Trust (in) NATO: The Future of Intelligence Sharing within the Alliance

22 Sep 2017

By Jan Ballast for NATO Defense College (NDC)

This article was external page originally published by the external page NATO Defense College in September 2017.1

Introduction

On 21 October 2016, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) appointed its first Assistant Secretary General for Intelligence and Security (ASG-I&S), Dr. Arndt Freiherr Freytag von Loringhoven.2 His appointment was the result of a meeting of the North Atlantic Council (NAC) on 8-9 July 2016 in Warsaw, where the Heads of State and Government stated the requirement to strengthen intelligence within NATO.3 In doing so, the Alliance underlined that improved cooperation on intelligence would increase early warning, force protection and general resilience.4

Freytag von Loringhoven is popularly called the first intelligence chief of NATO. The former German ambassador and Deputy Director of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) is responsible for setting up a new joint intelligence and security division at HQ level. This will merge both military and civilian intelligence pillars, providing intelligence support to the NAC, NATO’s senior political decision-making body, and the Military Committee (MC), the Alliance’s senior military authority. It will also advise the Secretary General (SG) on intelligence and security matters.5

At a special meeting of NATO Heads of State and Government on 25 May 2017 in Brussels, where an action plan to do more in the fight against terrorism was agreed on, it was decided to expand the new division with the establishment of a terrorism intelligence cell. According to the SG this, “[is to] improve the sharing of information among Allies, including on the threat of foreign fighters.”6 With military operations like enhanced Forward Presence on its Eastern Flank and Sea Guardian in its southern waters – confronted with old hybrid adversaries and new asymmetrical wicked problems – bolstering intelligence cooperation within the Alliance clearly answers a genuine concern.

This paper assesses the future of intelligence sharing within NATO following the appointment of the ASG-I&S. It outlines the views of different experts on intelligence cooperation and what sharing of secrets within a multinational organization means. Then it will analyze NATO’s intelligence structure, including previous proposals meant to improve intelligence collaboration. The paper continues by identifying the more challenging aspects of intelligence cooperation facing the ASG-I&S, and his do’s and don’ts concerning structure, sharing and content are discussed. Based on theory, practice and insider knowledge, nine recommendations will be made with the aim of offering Freytag von Loringhoven and his joint division a proposal to enhance intelligence as the first line of defense of the Alliance, with obvious benefits in terms of resilience.

Sharing secrets

To outsiders (counter)intelligence – the (often covert) collection, analysis, sharing and operationalization of sensitive information of military or political value – is shrouded in mystery.7 Non-intelligence personnel always find it hard to fathom why joint operations, return on investment and comprehensive approach leave their intelligence colleagues with eyes glazed over. They are ignorant of intelligence’s obscure characteristics such as trust, risk mitigation, national interest, deception and quid pro quo. For instance, intelligence is a trade-off between trusting a partner enough to share information that could endanger one’s own source, against the benefits of doing so. In the protection of national interest allies are deceived and intelligence cooperation is carefully weighed even with partners (quid pro quo, meaning ‘tit for tat’). This section of the paper outlines why reluctant attitudes to multilateral exchange will remain pivotal in intelligence.

Intelligence is, as a rule, executed by national (civilian, military and hybrid) intelligence and security services that use a combination of intelligence sources to answer Priority Intelligence Requirements (PIRs) of national operational commanders and other decision-making authorities. In the collection process, open sources set the information stage, whereas secret intelligence tends to explain the behavior of the main actors.8 States and their national services are reluctant to share sensitive, classified information with international organizations and favor cooperation on a more controllable, bilateral, case-by-case basis.9 In fact, intelligence is shared only when there is a common threat perception, mutual trust, a demonstrable added value, the right type of diplomatic relationships or a combination of incentives.10 The most successful bilateral secret intelligence collaboration is the Anglo-American UKUSA Agreement, originally signed in 1946, which evolved into the exclusive multilateral so-called ‘Five Eyes’ cooperation.11

Examples of beneficial intelligence cooperation by states within international organizations, such as NATO, are much harder to find. Friedrich Korkisch noted that during the last decades of the twentieth century, intelligence within the Alliance was “the result of the early years of NATO, when it was assumed that all NATO forces would remain under national command, and strategic intelligence would be mainly national intelligence.”12 From the outset Member States shared secret information bilaterally on political and military issues with NATO; however, major countries within the Alliance, afraid of the non-secure Brussels apparatus, kept intelligence from other Members.13 Chris Clough warned that, “within recent military coalitions, intelligence-contributing nations have been mindful of the dangers of compromise by less security-conscious partners, while knowing that a degree of sharing is essential.”14 Some argue that international institutions like NATO play a major role in encouraging and facilitating intelligence sharing among their member states.15 Although, “even in the UN intelligence is no longer a dirty word,”16 others remain of the opinion that nations are unable to overcome mistrust, making them reluctant to engage in multilateral intelligence cooperation.17

The focus of the intelligence world changed profoundly following 9/11 with the emergence of counterterrorism (CT) and non-state actors as dominating global themes.18 Nations witnessed the introduction of collection coordinating mechanisms, such as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) in the United States,19 and target-oriented intelligence fusion centers, such as the Joint Terrorism Analysis Center (JTAC) in the UK.20 Due to the perceived common threat, bilateral exchange of intelligence intensified and alignments were formed even with non-traditional partners. Although this new collaboration with states in Africa and the Near, Middle and Far East resulted in challenges in the realms of oversight and human rights, access to raw data and insights on CT was deemed too relevant not to engage – ‘gains’ outweighed ‘risks’.21 Following the terrorist attacks on major European cities, cooperation between the security services deepened and nations realized that solidarity as well as sharing intelligence on CT should be the norm.22

On a multilateral level, NATO, lacking its own sources by design, responded by introducing intelligence liaison and fusion elements and reaffirmed its commitment to intelligence sharing.23 However, different languages, cultures, capabilities and infrastructures proved to be structural constraints.24 Unlike the Alliance, the leadership of the European Union (EU) claimed a coordinating role in support of all state-level courses of action on CT through a combination of its law enforcement agency Europol, judicial cooperation agency Eurojust and border management agency Frontex.25 The EU, not questioning state actors as first responders to terrorism and its related criminal networks, strengthened its intelligence structure and joint multilateral intelligence collaboration was suggested.26 John Nomikos noted that “while Belgium, [The Netherlands] and Austria demanded a CIA-style EU agency, powerful member states including Britain, Germany, France, Spain and Italy showed a reluctance to share intelligence.”27 Following the Paris 2015 attacks, German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière shattered Belgian, Dutch and Austrian dreams; “We should not focus our efforts on creating a new European intelligence service now. I cannot imagine we will be willing to give up our national sovereignty.”28

Intelligence within the Alliance

This section discusses intelligence structures within NATO pre-2016 and previous attempts to improve its intelligence cooperation. Prior to 9/11, intelligence originating from UKUSA/’Five Eyes’, was dominant within the Alliance and other Member States relied on it in times of trouble. This information would not automatically be shared, however, due to mistrust of new Allies and insecure dissemination and storage facilities.29 The United States, primus inter pares within the ‘Five Eyes’ community, was instrumental in establishing common procedures and terms which facilitated intelligence sharing,30 but, as Jennifer Sims pointed out, ”the quality of the exchange will generally be determined by the least trusted (most suspected) member of the group.”31 As a result of politicization, decentralization and a lack of common culture and trust, the Americans – and British – never truly believed in the Alliance as a multinational intelligence cooperation platform.32 Moreover, the United States, reassured by its experiences during the 1999 Kosovo Crisis, saw no need to strengthen NATO’s intelligence structures. According to Wesley Curtis, “thanks in large part to its satellites, superior UAVs [Unmanned Aerial Vehicle] and reconnaissance and surveillance aircraft, the United States met approximately 95 [percent] of NATO intelligence requirements [on Kosovo].”33

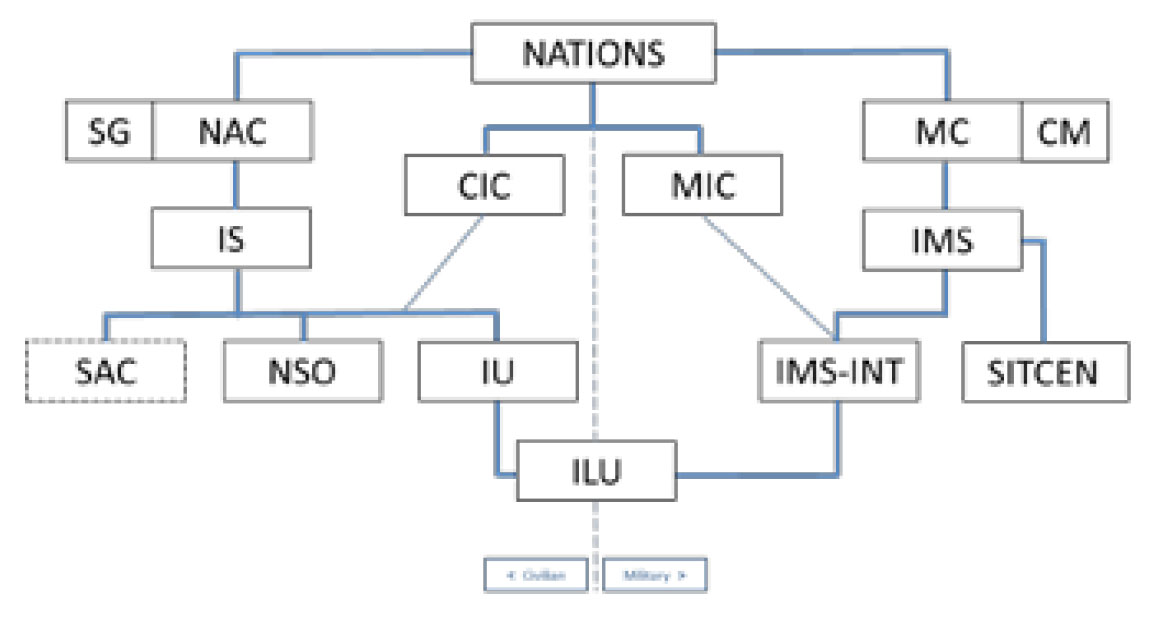

Strategic level

Until the appointment of the ASG-I&S in October 2016, political-strategic intelligence in NATO HQ was divided between civilian and military pillars, despite the Alliance already agreeing in 2004 in Istanbul to “a review of current intelligence structures.”34 Not only the official NATO structures, but also the intelligence and security services of the Member States, acting as independent bodies, were from the outset organized accordingly. For the civilian side, national security and hybrid services joined together in the Civilian Intelligence Committee (CIC, with the NATO Special Committee as its forerunner), whereas the national military intelligence and hybrid services made the Military Intelligence Committee (MIC, formerly known as the NATO Intelligence Board) their platform. Consequently, the informal yearly Joint CIC/MIC November Plenary brought almost eighty representatives to the table. What is more, according to a senior staff member, there were several instances where the CIC and MIC representatives from the same Member State openly disagreed at the table.35 This did not improve intelligence sharing substantially, maybe even hindered it.

On the civilian side, the International Staff (IS) in Brussels accommodated the Intelligence Unit (IU), founded in 2011 following a request from the SG. In principle, IU reported to the NAC and in copy to CIC. CIC, chaired by the nations on an annual rotating basis was responsible for matters of espionage and terrorist or related threats. In its day-to- day work, it was supported by the NATO Office of Security (NOS),36 IS’ counterintelligence agency, which advised the SG and the Security Committee (SC) on security concerns and policy matters.37 The Intelligence Division (INT) of the International Military Staff (IMS), known as IMS-INT, reported to the MC and in copy to MIC. The civilian IU and the military IMS-INT would both draft non-agreed intelligence reports on a daily basis, including strategic foresight, and provide intelligence support to all NATO HQ elements, NATO Member States and NATO Commands. IMS-INT also exclusively provided NATO-agreed strategic early warning – the so-called NATO Intelligence Warning System (NIWS) – and situational awareness – General Intelligence Estimate (NSIE) or MC-161 series – to all NATO HQ entities and nations.38 Finally, the Situation Center (SITCEN), embedded in IMS at HQ level, provided 24/7 current intelligence from open sources and spot reports.

The global terrorist threat and the Alliance’s engagement in CT-inspired military missions resulted in the growing importance within NATO of intelligence sharing on terrorism. As a consequence, in 2003 the Terrorist Threat Intelligence Unit (TTIU) was created at HQ,39 followed by the joint IS/IMS Intelligence Liaison Unit (ILU) for the exchange of information with non-NATO partners.40 In 2010, the NAC agreed to establish the Emerging Security Challenges Division (ESCD); ESCD was intended to address a growing range of non-traditional risks and challenges, focusing on CT, cyber defense, Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) and energy security.41 In the process, ESCD’s Strategic Analysis Capability (SAC), drafting reports based on open source, diplomatic reports and intelligence, evolved into another HQ assessment asset. SAC, with cyber and so-called science-for-peace as its main priorities, also risked overlap with IMS-INT’s NIWS, NATO’s early warning tool for (un)known unknowns.

Figure 1. NATO HQ intelligence pre-2016

NATO’s Brussels-based political-strategic agencies are connected to Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), located in Mons, Belgium. SHAPE is the military-strategic level HQ of Allied Command Operations (ACO) and responsible for the planning and execution of all NATO operations.42 Consequently, Mons provides guidance to its subordinate organizations, including its Joint Force Commands (JFC) and multinational units on NATO’s Eastern Flank.43 The J2 Division of SHAPE, reporting to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Intelligence (DCOS OPI), is tasked with operational intelligence production and contributing to the development of ACO’s intelligence policy, as well as providing (counter)intelligence and security advice to its overall commander, SACEUR.44 The intelligence division became an integral part of the Comprehensive Crisis and Operations Management Centre (CCOMC), which SHAPE in 2012 decided to create to analyze developing crisis situations and be ‘NATO’s Military Eye’ on the world.45 As such, J2 Division contributes to the comprehensive assessments for strategic awareness provided by CCOMC, SHAPE’s innovative fusion center conceived to break down stovepipes. In Mons, the 650th US Military Intelligence Group/Allied Counterintelligence Activity deals with day-to-day counterintelligence, which includes counterespionage and the protection of SHAPE’s key personnel, resources and critical infrastructure.46

Operational level

Aiming to correct mistakes during the Balkan Wars and in support of ongoing operations in Afghanistan, Allied Command Transformation (ACT) determined that NATO should adapt in order to meet future operational (and tactical) intelligence needs.47 Based on the commitment displayed during the Prague Summit of 2002, the NATO Intelligence Fusion Center (NIFC) was created in Molesworth, UK, in 2006, allowing Member States to jointly develop, fuse and share information.48 For the United States, as framework nation and main provider of both classified and the best available open source information, NIFC served to invest in non-US personnel, incorporate intelligence input from Member States and produce non-agreed all-source intelligence.49 The driving force behind NIFC was Gen James Jones (SACEUR 2003-2006), who acknowledged that the agency, under the auspices of DCOS OPI, remained outside national and international command structures, while at the same time supporting SHAPE’s J2 Division and CCOMC.50 As such, (elements of) NIFC could be forward deployed or provide reach-back for deployed NATO forces, while at the same time producing draft intelligence reports for NATO and the nations.

At the Chicago Summit of 2012, the Alliance launched the Joint Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) initiative. Four years later in Warsaw, NATO leaders expressed their intention to promote intelligence sharing beyond JISR, by using and optimizing NATO and other multinational platforms and networks.51 In June 2016, a rewarding JISR exercise was conducted with 400 participants from seventeen Member States, working from ten different locations. It was concluded that the 2016 edition of Unified Vision, managed by ACT and NATO HQ, had improved the Alliance’s ability to share and process complex operational intelligence aimed at supporting commanders of multinational units.52 Although the exercise included the use of valuable national assets such as UAVs, whether Member States in future will share critical national information or are prepared to provide insight into their national modus operandi is yet to be determined.

Mission commanders and intelligence experts have concluded that the intelligence provided during recent NATO operations lacked the strategic dimension. Maj Gen Michael Flynn experienced the inability to include cultural, social and demographical aspects to combat the Taliban in Afghanistan.53 He quoted Gen Stanley McChrystal, stating that “the conflict will be won by persuading the population, not by destroying the enemy.”54 US Army Lt Gen Mark Hertling (ret) judged the information on the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) too narrow and target-oriented, whereas ‘big-picture’ intelligence on how to tackle ISIL and understanding its global impact was equally important.55 This is even more so following the warning by Gen John Allen, the former US Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL, that ISIL views the coalition (including NATO) as an “existential threat” and Europe as the battleground for its counterattack.56 Concerning Libya, Adam Svendsen noted the deployment of Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) tools alongside prioritized target acquisition, to provide “effective situational and battlespace awareness concerning Gadaffi’s forces.”57 However, the slow release of actionable intelligence during the air campaign in Libya created mistrust between France and the United States, once more underlining NATO’s problematic intelligence sharing apparatus.58

The agreement at the Warsaw Summit in 2016 to create the position of the ASG-I&S was the fulfillment of a long-cherished American wish.59 Based on best practices from recent military missions, coordination in (and from) Brussels was thought to be instrumental in synchronizing NATO’s strategic and operational intelligence structures. First and foremost, however, it served to address the United States’ annoyance with the many different and inefficient intelligence agencies within the Alliance. Although the appointment of the new intelligence chief by no means implied the start of unrestricted American information sharing with NATO, it was argued that the ASG-I&S, owing to his level and mandate, would put earlier coordination efforts in the shade and surely improve the cooperation between the civilian and military intelligence pillars in HQ. This section deals with the ASG-I&S’ priorities, the positioning of his new unit, and his “do’s” and “don’t’s.”

NATO’s intelligence future

On 12 April 2017, the importance of the new position of the ASG-I&S was illustrated when Freytag von Loringhoven was the only ASG to join the SG on his first visit to US President Donald Trump. However, although NATO’s intelligence chief is an influential person within the Alliance, his Deputy, US Brig Gen Paul Nelson, told him upon arrival at the end of 2016 that he would have access to NATO releasable information only and not to all US intelligence.60 Intelligence is the first line of defense and therefore instrumental in making the Alliance and its Member States more resilient. The ASG-I&S will need to address the future structure, sharing procedures and content of NATO intelligence.

Structure

Inspired by interviews with (American ex-) senior staff members of the Alliance, Brian Foster in 2013 pleaded for enhanced efficiency and improved quality of NATO’s intelligence. He suggested the creation of an Assistant Secretary General for Intelligence (ASG-I) who should be tasked with overseeing and ultimately merging IU, IMS-INT and SAC, thus putting an end to duplication, over-tasking and competition in Brussels.61 Foster claimed that, “[IMS-INT, IU and SAC] work on 75 [percent] of the same topics with only slight variations of focus.”62 Others also stressed the need to change NATO’s intelligence structure, arguing that enhanced coordination would lead to more timely and accurate information.63 Thus – maybe except for some intelligence bureaucrats in Brussels who may have hoped the intentions of the Istanbul 2004 Communiqué would have been forgotten – the appointment of Freytag von Loringhoven in 2016 as the first ASG-I&S was welcomed across the board.

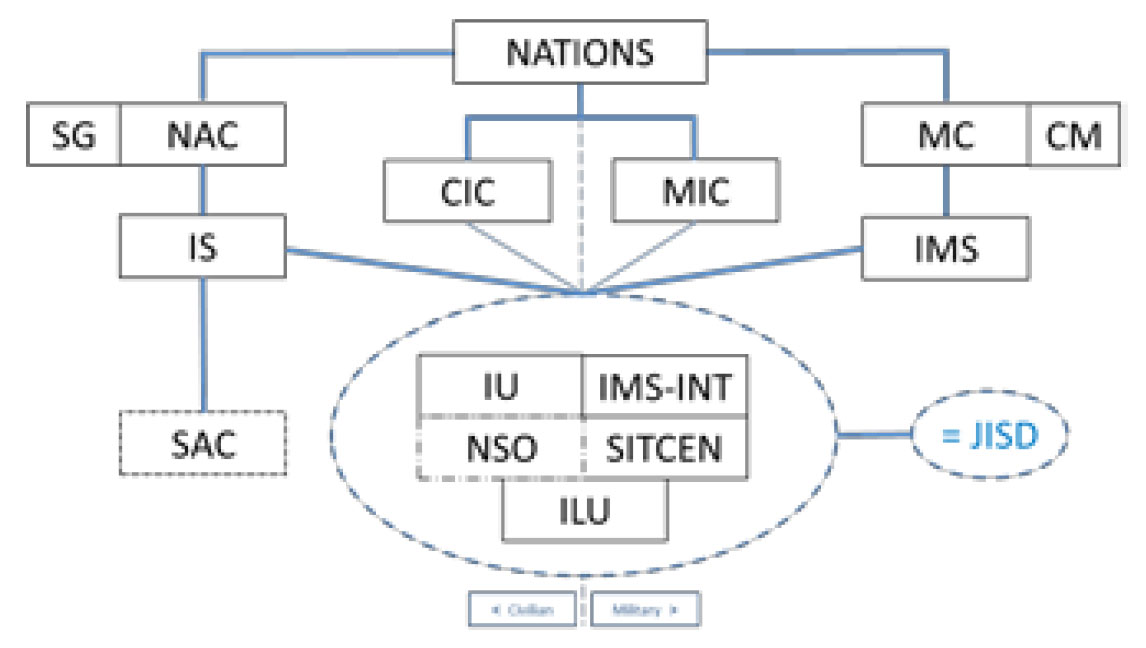

The ASG-I&S has already started to transform NATO’s HQ intelligence structure into the new Joint Intelligence and Security Division (JISD). In April 2017, the Assistant Secretary General on Emerging Security Challenges (ASG-ESC), Amb Sorin Ducaru, applauded the ASG-I&S for merging military and civilian intelligence into JISD. While the implementation of the new unit is still a work in progress, he observed that IU and IMS-INT no longer distributed the same reports, but that fused intelligence was now being received. Ducaru added that to avoid duplication, programs and themes were being closely coordinated between ESCD/SAC and JISD and that from his perspective as a consumer, positive results were visible.64 However, the incorporation of SAC into JISD remains a logical next step, as this would enrich the ASG-I&S’ intelligence and early warning products, as well as further excluding duplication of activities. Ducaru predicted that “a merger of [the military] MIC and [civilian] CIC is possible, [but] closer cooperation with SHAPE is more difficult, due to different cultures.”65

Within the JISD the merger has resulted in a clash between the civilian and military intelligence pillars.66 Although this is a normal reaction to an interagency fusion process due to cultural differences, a fundamental discussion about security continues to challenge the ASG-I&S. The bottom line is that concepts like ‘domestic, security, risk’ can be used to typecast CIC/IU, and its representatives adhere to the ‘need to know’ principle, whereas the culture of MIC/ IMS-INT is characterized by ‘foreign, intelligence, gain’ while its exponents favor the ‘need to share’ approach. “It is confidence building between two entities that have different strings of DNA,” according to a senior staff member.67 Some of CIC’s national civilian services find it unacceptable that the military are sharing intelligence on the Baltic region with non-NATO members Sweden and Finland, whereas the military from an operational perspective view this cooperation as justified and necessary. Furthermore, the Romanians in CIC lead the move to shelve the allegedly unsafe Battlefield Information Collection and Exploitation System (BICES), NATO’s basic military intelligence sharing technology.

Unlike the uncontroversial absorption of HQ’s small partner liaison element ILU, some services within CIC are not convinced that the temporary integration of the counterintelligence agency into JISD should obtain permanent status; it is contended that its unique features would not be sufficiently preserved and thus NOS should once more be independent and report to CIC. The tasking of the terrorism cell in JISD could add fuel to this fire, for the issue of foreign fighters is controversial to national civilian and military services. Domestic civilian security services claim responsibility because of the threat returning foreign fighters pose to their home countries, whereas military foreign intelligence services argue for a lead role due to the risk for national forces deployed in mission areas. This controversy does not bode well for the positioning of the terrorism cell within JISD. However, if NATO should focus on foreign fighters and terrorism as a threat to deployed forces in theaters of operation and leave homegrown terrorism and domestic threats to state actors and the EU, the preparedness to share intelligence within the Alliance might increase.

Figure 2. NATO HQ intelligence post-2016

Besides different cultures, NATO HQ and SHAPE have different mandates that make a merger of both intelligence structures less desirable. A more centralized entity at HQ level should not evolve into a bureaucratic directorate jeopardizing military interests at strategic and operational level. Military experts seem especially reticent about too radical changes to NATO’s intelligence structure. According to a German staff officer, an intelligence merger should not endanger military priorities and the MC and its Chairman as an independent tasking authority; “Germany prefers getting better access to already existing information. We do not need a large central staff or regional intelligence centers. [NIFC at] Molesworth can collect and provide.”68 The ASG-I& S should settle for investing in permanent liaison officers between his JISD and SHAPE’s J2 Division to stimulate transparency. As such, he would create good insight into what Mons is doing and vice versa. Finally, Freytag von Loringhoven should coordinate the activities of HQ and SHAPE with DCOS OPI, making sure that JISD principally deals with political-strategic intelligence and J2 Division exclusively with military-strategic intelligence. General information should be shared simultaneously between both agencies, including NIFC, without reservations.

The ASG-I&S’ first priority, therefore, should be the implementation of the merger of all intelligence elements at HQ level into an effective JISD. Freytag von Loringhoven could accomplish this in his talks with the chair of CIC and MIC, who as a trio recently started meeting on an almost regular basis.69 In order to be efficient, the ASG-I&S should be given the mandate to coordinate all intelligence activities at HQ level to avoid duplication of NATO’s scarce capacity. Currently, at least three agencies at NATO HQ are more or less involved in strategic foresight, and the same three also deal with aspects of strategic early warning. As discussed earlier, a merger of JISD, NOS and ESCD/SAC, the three duplicating agencies identified, not only seems a logical one but should be implemented without further delay. The less preferred option is the continuation of SAC as an analysis entity without the use of intelligence – making it a paper tiger – whereas the renewed separation of NOS would resurrect the two intelligence pillars and breed discord.

Sharing

To be successful, the ASG-I&S should not try to convince Member States to start sharing sensitive, classified intelligence. Being himself a former Deputy of the BND, he will know that Member States and their national intelligence and security services are by nature reluctant to share secrets within NATO. Jennifer Sims already predicted the outcome of such pressure; “If “jointness” [in intelligence] is driven more by political necessity than collection requirements, liaison will tend to be heavily defensive in posture, implicitly adversarial, and therefore hollow, despite political and military leaders’ contrary expectations.”70 For instance, although France is likely to cooperate on intelligence if strategic interest is shared and if mutual boots are on the ground,71 it remains unsympathetic to integration and cooperation within any multilateral environment. A senior official of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs explained that France would always want to preserve its strategic autonomy.72 In sum, the second priority for the ASG-I&S should be accepting the continuation of bilateral arrangements between NATO and its Member States.

Notwithstanding the prominent position of major European nations, the ASG-I&S as his third priority should acknowledge a dominant role for the United States. The United States is not only the Member with the most (operational) intelligence to share, but it will also be crucial in facilitating (future) technological infrastructure to enable the exchange process. If the United States does not bridge the technological gap within the Alliance, NATO’s interconnectivity and interoperability will be at risk.73 Air operations and Joint Special Operations (JSO) especially require the right infrastructure to achieve effective sharing and dissemination of actionable and time-sensitive intelligence to maintain information dominance.74 Meanwhile, the ASG-I&S should invest in and expand existing enablers such as the underused BICES,75 in close cooperation with SHAPE/NIFC, embracing best practices from missions like joint databases and the Afghan Mission Network (AMN).76 In the process, he should safeguard reciprocity and intervene if information is one-way, as is the case with CT – namely to and not from the United States.77

Should Freytag von Loringhoven want to address other constraints of multilateral intelligence sharing such as over-classification, disclosure and oversight as his fourth priority, he needs to get the United States on board to solve. In 2011, the Inspector General of the US Department of Defense recommended an update of the US disclosure policy and procedures concerning sharing of intelligence in a coalition environment.78 At the same time, the ASG-I&S should insist, regardless of CIC/NOS, that SC tackles over-classification as per NATO’s security policy and strives for the widest dissemination possible. As Adriana Seagle observed, “Though a necessary security capability in the 21st century networked world, the shift from “need to know” to “need to share” has not been smooth.”79 Besides consensus on internal sharing, the United States and other Member States will also need to consider the usefulness of increased intelligence cooperation with the EU. Finally, NATO’s role in the growing international intelligence exchange raises the question of democratic accountability and calls for multinational (administrative) oversight.80 It would appear that the ASG-I&S, on behalf of the Member States, is the best alternative for addressing this liability within the Alliance.

As his fifth priority, the ASG-I&S should develop sharing as a process, slowly bridging the gap between bilateral, case-by-case liaison and structured multilateral intelligence sharing. As already discussed above, he should continue to accept existing bilateral and multilateral cooperation within the Alliance. Coalitions of the willing, able, likeminded and trusted should be allowed, based on NATO’s core tasks, to form communities of interest – already technically facilitated by BICES – and start an association process respecting ‘need to know, need to share’ and excluding ‘nice to know’. Chris Clough warned, “Alliances and coalitions have traditionally been weak in terms of intelligence: as the number of partners increases, so the level of guaranteed security decreases.”81 Although these topic- and mission-oriented coalitions would still depend on the willingness of individual Member States to share intelligence,82 the chances of successful cooperation would increase because it is easier for a few Allies to collaborate and find common ground than for NATO as a whole. Examples of such ad hoc alliances did materialize in Afghanistan and the Middle East, with secure communication and information systems as a key enabler. Preferably, JISD or SHAPE J2 Division/NIFC could take on a coordinating role in such future communities of interest.

Content

The fact that NATO has no consensus definition of its threat environment, nor a ranking list of its priorities, complicates the ASG-I&S’ task. Earlier, terrorism, mission support, counterespionage and Russian hybrid warfare activities were identified as his main areas of concern.83 More recently, the foreign fighters’ threat was specifically added.84 However, even on agreed threats there are fundamental differences of opinion within the Alliance. Adriana Seagle acknowledges that “whereas the United States and UK deal with terrorism in the military realm, allies belonging to the EU address terrorism in the domain of law and crime prevention.”85 Conflicting interests of Member States imply that the ASG-I& S, as his sixth priority, should balance intelligence on all the three core tasks of NATO. In the realm of collective defense, Russia and its hybrid (cyber inclusive) warfare remains his main intelligence focus, whereas in the domain of cooperative security, military support to countering terrorist threats is his central theme. Concerning crisis management, the ASG-I&S has to concentrate on (potential) military missions abroad preventing or fighting terrorism and operations mitigating or in assistance of refugee and migration (humanitarian) crises.

Absence of a clear and present danger results in national secrets not being shared with NATO, while a rapidly changing world with wicked and immediate problems necessitates improved early warning to enhance resilience. Confronted with non-state actors and (un)known unknowns such as nanotechnologies, cybernetic organisms, biological agents and energy security, timeliness and ‘jointness’ is essential. Therefore, Freytag von Loringhoven should further develop open source capability within NATO and invest in social media analysis and exploitation.86 As Lt Gen Samuel Wilson, former Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), stated, “Ninety percent of intelligence comes from open sources. […] The real intelligence hero is Sherlock Holmes, not James Bond.”87 Fusion of open source and social media analysis with existing intelligence from other disciplines guarantees all-source available products. This should be the ASG-I&S’ seventh priority and is especially relevant for strategic foresight and early warning. In the process, JISD should closely cooperate with SHAPE/NIFC and copy best practices especially from the All Source Intelligence Centre (ASIC), which was instrumental in the fusion of innovative and actionable ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence on Afghanistan.88

Although it is highly unlikely that NATO will ever adopt the full, free and open data access policy of the European Space Agency (ESA), the high-resolution imagery of up to 10 meters provided by ESA is a perfect example of valuable open source information. Although it is not the same quality as the Very High Resolution (VHR) secret products from military satellites (up to 30 centimeters), for NIFC in Molesworth and non-NATO entities such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and EU’s Frontex, the ESA data is already an important asset.89 Indeed, NATO could thus use open sources to counter information operations in the hybrid warfare domain. In the near future, full access to live streaming videos from space, already available from ESA’s Sentinels, but not yet openly accessible,90 could be a crucial next step in intelligence fusion within the Alliance, while at the same time giving NATO’s (non-state) adversaries advantages unheard of before.

In association with DCOS OPI, the ASG-I&S should support balanced all-source intelligence for commanders and other decision makers. As studies on NATO’s support of recent missions have underlined, operations are in need of target-oriented actionable intelligence as well as strategic ‘big-picture’ information. Therefore, the eighth priority for Freytag von Loringhoven is to make JISD, once it receives relevant information, supportive of the military-strategic and operational intelligence efforts of the Alliance. The ASG-I&S and DCOS OPI should strongly advocate intelligence cooperation in operational missions, where lifesaving actionable intelligence matters more than controversial national strategic interests. On issues like force protection, maximal exchange of information at all levels, coordinated by communities of interest, must be the norm. Stewart Webb, acknowledging that “intelligence sharing is the ultimate demonstration of trust and interoperability,”91 suggested that prior to a new mission, nations should provide intelligence caveats to NATO, while in theatre intelligence specialization should be considered.92 In general, inter-NATO understanding abroad would be enhanced through genuine multilateral training of intelligence personnel and systems.

Ultimately, success or failure of the ASG-I&S is subject to the relevance of his intelligence products to the consumers. Lars Nicander wrote, “Intelligence is only as good as the value assigned to it by the users.”93 Similarly, Björn Fägersten called for more interaction between policymakers and intelligence analysts, while pointing out that “[in the end] effective intelligence support is dependent on the clear vision of what is to be supported.”94 Close(r) interaction with the consumers of intelligence – as long as non-politicized intelligence is the outcome – will improve the perception of timeliness, accuracy and reliability (reputation), as well as the weighing of the ready availability, ease and flexibility of use and comprehensiveness (precision) of the products.95 Therefore, the ASG-I&S’ ninth priority should be to build bridges between consumers and producers, starting with the coordination and interpretation of the former’s requirements. To help accomplish this task, Member States should send professional career intelligence officers to JISD or the ASG-I&S should be allowed to self-hire. In addition, academic outreach (through seminars) and interaction with think tanks would be beneficial. Collection is meaningless without analysis, since it is not the collection, but the analysis that creates value.

Conclusion

Do NATO Member States trust each other enough to cooperate on intelligence and do the national intelligence and security services trust their Alliance and its new intelligence chief to successfully manage the sharing of intelligence? Richard Aldrich was skeptical, “States will happily place some of their military forces under allied command, but hesitate to act similarly in the area of intelligence, where coordination rather than control is the most they will accept.”96 Multinational intelligence cooperation will always be characterized by issues such as lack of a common threat perception, national interest, culture and (political dis)trust and consequently, national services are unlikely to share with NATO as a whole and prefer bilateral arrangements. Any Member State is first a state and then a member. As long as nations are unable to multilaterally share secret intelligence on (homegrown) terrorist groups and threats, NATO, without a clear and present danger, will not witness structured and transparent intelligence sharing; open source exchange being the exception.

Whether the ASG-I&S will succeed in creating a joint all-source intelligence structure and thus oversight, will depend largely on the ability of the national intelligence and security services to adopt a constructive attitude in relation to this assignment. The fundamental differences of opinion between the civilian and military pillars in Brussels – CIC vs MIC – are a mirror image of the Member States, where services instinctively are in competition rather than cooperating. The fact that the emergence of CT and hybrid (cyber inclusive) warfare has blurred the boundaries between ‘foreign intelligence’ and ‘domestic security’ collection, as well as between traditional civilian and military intelligence, not only enhances connectivity, but also challenges the services’ raison d’être as well as their esprit de corps. Although the merger of civilian/military and security/intelligence is a controversial one, the ASG-I&S’ ultimate success – dependent on his empowerment by the Member States and NATO – could set an example for nations and other organizations to follow.

To be successful, the ASG-I&S will have to continuously address the future structure, sharing and content of NATO intelligence. His main focus should be on structure and strive to (1) merge all intelligence entities at HQ level into JISD, removing discord and duplication, while at the same time refrain from trying to integrate intelligence structures of NATO HQ and SHAPE.

In order to succeed with regards to sharing, the ASG-I& S should (2) accept the continuation of bilateral arrangements between NATO and its Member States, without pressuring nations into sharing national secrets. In doing so, he should (3) acknowledge the lead nation role for the United States on intelligence, including its administering of a secure, technologized common sharing infrastructure for the Alliance. In coordination with the United States, he should (4) address constraints in multilateral intelligence sharing such as over-classification, disclosure and oversight. Simultaneously, but incrementally, the ASG-I&S should (5) invest in bridging the gap between bilateral, case-by-case liaison and structured multilateral sharing, by allowing coalitions of the willing, able, likeminded and trusted to form (topic- or mission-oriented) communities of interest.

Content-wise, the ASG-I&S should (6) balance all-source intelligence on all the three core tasks of NATO, and at the same time (7) promote the use of fused open source and social media analysis for strategic foresight and early warning exploitation purposes thus enhancing resilience. His JISD should (8) support, if circumstances so require, the military-strategic and operational intelligence efforts of the Alliance. Ultimately, the success or failure of the ASG-I&S depends on his added value, so he should (9) strive to provide intelligence products relevant to the consumers.

Intelligence is the Alliance’s first line of defense for all three of NATO’s core tasks. Confronted with (un) known unknowns, improved intelligence sharing allows NATO to be more resilient and enables the Alliance to identify at least some unknowns. Therefore, Member States should trust in NATO more and trust the ability of the ASG-I&S to coordinate and further develop the process of intelligence cooperation. Consequently, if he observes the nine recommended priorities, he should receive the outright support of all national intelligence and security services of the Member States, as well as the Alliance’s independent intelligence bodies CIC and MIC. This will allow him to strengthen and optimize NATO’s intelligence collection, analysis and dissemination process. If thus supported, the ASG-I&S could set the stage for a future where, if the right conditions prevail, more secret intelligence will be shared within the Alliance.

Notes

1 Jan Ballast MA is a senior staff member, involved with foreign intelligence, mission support and national security, working for the Ministry of Defence of The Netherlands. He has held numerous analytical and operational positions in both The Hague and missions abroad. The views expressed here are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Government of The Netherlands or any of its departments or agencies. An earlier version of this article was presented at the NATO Defense College, Rome, Italy, in May 2017. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of NATO or the NATO Defense College.

2 “Deutscher wird erster Geheimdienst-Chef der NATO,” RP Online, 21 October 2016. Accessed at http://www.rp-online.de/politik/ausland/deutscher-arndt-freytag-von-loringhoven-wird-erster-geheimdienstchef-der-nato-aid-1.6342986 on 13 May 2017; Julian Barnes, “NATO Appoints Its First Intelligence Chief,” Wall Street Journal, 21 October 2016. Accessed at https://www.wsj.com/articles/nato-appoints-its-first-intelligence-chief-1477070563 on 13 May 2017.

3 “Warsaw Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw 8-9 July 2016, 09 Jul. 2016, Press Release (2016) 100.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm on 13 May 2017.

4 Ibidem; Jamie Shea, “Resilience: a core element of collective defence,” NATO Review Magazine, 2016. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/docu/review/2016/Also-in-2016/nato-defence-cyber-resilience/EN/index.htm on 13 May 2017.

5 “Ex-BND-Vize übernimmt Geheimdienstposten bei NATO,” n-tv, 24 October 2016. Accessed at http://www.n-tv.de/ticker/Ex-BND-Vize-uebernimmt-Geheimdienstposten-bei-Nato-article18921376.html on 13 May 2017.

6 “NATO leaders agree to do more to fight terrorism and ensure fairer burden sharing,” 25 May 2017, NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_144154.htm on 25 May 2017.

7 (Counter)intelligence is about acquiring ‘decision advantage’ by getting better information for one’s strategy than one’s opponents gain for theirs, or by degrading the competitor’s decision-making through denial, disruption, deception, or surprise. The latter category of activity is called counterintelligence. See: Jennifer Sims, “Intelligence to counter terror: The importance of all-source fusion,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2007, p. 40. In this paper, no differentiation is made. For the definition see: GLOBSEC Policy Institute, GLOBSEC Intelligence Reform Initiative. Reforming Transatlantic Counter-terrorism, Bratislava, GLOBSEC Policy Institute, 2017, p. 6.

8 The basic collection disciplines are the following: Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT), Human-Source Intelligence (HUMINT), Imagery Intelligence (IMINT), Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) and Signals Intelligence (SIGINT). See: “What is Intelligence?” Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Accessed at https://www.odni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/what-is-intelligence on 14 May 2017. Also, Acoustic Intelligence (ACINT), Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT) and Medical Intelligence (MEDINT) were added, see: James J. Wirtz and Jon J. Rosenwasser, “From Combined Arms to Combined Intelligence: Philosophy, Doctrine and Operations,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 25, No. 6, 2010, pp. 730-739; Ministerie van Defensie, Joint Doctrine Publicatie 2 “Inlichtingen” (JDP-2) (Den Haag: Ministerie van Defensie, 2012), pp.76-82. More recently, Cyber Intelligence/Digital Network Intelligence (CYBINT/DNINT), Financial Intelligence (FININT), Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) and Technical Intelligence (TECHINT) were identified.

9 Stéphane Lefebvre, “The Difficulties and Dilemmas of International Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2003, pp. 527-529; Joseph W. Wippl, “Intelligence Exchange Through InterIntel,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 25, No. 11, 2012, p. 8.

10 Lefebvre, “The Difficulties and Dilemmas,” pp. 528-529; Chris Clough, “Quid Pro Quo: The Challenges of International Strategic Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2004, pp. 603-605; Cees Wiebes, “De problemen rond de internationale intelligence liaison,” Justitiële Verkenningen, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2004, pp. 79-80; Derek S. Reveron, “Old Allies, New Friends: Intelligence Sharing in the War on Terror,” Orbis, Vol. 50, No. 3, Summer 2006, pp. 456-457; Monica Den Boer, “Counter-Terrorism, Security and Intelligence in the EU: Governance Challenges for Collection, Exchange and Analysis,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 30, No. 2-3, 2015, p. 404; Jonathan N. Brown and Alex Farrington, “Democracy and the depth of intelligence sharing: why regime type hardly matters,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2017, p. 68.

11 See for the UKUSA Agreement between the First Party (the United States) and Second Parties (the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand): Richard J. Aldrich, “British Intelligence and the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’ during the Cold War,” Review of International Studies, Vol. 24, No. 1, March 1998, pp. 331-351; James Igoe Walsh, The International Politics of Intelligence Sharing New York: Columbia University Press, 2009, pp. 31-44; Adam D. M. Svendsen, Intelligence Cooperation and the War on Terror: Anglo-American Security Relations After 9/11, London and New York, Routledge, 2010.

12 Friedrich W. Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence: New Challenges Require New Answers to Satisfy Intelligence Needs for Headquarters and Deployed/Employed Forces,Vienna, IAS, 2010, p. 8.

13 Clough, “Quid Pro Quo,” p. 604; Walsh, The International Politics, pp. 47-48; Don Munton and Karima Fredj, “Sharing Secrets: A Game Theoretic Analysis of International Intelligence Cooperation,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2013, p. 673.

14 Clough, “Quid Pro Quo,” p. 602.

15 Simon Duke, “Intelligence, security and information flows in CFSP,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2006, p. 624; Adam Svendsen, “The globalization of intelligence since 9/11: Frameworks and operational parameters,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2008, p. 133; Martin J. Ara, Thomas Brand and Brage A. Larssen, Help A Brother Out: A Case Study in Multinational Intelligence Sharing, NATO SOF, Monterey: Naval Postgraduate School, December 2011, p. 45; Adriana N. Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices Within NATO: An English School Perspective,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2015, p. 569.

16 Briefing by Maj Gen Adrian Foster (UK), UN Deputy Military Adviser, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, UN HQ, New York, 11 May 2017.

17 Lefebvre, “The Difficulties and Dilemmas,” p. 537; Richard J. Aldrich, “Transatlantic Intelligence and Security Cooperation,” International Affairs, Vol. 80, No. 4, 2004, p. 737; Clough, “Quid Pro Quo,” p. 612; Björn Fägersten, “For EU eyes only? Intelligence and European security,” European Union Institute for Security Studies, Brief No. 8, March 2016, pp. 2-3.

18 Walsh, The International Politics, pp. 110-131; Patrick F. Walsh and Seumas Miller, “Rethinking ‘Five Eyes’ Security Intelligence Collection Policies and Practice Post Snowden,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2016, p. 357.

19 See: John A. Gentry, “Has the ODNI Improved U.S. Intelligence Analysis?” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2015, pp. 637-661, especially p. 637.

20 Lars D. Nicander, “Understanding Intelligence Community Innovation in the Post-9/11 World,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2011, pp. 534-568, especially p. 561.

21 Reveron, “Old Allies, New Friends,” pp.462-467; Walsh, The International Politics, pp. 121-128; Adam D.M. Svendsen, “Developing International Intelligence Liaison Against Islamic State: Approaching “One for All and All for One”?” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2016, pp. 265-268.

22 Civilian security services cooperating in the so-called Club de Berne (CdB) regularly meet in the Counter-Terrorism Group (CTG). Focusing on Islamic extremist terrorism, CTG facilitates operational liaison and provides general threat assessments. Representatives of CTG on a semi-permanent basis, hosted by the Dutch domestic General Intelligence and Security Service (GISS, AIVD in Dutch), assess the jihadist threat using a joint database. See: GLOBSEC, GLOBSEC Intelligence Reform Initiative, p. 16.

23 “Prague Summit Declaration Issued by the Heads of State and Government of the North Atlantic Council in Prague on 21 November 2002.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2002/p02-127e.htm on 13 May 2017; “Istanbul Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government of the North Atlantic Council, Press Release (2004)096, 28 June 2004.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2004/p04-096e.htm on 13 May 2017; John R. Deni, “Beyond Information Sharing: NATO and the Foreign Fighter Threat,” Parameters, Vol. 45, No. 2, Summer 2015, pp. 55-57.

24 Claudia Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism. Where Do We Stand?” NATO Defense College Research Paper, No. 66, April 2011, p. 5; Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” pp. 559-560.

25 Glen M. Segell, “Intelligence Agency Relations Between the European Union and the U.S.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2004, p. 87.

26 Duke, “Intelligence, security and information flows in CFSP,” pp. 616-624; Den Boer, “Counter-Terrorism, Security and Intelligence in the EU,” pp. 403-410.

27 John Nomikos, “A European Intelligence Service for Confronting Terrorism,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2005, pp.

191-203. As cited in: Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, “Rise, Fall and Regeneration: From CIA to EU,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2009, pp. 115-116.

28 Maia De La Baume and Giulia Paravicini, “Europe’s Intelligence ‘Black Hole’. Paris attacks spur calls for a European FBI, but many remain reluctant to share intelligence,” POLITICO, 3 December 2015. Accessed at http://www.politico.eu/article/europes-intelligence-black-hole-europol-fbi-cia-paris-counter-terrorism/ on 14 May 2017.

29 John Kriendler, NATO Intelligence and Early Warning, Conflict Studies Research Center, Special Series 06/13, Swindon, Conflict Studies Research Center, 2006, p. 3; Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, p. 41; Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism,” p. 5; Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” pp. 558-559.

30 Daniel G. Pronk, “Sharing the Burden, Sharing the Secrets. The Fulcrum of Transatlantic Intelligence Cooperation,” draft for Conference “Creating and Challenging the Transatlantic Intelligence Community” presented at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 30 March-1 April 2017, p. 2.

31 Jennifer E. Sims, “Foreign Intelligence Liaison: Devils, Deals, and Details,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2006, p. 202.

32 Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” p. 560.

33 Wesley R. Curtis, A “special relationship”: Bridging the NATO intelligence gap, Monterey, Naval Postgraduate School, June 2013, p. 8.

34 “Istanbul Summit Communiqué,” 28 June 2004.

35 Email correspondence with a senior NATO staff member, 17 May 2017.

36 “Civilian Intelligence Committee (CIC).” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_69278.htm on 15 May 2017.

37 “Todd J. Brown. Director NATO Office of Security.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/who_is_who_112175.htm on 14 May 2017.

38 “International Military Staff.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_64557.htm on 14 May 2017.

39 TTIU was in 2011 absorbed by IS’ IU.

40 Reveron, “Old Allies, New Friends,” p. 461; Kriendler, NATO Intelligence and Early Warning, p. 2; Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, p. 31; Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism,” p. 3; Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” p. 569.

41 Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism,” p. 3; Brian R. Foster, Enhancing the Efficiency of NATO Intelligence Under an ASG-I, Carlisle, United States Army War College, 2013, p.5.

42 At a more conceptual level, (open source) intelligence is shared at Allied Command Transformation (ACT) Norfolk, USA, and its subordinate units like NATO Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre (JALLC) Lisbon, Portugal. Finally, intelligence information is shared at ACT coordinated NATO Centres of Excellence on Human Intelligence (Romania), Defense Against Terrorism (Turkey) and Cooperative Cyber Defence (Estonia).

43 Allied Joint Force Command in Naples, Italy (JFCNP), and Allied Joint Force Command in Brunssum, The Netherlands (JFCBS), are operational level HQs that on behalf of SACEUR conduct the daily operational business in areas of deployment of NATO troops. JFCBS is SHAPE’s intermediate command level for NATO Multi National Corps North East (MNC-NE) in Szczecin, Poland, and JFCNP for Multi National Division South East (MND-SE) in Bucharest, Romania.

44 “DCOS Operations and Intelligence.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.shape.nato.int/page28353414 on 14 May 2017.

45 Foster, Enhancing the Efficiency of NATO Intelligence, pp. 6-7; Email correspondence with a senior NATO staff member, 20 June 2017.

46 Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, p. 38.

47 For the weaknesses of NATO intelligence concerning the Balkans see: Cees Wiebes, Intelligence and the War in Bosnia: 1992-1995, Berlin, LIT Verlag, 2003; Curtis, A “special relationship,” pp. 20-31.

48 For NIFC see: Laurence M. Mixon, Requirements and Challenges Facing the NATO Intelligence Fusion Center, Montgomery, United States Air Force Air War College, 2007.

49 Curtis, A “special relationship,” p. 33.

50 “NIFC.” NATO. Accessed at http://web.ifc.bices.org/about.htm on 14 May 2017.

51 “Warsaw Summit Communiqué,” 9 July 2016.

52 “Exercise boosts NATO intelligence-sharing ahead of Summit.” NATO. Accessed at http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_132882.htm on 14 May 2017.

53 Major General Michael T. Flynn, Capt Matt Pottinger and Paul D. Batchelor, Fixing Intel: A Blueprint for Making Intelligence Relevant in Afghanistan, Washington, DC, Center for a New American Security, January 2010, pp. 7-8; Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, pp. 46-48; Per Norheim-Martinsen and Jacob Aasland Ravndal, “Towards Intelligence-Driven Peace Operations? The Evolution of UN and EU Intelligence Structures,” International Peacekeeping, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2011, p. 456; Curtis, A “special relationship,” p. 32; Stewart Webb, “Improvement Required for Operational and Tactical Intelligence Sharing in NATO,” Defense Against Terrorism Review, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring&Fall 2014, p. 52.

54 Flynn, Fixing Intel, p. 24.

55 Svendsen, “Developing International Intelligence Liaison,” pp. 268-269.

56 GLOBSEC, GLOBSEC Intelligence Reform Initiative, p. 14.

57 Adam D.M. Svendsen, “NATO, Libya Operations and Intelligence Co-operation - a Step Forward?” Baltic Security and Defence Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2011, p. 55.

58 Webb, “Improvement Required,” p. 60; Meeting with a senior NATO staff member, Brussels, 2 May 2017.

59 Meeting with a senior NATO staff member, Brussels, 2 May 2017.

60 Meeting with a senior NATO staff member, Brussels, 3 May 2017.

61 Foster, Enhancing the Efficiency of NATO Intelligence, pp. 1-10.

62 Ibidem, p. 9.

63 Kriendler, NATO Intelligence and Early Warning, pp. 3-4; Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, pp. 14-15; Deni, “Beyond Information Sharing,” pp. 55-56; Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism,” p. 7.

64 Meeting with ASG-ESC, Amb Sorin Ducaru (ROU), Rome, 7 April 2017.

65 Ibidem.

66 Meeting with a senior NATO staff member, Brussels, 3 May 2017.

67 Meeting with a senior NATO staff member, Brussels, 2 May 2017.

68 Meeting with Col Andreas Durst (DEU), G5 Security & Defence Policy, German Ministry of Defence, Berlin, 22 March 2017.

69 Email correspondence with a senior NATO staff member, 17 May 2017.

70 Sims, “Foreign Intelligence Liaison,” p. 202.

71 Mahoney Kennan et al., NATO Intelligence Sharing in the 21st Century. Capstone Research Project, New York, Columbia School of International and Public Affairs, 2013, p. 3.

72 Briefing by Mr Etienne de Gonneville (FRA), French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Paris, 27 March 2017.

73 Sims, “Foreign Intelligence Liaison,” p. 209; Bernasconi, “NATO’s Fight Against Terrorism,” p. 7; Deni, “Beyond Information Sharing,” p. 60; Svendsen, “Developing International Intelligence Liaison,” p. 267.

74 Korkisch, NATO Gets Better Intelligence, p. 42; Florin Negulescu, “Intelligence Sharing and Dissemination in Combined Joint Special Operations,” Journal of Defense Resources Management, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2011, p. 103.

75 Foster, Enhancing the Efficiency of NATO Intelligence, p. 10 and pp. 14-15. The Dutch foreign Defence Intelligence and Security Service (DISS, MIVD in Dutch) is a strong advocate of the use of BICES, see: Netherlands Defence Intelligence and Security Service, 2015 Annual Report, The Hague, Defence Media Centre, 2016, p. 45.

76 “Nations Share Information On Afghan Mission Network,” Defense Daily International, Vol. 12, No. 33, 27 August 2010, p. 5; Webb, “Improvement Required,” pp. 52-53.

77 Wiebes, “De problemen rond de internationale intelligence liaison,” p. 72. As summarized in: Den Boer, “Counter-Terrorism, Security and Intelligence in the EU,” p. 417.

78 “Results in Brief: Improvements Needed in Sharing Tactical Intelligence with the International Security Assistance Force - Afghanistan, Report No. 11-INTEL-13, 18 July 2011.” Office of Inspector General. United States Department of Defense. Accessed at http://www.dodig.mil/Ir/reports/ISAFRIB002.pdf on 14 May 2017.

79 Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” p. 565.

80 Foster, Enhancing the Efficiency of NATO Intelligence, p. 7; Den Boer, “Counter-Terrorism, Security and Intelligence in the EU,” pp. 413-419.

81 Clough, “Quid Pro Quo,” p. 612.

82 Supporting innovative formats of intelligence cooperation is in line with the Polish aim to share assessments on NATO’s Eastern Flank. Briefing by Col Czeslaw Juzwik (ret., POL), Deputy Director of the Armed Forces Supervision Department in the National Security Bureau, Warsaw, 13 June 2017. On legal issues, not being an impediment to such cooperation, see: Commander Shelby L. Hladon, “Is there an Appetite for Information Sharing in NATO?” Transformer, 20 January 2013.

83 “Ex-BND-Vize,” n-tv, 24 October 2016.

84 “NATO leaders agree to do more,” 25 May 2017.

85 Seagle, “Intelligence Sharing Practices,” p. 566

86 For open source see: Nicander, “Understanding Intelligence Community Innovation,” pp. 546-551. Social media in: Marcos Degaut, “Spies and Policymakers: Intelligence in the Information Age,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 31, No. 4, 2016, pp. 516-517.

87 As cited in: Flynn, Fixing Intel, p. 23.

88 Webb, “Improvement Required,” p. 54. Other successful examples of mission fusion are National Intelligence Support Teams (NIST) and Joint Intelligence Operations Centers (JOIC), see: Sims, “Intelligence to counter terror,” p. 54.

89 Briefing by Mr Francesco Sarti (ITA), Scientific Coordinator of Education and Training Activities, European Space Research Institute (ESRIN), Frascati, 19 May 2017; Briefing by Brig Gen Pascal Legai (ret., FRA), Director European Union Satellite Center, ESRIN, Frascati, 19 May 2017.

90 Meeting with Col Thomas Beer (ret., DEU), Copernicus Policy Coordinator, Directorate of Earth Observation Programmes, ESRIN, Frascati, 19 May 2017.

91 Webb, “Improvement Required,” p. 49.

92 Ibidem, p. 58-59.

93 Nicander, “Understanding Intelligence Community Innovation,” p. 542.

94 Björn Fägersten, “Forward Resilience in the Age of Hybrid Threats: The Role of European Intelligence,” in Forward Resilience. Protecting Society in an Interconnected World, Daniel S. Hamilton, ed., Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2014, pp. 124-125. Quote in: Björn Fägersten, “Intelligence and decision-making within the Common Foreign and Security Policy,” Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, Vol. 22, October 2015, p. 11.

95 Based on the list by Teitelbaun (2004). As cited in: Degaut, “Spies and Policymakers,” pp. 524-525.

96 Aldrich, “Transatlantic Intelligence and Security Cooperation,” p. 737.

About the Author

Jan Ballast is a senior staff member, involved with foreign intelligence, mission support and national security, for the Ministry of Defence of The Netherlands.

Thumbnail external page Image courtesy of Nicolas Raymond/Flickr. (CC BY 2.0).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.