MPCC: Towards an EU Military Command?

13 Jun 2017

By Thierry Tardy for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 7 June 2017.

The November 2016 Council Conclusions on the implementation of the EU Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS) invited the High Representative to present proposals to establish, ‘as a short term objective, and in accordance with the principle of avoiding unnecessary duplication with NATO’, ‘a permanent operational planning and conduct capability at the strategic level for non-executive military missions’. This new structure, to be called ‘military planning and conduct capability’ (MPCC) in analogy to its civilian counterpart (Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability, CPCC) and formally created on 8 June, may well be one of the most tangible deliverables of the latest efforts to revitalise EU defence policy. Although not necessarily revolutionary in nature it is symbolic of a certain evolution of mindset after more than 15 years of politicised discrepancies among member states on the virtues of an EU proper command structure.

Planning EU operations

The development of a Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has since its very inception combined a mix of doctrinal thinking, the establishment of institutions and the creation and conduct of operations. At the institutional level, what emerged in the early 2000s as the politico-military structure was to enable the EU to decide upon, create, plan, command and run a wide range of CSDP activities, with some degree of autonomy vis-à-vis other organisations, namely NATO.

The institutions created were initially largely copied from their NATO equivalents, yet political divergences on what ‘autonomy’ meant, or resistance to the establishment of overly-ambitious structures in the name of non-duplication with NATO, prevented the EU from acquiring a full operational planning and conduct capacity.

As a consequence, in the case of ‘major’ or ‘executive’ military operations (‘executive’ operations are operations mandated to conduct actions in replacement of the host nation), planning (at the military strategic level) has been conducted externally through two mechanisms. The first is the option to resort to NATO planning assets as per the terms of the 2003 EU-NATO Berlin Plus agreement (only operation Althea in Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponds to this format today). The second option is to resort to one of the five national headquarters (in France, Germany, Greece, Italy, and the UK) earmarked for EU autonomous operations. All five national HQs have been used by the EU. A third option, never implemented to date, is to draw on the EU Operations Centre (OPCEN) that was only activated (between March 2012 and December 2016) for coordination purposes of CSDP activities in the Horn of Africa and in the Sahel.

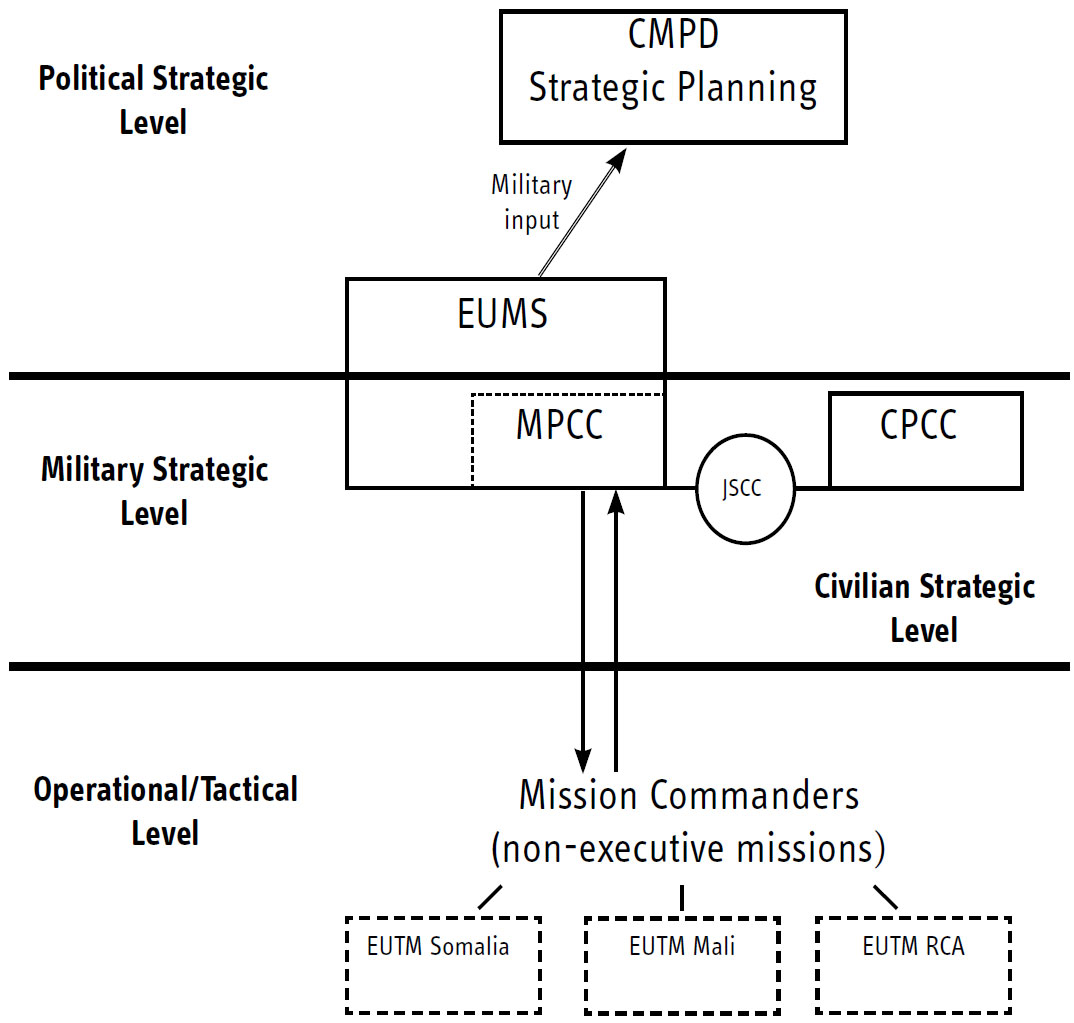

In parallel, in the case of smaller ‘non-executive’ military operations (‘non-executive missions’ are operations that support the host nation with an advisory role only), the option initially preferred was to proceed without an Operation Headquarter (OHQ) at the military strategic level. The military strategic, operational and tactical levels of command were merged, with the in-theatre Mission Commander assuming all levels of responsibility, with the assistance of a Brussels supporting element (within the EU Military Staff [EUMS]). As a consequence, no OHQ was activated for the three existing EU training missions, in Somalia, Mali and the Central African Republic.

The technical and political rationale

The creation of the MPCC has come as the result of three parallel processes, namely the identification of a specific need, the momentum generated by the release of the EUGS, and the UK’s decision to leave the EU. The very idea of an EU standing planning capacity connects to two levels of debate, one of an operational or technical nature, the other a highly political one.

At the operational level, the EU’s dependency from external planning assets has arguably undermined European capacity to plan and run its own operations by itself. The Berlin Plus agreement has become somewhat obsolete and partly also inadequate, and at any rate it is now unlikely to be resorted to. As for national OHQs, their non-standing nature and in any case relative small size have de facto slowed down and constrained EU military activities. The effective activation of the OHQ, together with the designation of an operation commander, can take time. Furthermore, the national character of OHQs gives the country that provides it a disproportionate role in the operation, while distance between the OHQ and Brussels can complicate communication and coordination.

The ad hoc nature of the system also makes it difficult to build up institutional memory on lessons learned and best practices.

In the particular case of non-executive missions, the absence of the military strategic level of command has inherently weakened the missions by depriving them of Brussels-based strategic guidance, especially when those missions have been militarily challenged (as happened for example when the EUTM Mali field HQ in Bamako was attacked in March 2016, incidentally while its Mission Commander was in Brussels). In Brussels the argument goes that non-executive missions may sometimes be even more exposed than the executive ones, therefore calling for stronger support in Brussels. The lack of an OHQ has also shaped the prerogatives and work-load of the Mission Commander, who must both run the mission in situ and report (physically) at regular intervals to Brussels-based Political and Security Committee (PSC), Military Committee, and even ATHENA’s Special Committee.

Those issues have led to calls for some rectification of the initial construction such as the insertion of a military strategic planning and conduct layer (for non-executive missions) within the EEAS.

The political side of the debate is, however, no less salient: indeed, an EU command structure has for years been a symbol of some sort of strategic autonomy. Conversely, for the EU, not having a full-fledged political-military structure has not only been the sign of its incompleteness as a security actor, but also evidence of some member states’ reluctance to see this ever happening. Since the very birth of CSDP, the quest for a military-capable Union has been countered by arguments of non-duplication with existing NATO structures, as well as some more general doubts on whether the EU should take the military route anyway. A permanent OHQ has been at the heart of this opposition. The idea to create such a body was tabled on several occasions, including in the midst of what has remained the most severe crisis of the EU’s CFSP over the Iraq War in 2003, when a group of countries proposed the creation of an EU operational planning cell to remedy the institution’s dependency on third parties. Several other proposals have been put forward since at various levels, notably in relation to the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty – yet a consensus was never reached.

The new momentum

Beyond all this, the release of the EUGS and the momentum it generated, on the one hand, and the perspective of the UK’s leaving the EU, on the other, have created a context in which some sort of permanent command structure has now been contemplated like never before.

The June 2016 EUGS called for the strengthening of ‘operational planning and conduct structures.’ The subsequent Implementation Plan on Security and Defence (SDIP, November 2016) invited member states to ‘review the structures and capabilities available for the planning and conduct of CSDP missions and operations’, and in this context to ‘address the gap at the strategic-level for the conduct of non-executive military CSDP missions from within EEAS structures’. This was taken up by the member states both at Council (November 2016) and European Council (December 2016) levels, where the establishment of the MPCC is formally endorsed, with an implementation deadline set for the first semester of 2017. The MPCC is part of a defence package that includes discussions on, inter alia, permanent structured cooperation (PESCO), the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), but also the creation of a European Defence Fund in the context of the European Commission Defence Action Plan (EDAP).

Given the sensitivities that any debate on an EU permanent planning and conduct structure have revealed in the past, the establishment of the MPCC carries a notable political meaning. The latest negotiations on the shape of the MPCC have highlighted those divergences, with bones of contention including where to locate the MPCC (inside or outside the EUMS), how to designate the head of the MPCC (Director or Commander), and whether the term OHQ can indeed be used in the Council Decisions that will create non-executive missions. Beyond these issues was a concern about how a semi EU military HQ could be perceived in some European constituencies, particularly in relation to member states’ prerogatives in the defence field.

The planning and conduct of non-executive military operations

In any case, the establishment of the new body marks the acceptance that the EU can acquire a proper command capacity itself, something which had been resisted in the past. Whether the MPCC is a one-off measure or a step towards something more ambitious – a permanent OHQ for all military operations – is too early to tell, but a little taboo has been broken, furthermore in a field where advances can only be incremental and slow.

Design and operation

The MPCC is to provide a permanent military planning and conduct capability at the military strategic level for non-executive missions. In the planning phase, the MPCC will draft documents such as the concept of operations (CONOPS), the operation plan (OPLAN) and rules of engagement (RoEs), and will also contribute to the force generation process of the mission. It will then be responsible for the conduct of all non-executive military missions at the strategic (i.e. in Brussels) level.

The MPCC will be part of the EUMS and will be directed by its Director-General (DGEUMS). Formally, the DGEUMS will therefore be double-hatted: in addition to his position as Head of the EUMS, he will assume all responsibilities as Director of the MPCC, and de facto ‘commander’ of all non-executive missions. He will also deal with the ATHENA mechanism that provides common funding for a small share of military operations’ expenses.

The MPCC will roughly be composed of 30 personnel, most of which coming from the EUMS and the de-activated Operations Centre (OPCEN), while less than ten staff members will come as additional resources from the member states (Seconded National Experts).

Initially, there were debates on whether the MPCC should be placed within the EUMS or separately, on a par with its counterpart – CPCC – in the civilian domain. It was finally decided that it should be integrated into the EUMS. The MPCC will nonetheless enjoy the same level of responsibilities than the CPCC does for civilian missions. Coordination with the CPCC is to be assured through a newly-created Joint Support Coordination Cell (JSCC) that will bring together military and civilian personnel so as to maximise synergies between simultaneous military and civilian CSDP missions.

Once in place, beyond strict planning and conduct functions, the MPCC will also take responsibility for issues ranging from reporting to the PSC, EU Military Committee (EUMC) and the Committee of Contributors, civil-military coordination (including with member states and the European Commission), harmonisation of procedures and documents among EUTMs, inter-institutional relations (United Nations, NATO, etc.), to feeding the ‘lessons learned database’ for military operations.

The MPCC is to be reviewed one year after becoming operational, and no later than the end of 2018. Among other issues to be scrutinised by the review are its functioning, efficiency, and positioning within the EEAS crisis management structures, notably in relation with the EUMS and the CPCC.

Implementation first

The MPCC is not the OHQ that some member states would have wished to establish (the very word ‘Headquarter’ was eventually banned), but it is probably as close as it could get to one in the current environment. It comes as a compromise between countries that have pushed for a more ambitious option and those that still resist what they see as either unnecessary or duplicating NATO assets.

In reality, the consensus has been on a relatively modest structure with no budgetary implications for the EU. The MPCC will not require huge additional human nor financial resources. Furthermore, its strict military nature, while projects of a civilian-military structure were dismissed, attests to a limited degree of innovation.

This being said, the unit will need to demonstrate its added-value and the EEAS will be keen to get the transition right. The MPCC’s aim is to ‘improve the EU’s capacity to react in a faster, more effective and more seamless manner’ (Council Conclusions, 14 November 2016). Several issues will have to be closely monitored in this respect.

First is the issue of human resources and whether the 30-staff unit, among which some are double-hatted, including the DGEUMS, is well-calibrated to run the three existing missions (as a comparison, the CPCC counts approximately 75 staff for 9 missions, which means 8-10 persons per mission in both cases).

Second, the reallocation of tasks from the field to Brussels may create tensions at the in-theatre Mission Commanders level that will de facto lose some prerogatives and be placed under the command of the MPCC.

Third, in the longer run is the issue of the role of the MPCC in case non-executive missions are down-sized or even terminated, and how this can shape decision-making on their existence or extension.

Fourth, the civilian-military dimension of CSDP activities together with the newly-framed Integrated Approach imperative will make coordination between the MPCC and the CPCC (through the JSCC) essential. Fifth, the MPCC will deserve decent communication on what it is – and what it is not – so as to defuse any emerging resentment about the counter-productive notion of an ‘EU army HQ’.

Finally, the extent to which the MPCC demonstrates its added-value will inevitably impact the debate about the more ambitious option of a full-fledged OHQ. There is little doubt that this debate will come back with, again, technical arguments pertaining to the operational necessity to have a permanent planning and conduct structure at disposal, and political considerations about what such a capacity would mean for the EU’s quest of a military role, in relation to NATO: la politique des petits pas.

About the Author

Thierry Tardy is a Senior Analyst at the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.