Security: What Is It? What Does It Do?

26 Dec 2016

By Marc von Boemcken and Conrad Schetter for Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageFriedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES)call_made in March 2016.

Summary

- The Monopoly on the use of force is a concept that is strongly interlinked with the idea of a state providing security. Therefore it is crucial to consider the different meanings and implications of »security« when reflection on the future of the monopoly on the use of force.

- We suggest that two broad avenues for thinking about security may be distinguished from each other. The first perspective displays a preference for the question what security is. By contrast, the second perspective emphasizes what security does.

- »What is security?«: Many critiques of traditional security studies do not contest the ontology of security itself, but instead denote variations of an »essentialist« understanding of the security paradigm.

- »What does security do?«: Security can also be understood as an inter-subjective social practice. The securitization literature argues that security is what people say. It is a self-referential practice that does not refer to something »more real« and attains visibility only in deliberate social conduct.

In a world of perceived uncertainty and danger, the desire for security becomes a central concern of political thought and action. Against the threatening forces of unpredictability, rapid transformation and complexity, it appears to channel a diffuse longing for greater reliability, stability and tangibility. Ironically, however, the term »security« does not itself possess any stable or consensual meaning. Rather, it marks the perimeters of a highly contested terrain. For how is security to be achieved? Who is to be secured, against which dangers? And, moreover: what actually happens when we »speak security«? To reflect upon any in/security problematic would require us to, first of all, locate our own position and argument vis-à-vis a careful consideration of some basic questions pertaining to the concept and nature of security itself.

For this purpose, we suggest that two broad avenues for thinking about security may be distinguished. The first perspective displays a preference for the question as to what security is (»What is security?«). By contrast, the second perspective emphasizes what security does (»What does security do?«). In the following, both questions will be addressed, arguing that they differ considerably in terms of their ontological, epistemological and normative assumptions. It is, however, not the purpose of this paper to identify the »best« way security can or should be encountered as an object of analysis. Its modest objective is, quite simply, to encourage explicit reflection of the term in question, thereby hopefully diminishing the chances of it being applied in an ambiguous or somewhat vague manner.

What IS Security?

If one sets out to think about security, an obvious starting point might be to ask: what is security anyway? Posing such a question is anything but a trivial exercise, for it already makes an implicit assumption about the very nature of security itself: namely, that such a thing as »security« actually exists. Security, in other words, would refer to an actual condition of existence that is independent of its enunciation in day-to-day discourse. This ontological condition of security has been imagined in quite different ways. For example, in the great debate between Realism and Idealism in International Relations theory it was either thought of as a relative condition in the present or as an absolute condition of the future. In both cases, however, references to security sought to signify certain objectivity. This way of thinking has had at least two implications for the way we ought to go about studying it. First, security is conceived as something that can be objectively known and thus needs to be diligently measured, monitored and improved upon by means of reason and scientific inquiry. Second, security attains a normative quality: it appears as a »good thing« we ought to actively aspire to.

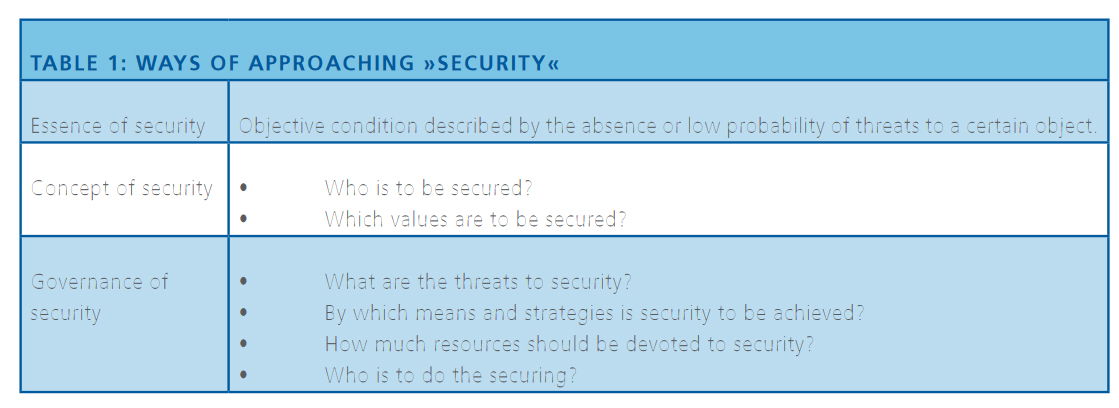

From such a perspective, the general definition of security is usually thought to be encountered in the absence – or at least unlikeliness – of threats to a certain object. For example, David Baldwin has defined security astutely as »a low probability of damage to acquired values« (1997, 13). Similarly, for Lawrence Krause and Joseph Nye it was »… the absence of acute threats to the minimal acceptable levels of the basic values that a people consider essential to its survival« (1975, 330). Such definitions of security seek to somehow capture the underlying essence of the term. However, it may yet be conceptualized in quite different ways. In order to move from the essence to the concept of security in the context of a particular academic and/ or political project, the most important question to be addressed is: security for whom? In most cases, the answer would either refer to some or all individuals or to some or all states. It needs to be remembered, however, that security may be equally applied to such diverse objects as, for example, animal life, the biosphere or physical infrastructure.

To further specify the object of security, it may be necessary not simply to point to the actual entity in need of security, but to also identify the endangered values that this particular entity contains or represents. For instance, a human being can be associated with several values, all of which may be worth securing. In such a case, a concept of security needs to be clear on whether it refers to corporeal integrity, economic welfare, autonomy or psychological well-being. In the end, different objects and values yield rather different conceptualizations of security, the most prominent of which are of course »human life« and »state sovereignty«.

Taken by itself, the idea of »environmental security« is therefore not an accurately specified security concept, for it remains very much open who or what is to be secured. Are we talking about the territorial integrity of a South Pacific island state threatened by climate change and rising sea levels? Or do we seek to address the decline of individual human well-being and prosperity due to desertification processes? Maybe our object of security is neither the state nor the individual but the environment itself. But which part of the environment? A certain endangered species or the entire biosphere? Naturally, many of the different security concepts gathered under the umbrella of »environmental security« are closely related. However, they may also oppose, even conflict with each other. This is aptly illustrated by the brown bear that rampaged through the forests of Bavaria in the summer of 2007. Identified as a problem (»Problembär«), for threatening livestock, the bear was eventually killed. This security measure clearly overrode an alternative conceptualization of security that would have taken the physical integrity of the animal itself as its principal object. To the extent that different concepts of security may contradict each other, it is thus of utmost importance that we specify whose security we are actually talking about when partaking in a discussion on security issues.

Once the essence and the concept of security have been clearly delineated, it is, in a third step, possible to think about the pursuit of security. Here, Baldwin (1997) has suggested a couple of additional relevant questions. First and depending upon the particular object of concern, the actual threats to security need to be identified. Second we have to ask ourselves which means and strategies ought to be employed in order to minimise, or even eradicate these threats. Do we revert to coercive military means favouring strategies of surviving and/or deterring danger; or do we prefer civil, for example developmental, means directed against the root causes of threats and thereby associated with strategies of overcoming and transcending danger? Third, we ought to consider how much resources should be devoted to increasing security, and how the resources spent should be divided among different means and strategies. Finally, Emma Rothschild (1995: 55) has put forward a further important question, namely: Who is going to do the securing? Is it always state institutions that are best suited to provide security, or is there also a role for the private and/or non-governmental sector to play?

If we decide to perceive security, including »environmental security«, as both a normative policy goal and a knowable and objective condition of existence, then the procedure outlined above might well serve as a useful guide to clearly specify our object of analysis, distinguish it from alternative conceptualizations of security, and conduct research in a coherent and policy-relevant manner. Indeed, we would suggest that the largest part of the debate concerned with the »redefinition« of security following the end of the Cold War can be traced along the lines of different approaches (see Table 1) to answer the above questions. Many critiques of traditional security studies therefore do not contest the ontology of security itself, but instead denote tactical variations within the overriding model of what might be thought of as an »essentialist« security paradigm.

What Does Security Do?

Although the by far most popular and mainstream approach to the study of security, the »essentialist« perspective is by no means the only way to analytically engage security issues. Instead of asking »what is security?« a very different and perhaps a more interesting question is: »what does security do?« To pose such a question represents a great deal more than to simply adopting a slightly different research angle. For in departing from the essentialist assumptions of security as an objective, knowable and good thing, it implies a profound departure in ontological, epistemological and normative terms. Security and insecurity would thus not be considered as aggregate conditions of existence that are objectively »out there« and present themselves to us as unquestionable facts of life. Instead, they are thought of as socially constructed by certain actors and for particular purposes. As Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap de Wilde (1998: 31) have noted in their influential book Security – A New Framework for Analysis, security needs to be understood as an inter-subjective social practice, as something we do. It is, in other words, »… a specific social category that arises out of, and is constituted in, political practice« (ibid.: 40).

Such a »constructivist« perspective implies a certain way of approaching and studying security. It would not begin with a laborious effort to identify and define the underlying, essential meaning of security, but restrict its analytical scope to the discursive and practical manifestation of the term in social and political life. Security is, quite simply, no more (or less) than what people say it is. It is a self-referential practice that does not refer to something »more real« and attains visibility only in deliberate social conduct. Or in the words of Wæver: »It is by labelling something a security issue that it becomes one – not that issues are security issues in themselves and then afterwards possibly talked about in terms of security« (Wæver 2000: 8; emphasis added). Notwithstanding the questions outlined in the previous section, we would therefore have to ask, more fundamentally: What happens when certain issues are treated as security issues?

The most well-known response to this question is the so-called »securitization« theory developed by Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde (1998). By securitization the authors mean a succession of authoritative claims or statements wherein a particular issue (be it military, political, economic, societal or environmental) is successfully presented as an existential threat to a referent object, in turn requiring emergency measures exceeding »… the normal bounds of political procedure« by legitimizing the breaking of established norms and rules (ibid.: 23–4, 25). As they go on to argue, securitization is but one, albeit the most extreme, form of rendering an issue a problem of governance. In this sense, it may be differentiated from »politicization« as the process by which a problem enters an open public debate, becomes part of a political bargaining process and eventually may (or may not) receive certain resource allocations (ibid.: 23). By contrast, if an issue is securitized it is presented as so urgent, existential and important »… that it should not be exposed to the normal haggling of politics« (ibid.: 29). It is lifted beyond politics and – by implication – beyond the mechanisms of democratic control and oversight.

Securitization theory is a good example of the analytic shift from »what security is« to »what security does«. Importantly, it highlights the profound change in the normative orientation of analysis. Since threats are not self-evident but always subject to practices of political representation, whether certain issues should be framed and treated as security issues (whether they should be securitized) is a conscious and deliberate decision. For Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde this decision should not be taken lightly. Indeed, they argue that it is usually better to opt for »de-securitization«, that is: to switch out of emergency mode and back into the open deliberations of »normal« politics.

Obviously, the word »security« may well be uttered in political discourse without necessarily securitizing a particular issue in the sense outlined above. Especially on the domestic level, in the day-to-day proceedings of internal security governance, security may not securitize as much as it may order social relations in many other ways. Whereas these more mundane »doings« of security remain largely unexplored, securitization theory represents a useful, though limited, tool for analysing the function of security in the international and global realm. A case in point is, of course, the US-led »War on Terror«, securitizing the issue of terrorism to the extent that it justifies measures that violate human rights and international law. However, securitization strategies may also be encountered in far less obvious places, employed in relation to threats other than military ones and adopted by actors other than states. For example, it could be argued that Greenpeace goes some way towards securitizing environmental issues as existential threats, thereby legitimizing actions outside the normal bounds of political behaviour and in many cases even conflicting with the law.

More generally, when thinking about the relation between the environment and security, it is important to keep in mind the question »what security does«. Here, the strong military connotation which the term »security« encompasses in political discourse is of relevance for analysis. In consequence, treating environmental problems as security problems could lead either to a possible militarization of environmental policy or, vice versa, to a demilitarization of the term security itself (cf. Brock 1992). The discursive effect of conflating environmental and security issues would need to be empirically established from case to case. Finally, it is worth noting that to present an issue as a security problem always serves the purpose of instilling that issue with a particular sense of urgency. For this reason, it might well be the case that the discourse of »environmental security« can be understood, fi and foremost, as a deliberate strategy on the part of certain actors to advance environmental issues up the political agenda.

Conclusion

This paper has suggested two very different ways to approach, to think about and to analyse security. One approach is not necessarily »better« than the other and the choice depends very much on the specific research question that one sets out to answer. In any case, we hope to have demonstrated that – regardless of the perspective one eventually adopts – there is a clear need to begin a security analysis with some reflection on the meaning and approaching of security itself. Such reflection will either serve the purpose of specifying the concept of security that one intends to deploy when assessing an objective security condition; alternatively, it may also, however, sensitize analysis toward the inter-subjective function of security in political discourse.

References

Baldwin, David A. 1997. The Concept of Security. Review of International Studies 23: 5–26.

Brock, Lothar. 1992. Peace through Parks: The Environment on the Peace Research Agenda. Journal of Peace Research 28 (4): 407–23.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, CO / London: Lynne Rienner.

Krause, Lawrence, and Joseph Nye. 1975. Reflections on the Economics and Politics of International Economic Organisations. In: Bergsten and Krause (eds.) World Politics and International Economics. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institute.

Rothschild, Emma. 1995. What is Security? Daedalus 124 (3): 53–98.

Wæver, Ole. 2000. Security Agendas Old and New, and How to Survive Them, Working Paper 6. Buenos Aires: Universidad Torcuato Di Tella.

About the Authors

Marc von Boemcken is a Senior Researcher and Project Leader at the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC), teaches security policy and peace and conflict research at the Bonn University and is the co-editor of the annual German Peace Report (Friedensgutachen).

Conrad Schetter is director for research at the Bonn International Center for Conversion, a Professor for Peace and Conflict Studies at Bonn University and Associated Member of the Center for Development Research (ZEF) Directorate.

The views expressed in this Think Piece are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung or the institution to which he/she is affiliated.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.