protect war spending from the threat of sequestration has become a loophole in existing law that allows defense funding to rise without constraint. Thus, the following actions are recommended:

- Congress must end the charade. Eliminate the BCA caps and fund all of defense spending through the normal budgetary process so that normal controls and decision-making can prevail.

- Short of eliminating OCO, DOD must work with OMB to revise and strengthen the criteria for determining what can and cannot be included in OCO appropriations.12

- DOD must further develop and maintain a reliable estimate of enduring OCO costs supported by updated accounting procedures. This estimate should be reported in future budget requests.13

Transitioning longer-term OCO expenses to the base budget may be difficult under budget caps. But the caps themselves have been corrupted beyond anything but political use. Because of its designation as war funding, OCO does not currently receive the same scrutiny as base budget funds, and its continued abuse has allowed overall spending to rise unchecked. Having been distorted and widely abused, it is past time for Congress to reconsider the use of the OCO designation at all.

Notes

1.Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Overseas Contingency Operations: OMB and DOD Should Revise the Criteria for Determining Eligible Costs and Identify the Costs Likely to Endure Long Term.” U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). January, 2017. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/682158.pdf.

2.Ibid.

3. Bertuca, Tony. “Pentagon will need to fund ‘enduring requirements,’ now in OCO account, once combat ends.” Inside Defense. September 30, 2016. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://insidedefense.com/share/181524.

4. Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Overseas Contingency Operations: OMB and DOD Should Revise the Criteria for Determining Eligible Costs and Identify the Costs Likely to Endure Long Term.” U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). January, 2017. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/682158.pdf.

5. Williams, Lynn M., and Susan B. Epstein. “Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status.” Congressional Research Service. February 7, 2017. Accessed May 9, 2017. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R44519.pdf.

6. Snell, Kelsey, and John Wagner. “Republicans argue they won plenty in spending deal, too.” The Washington Post. May 02, 2017. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/republicans-argue-they-won-plenty-in-spending-deal-too/2017/05/02/b33c5680-2f6c- 11e7-9dec-764dc781686f_story.html?utm_term=.ad219c5c99ed.

7. United States. “Volume 12, Chapter 23: “Contingency Operations” Summary of Major Changes.” Department of Defense. September 2007. Accessed May 9, 2017. http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/documents/fmr/current/12/12_23.pdf

8. Ibid.

9. Williams, Lynn M., and Susan B. Epstein. “Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status.” Congressional Research Service. February 7, 2017. Accessed May 9, 2017. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/ natsec/R44519.pdf.

10. Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Overseas Contingency Operations: OMB and DOD Should Revise the Criteria for Determining Eligible Costs and Identify the Costs Likely to Endure Long Term.” U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). January, 2017. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/682158.pdf.

11. “About the Department of Defense (DoD).” U.S. Department of Defense. Accessed May 11, 2017. https://www.defense.gov/About/.

12. Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Overseas Contingency Operations: OMB and DOD Should Revise the Criteria for Determining Eligible Costs and Identify the Costs Likely to Endure Long Term.” U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). January, 2017. Accessed May 09, 2017. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/682158.pdf.

13. Ibid.

About the Author

Laicie Heeley is a Fellow with Stimson’s Budgeting for Foreign Affairs and Defense program.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.