The Transformation of European Armaments Policies

13 Nov 2018

By Michael Haas and Annabelle Vuille for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in November 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Despite moderate growth in European defense budgets, conditions remain unfavorable for closing the investment gap that has emerged in the area of military equipment since the 1990s. In a majority of European states, defense and armaments planners are still confronted with a modernization backlog that will be difficult to eliminate with budgeted funds.

Disproportional cost increases and inefficient procurement processes, which are seen as causative elements of the structural crisis in arms procurement by some, are important aggravating factors in this regard. However, if we adopt a longer-term perspective, it becomes clear that the current urgent need for modernization is chiefly due to a set of flawed assumptions about the future development of European security that have largely proven unsustainable. At the same time, the effects of advancing material fatigue are making themselves felt with increasingly force. After the end of the Cold War confrontation, given the perception that the plausibility of conventional conflict scenarios had diminished, it seemed justified to put major armaments investments on the back burner. Political deferments, structural adaptations of the armed forces, and upgrading of comparatively “young” main weapon systems allowed the planners to temporarily preserve the basic elements of a military defense capability.

From a broader, societal point of view, this approach has indeed proven beneficial over the past two decades, and has facilitated the reallocation of funds to other priorities. However, considering that many current systems are reaching the end of their useful service life, this approach has now largely exhausted itself. At the same time, the security policy environment has shifted markedly. Against this background, even governments outside the NATO sphere acknowledge openly that the expectation that military risks will remain negligible cannot necessarily be extended into the 2030s and beyond. Therefore, the need to formulate forward-looking political foundations for arms procurement is once again gaining importance. In line with the expectations presented in CSS Analyses No. 181 and 182, the focus of these developments is – once more – at the national level.

Instruments and Options

The main responsibility of national governments in shaping armaments policy is to set the appropriate framework conditions for the procurement and maintenance of military capabilities, both for their own administrative units and for private corporate actors. This involves compliance with extensive legal requirements as well as the observance of important structural restrictions imposed by the national context. In many European states, civil society is increasingly also making its voice heard when it comes to arms procurement. Under conditions of considerable regulation density and an increasing requirement for transparency and legitimacy, procuring complex weapon systems on time with moderate budgetary means has become an almost insurmountable challenge.

Certain traditional political levers in armaments policy – such as the setting of political guidelines for procurement and international cooperation, the shaping of industrial policy, the regulation of industrial participation and offset agreements, or the application of adequate transparency measures – remain effective tools. However, there are also practical risks associated with the implementation of highly complex technology projects, including the possibility of delays and cost increases over the course of the project. Due to the very nature of such projects, it is difficult to eliminate these risks outright by political means. This is obviously the case when, as in most European states, there are strong dependencies on international suppliers who, while being subject to regulatory measures imposed by the purchasing state, are not subject to its immediate political influence. Neither is there good evidence to show that direct intervention by political actors in arms development and procurement processes has a positive impact on outcomes, even where such interventions are still part of the arms procurement toolbox.

Thus, any attempt at identifying areas in which armaments policies can have a beneficial influence must result in a differentiated assessment. Neither its internal functions nor its international relevance should be underestimated. In the domestic context, a normative framework that combines a sober focus on national interests with an adequate consideration of changing societal conditions can undoubtedly be conducive to fostering legitimacy. In interactions with potential foreign cooperation partners, too, clear political guidelines can build confidence and contribute to an alignment of expectations at an early stage. At the same time, however, arms policy must take into account a number of factors on which it has only limited influence.

Constant Decline of Purchasing Power

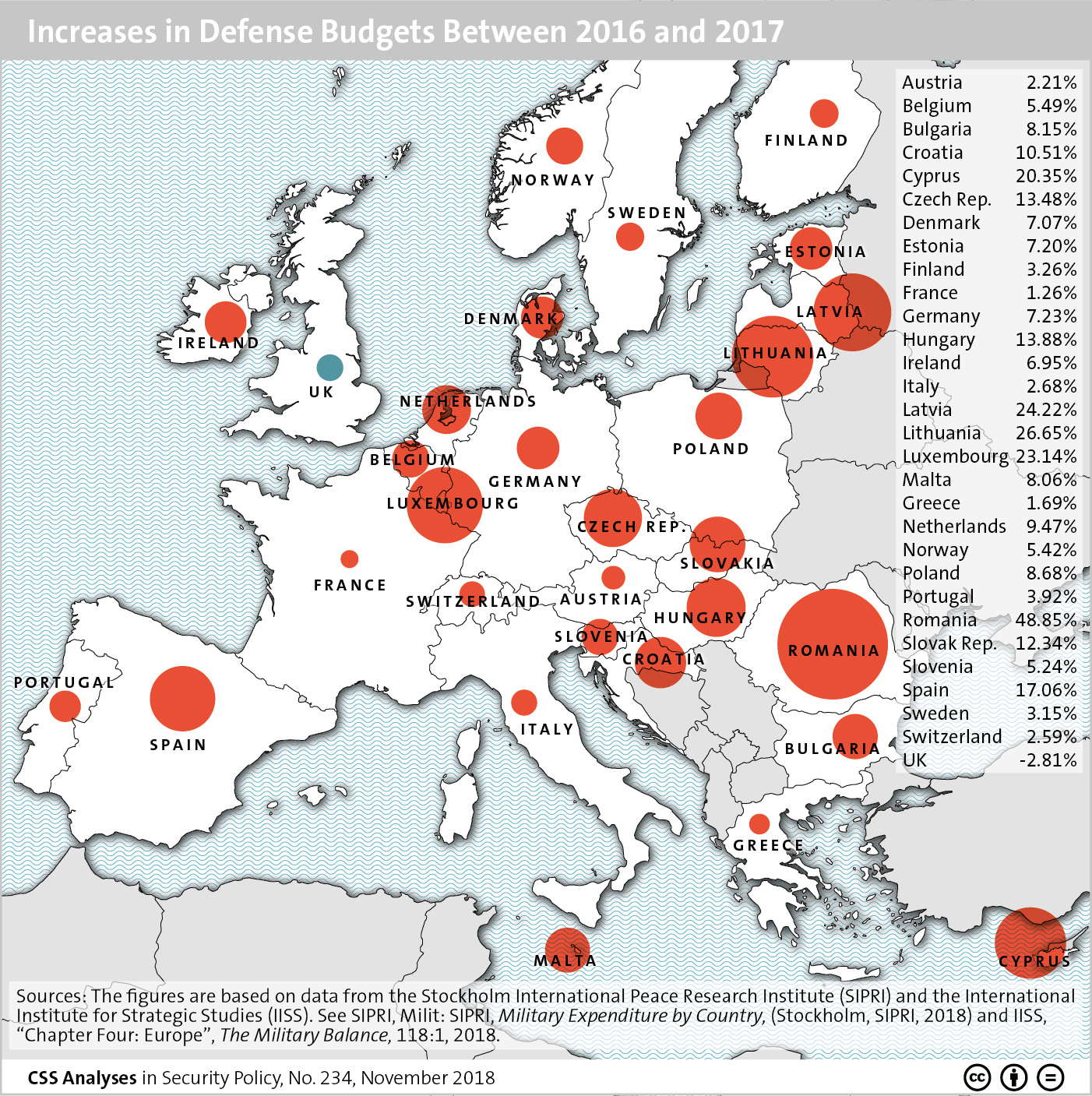

In 2017, European defense budgets once more increased at an average rate of 4.25 per cent. At the same time, many European states are confronted with the curse of disproportional cost increases in the development and procurement of armaments – a challenge sometimes described as the “defense economic problem”. This is resulting in more and more painful conflicts over resource allocation within the armed forces. Studies have shown that the price tags of complex air, land, and naval military systems increase significantly faster on a yearto-year basis than those of civilian goods. For instance, an annual cost increase of 7 to 12 per cent has been observed in US-built military aircraft. The bulk of this increase was due to the growing complexity of the systems involved, while the total share of the annual increase that was due to manufacturers’ profit margins and other economic factors was roughly in line with civilian price indexes. Comparable statistics relating to other technologically complex systems can also be found for other important arms-supplying nations. When measured against civilian inflation rates, therefore, real budget increases of several per cent may not lead to a corresponding increase of purchasing power for procurement agencies – they are only slowing down the steady erosion of the agencies’ financial maneuvering room. At the same time, price hikes are mainly due to customer requests. With regard to economic efficiency, the leeway for optimization on the industry side is relatively limited. Where economies of scale that could bring down prices for major procurement projects are lacking, and where political decisionmakers prefer to limit open competition across national borders that could end the quasi-monopolistic status of individual suppliers, it appears rather unlikely that cost escalation can be successfully contained.

The increase of personnel costs that coincides with the growing need for investment in materiel is further aggravating the basic defense economic problem. To some extent, Switzerland is an outlier in this context. The Swiss Army’s financial planning, with a target investment quota of 40 per cent by 2020, is rather ambitious in comparison with the rest of Europe. This is possible partly due to the Swiss militia system, with its comparatively low share of personnel costs. That said, a high level of investment may also result in problems that are difficult to avoid when rapidly implementing advanced technology projects.

Meanwhile, there is no guarantee of constant mid- to long-term budget growth even at the level seen in past years. Since defense expenditures have often developed in an anticyclical fashion in the past, it is not necessarily the case that lower economic growth will automatically bring deep budget cuts. However, in most European states, repeated high single-digit or even double-digit increases that could bring an effective expansion of investment-related leeway seem out of the question for now. Armaments policy must adapt to the present environment. The highly constricted budgetary realities therefore create a dilemma for European nation states: On the one hand, weapon systems should match users’ specific requirements as comprehensively as possible. On the other, reasonable savings can mainly be achieved by reducing complexity or through a notable increase of produced units as a result of coordinated, cooperative procurement.

Forced to Cooperate

Given the creeping erosion of the realworld scope for investments, military planners in many capitals are barely able any more to reconcile the already reduced requirements mandated by defense and armaments policy with the available means. At the same time, market developments and political decisions have in places weakened national defense industries without leading to the emergence of an integrated European armaments industry. Therefore, bilateral or minilateral international arms cooperation agreements are indispensable for small states and middle powers – both in terms of creating reasonable frameworks for individual procurement programs and for securing advantages in the medium to long term. In fact, even for established powers with significant arms industries, attempts at self-sufficiency in research, development, and production are proving increasingly problematic.

It is worth noting that cooperative efforts continue to be the stated aim, serving both as pragmatic options at the nation-state level and as political projects for enhancing relations between states. In practice, both motivations frequently play a role. Cooperation projects continue to be regarded as instruments for optimizing costs and efficiency – especially in the case of capitalintensive and technologically challenging projects such as fighter aircraft. Here, cooperation with partner states in Europe can yield considerable benefits. Certainly, it is much more likely that economies of scale can be achieved and that the variable costs per unit can be reduced in such a framework. That said, these desirable advantages are not fully realized in most cases. At the same time, cooperation agreements may also be useful for shielding controversial programs from domestic political or occasionally even legal difficulties. Sometimes, they offer access to additional financing, for instance by using external sources of funding such as the newly instituted European Defence Fund to cover high research and development (R&D) costs or by splitting these costs equally or proportionately among participating states.

The latter scenario offers the additional advantage of helping to secure the competitiveness and survival of national armaments industries through the ability to participate in R&D and production activities. The latest collection of data by the European Defence Agency shows that today, about one quarter of the relevant expenditures end up in joint programs, with a clear trend towards bilateral and multilateral contracts involving European partners. Since 2009, between 85 and 95 per cent of the agency’s total expenditures have been invested as part of cooperative procurement of military assets with the participation of at least two member states.

The European Commission, too, aims to raise the degree of coordination and cooperation in European defense procurement through several measures included in the 2016 European Defence Action Plan. At the core of this strategy is the European Defence Fund. It envisages the disbursement of about 90 million Euros per year for multinational R&D activities until 2019. Until 2020, about 500 million Euros annually are to be spent on development and procurement to support the joint development of capabilities by project consortia involving three companies from two or more member states. This far-reaching initiative aims at bringing about cooperation models through financial incentives rather than further regulatory measures or tightening of procurement directives.

The aim of these longstanding aspirations for integration and consolidation of the European defense market is to increase interoperability as a way of enhancing the EU’s security, as well as to reduce the considerable remaining inefficiencies and functional duplications. For instance, the EU member states continue to afford the luxury of maintaining about 17 different types of main battle tanks, 29 types of surface vessels, and 22 types of combat aircraft. Moreover, by minimizing this persistent fragmentation, opportunity costs of at least 30 billion Euros annually – the so called “costs of non-Europe” – are to be avoided in the future. It is currently still unclear how this incentive structure will directly affect the willingness of EU member states to cooperate and whether this will lead to an effective reduction of protectionism in the armaments sector in the long run.

The Contribution of Industrial Policy

In fact, despite some progress, multinational arms cooperation remains the exception: On average, more than 80 per cent of member states’ investments continue to be funneled into projects at the national level. While the funds involved here do not benefit national suppliers exclusively, this is still evident that the willingness to engage in joint procurement outside of national vehicles remains limited. An investigation by the European Parliament into public contracts awarded between 2011 and 2014 showed that in the case of the larger states – Germany, France, the UK, and Italy – the share of domestic suppliers remained nearly unchanged at between 92 and 98 per cent.

Whether these states gain any crucial advantages by adhering to traditional selfserving industrial policies must be determined on a case-by-case basis. From a broader perspective, the armaments policies of the larger states reveal tendencies towards inertia, combined with a merely situational enthusiasm for European solutions. To some observers, this even suggests a return to the nationalist armaments policies of decades past. While this perception may be exaggerated, the potential for further integration appears limited, even if the hesitant trend towards more openness can be expected to continue.

A different approach is adopted by those smaller states that focus on fostering efficient industrial niche capabilities and bring their industrial capabilities to the negotiating table as a bargaining chip in the search for sustainable international cooperation models. While many of these policies are also ostensibly designed to preserve existing structures, there is a good case to be made that the existence of a competitive industrial base has positive effects on the framework conditions for such cooperation schemes. Thus, especially for smaller states, a streamlined but productive industrial base constitutes a significant asset for armaments policies that are adapted to the international setting as well as internally consistent.

Swiss Armament Policy

The principles of Swiss arms procurement policy are defined by the Federal Council and substantiated by the the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sports in subordinate documents. Since the end of October 2018, a external pagerevised versioncall_made of the “Principles of the Swiss Federal Council for the Armament Policy of the DDPS” has been available. The detailed presentation of arms policy requirements in publicly accessible documents demonstrates a comparatively high degree of transparency and is quite remarkable by international standards. In the context of the revision of Swiss arms policy, the CSS has also looked at policy trends in selected European states and published the results of this work in a CSS study.

Realignment of the Non-Allied States

Just as a balanced armaments policy benefits from a well-adapted industrial element, the procurement of military assets has increasingly proven a useful element of changing security strategies since 2014. This is especially true for those states that seek closer integration with the Euro-Atlantic security system outside of the NATO alliance. For example, Sweden decided in August 2018 to underscore its closer cooperation with the US by purchasing the Patriot air defense system. Officially, the reason for this decision was the advanced state of development and proven performance of the US product compared to the French-Italian SAMP/T system. In fact, Sweden also had to accept significant compromises in a number of areas, including offsets and the overall price tag. These trade-offs make real sense only in the context of Stockholm’s desire to deepen its relationship with Washington in the areas of defense and armaments.

Sweden’s Scandinavian neighbor Finland has adopted a similar view with regard to the potential political opportunities involved in the replacement of its 64 F/A-18 Hornet fighters. Much as in the early 1990s, when the F/A-18 was first purchased, the procurement project is to be leveraged as a way of securing stronger political relations and thus strengthening Finland’s security relationships even without formal membership in the North Atlantic alliance. In this way, it is hoped that new or deepened partnerships in the armaments sector can serve to foster military stability and become an implicit component of Finland’s deterrent capacity.

Although this is only one possible approach towards developing an armaments policy that is well integrated with national security policies, both non-allied countries demonstrate how a rather limited arms policy toolkit can be assertively leveraged to good effect. If they succeed in this regard, it is not only because their ambitions are in line with their respective nations’ requirements, but also because there is sufficient support for major projects both in the political arena and within the population at large. In view of limited budgetary discretion, the key factors here are a long-term active information policy and strenuous efforts to build the broadest possible societal consensus well ahead of time.

Today, a proactive and broad-based armaments policy is once more a crucial building block of security and military policy, especially in view of the evident limitations that affect many European states in comparable ways. Such policies, if adapted to the respective national context and cognizant of the potential for closer political as well as industrial collaboration with suitable and compatible partners, can be a major factor in overcoming the modernization gap in the defense sector.

About the Authors

Michael Haas is a researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS). His work focuses on military technology and policy.

Annabelle Vuille is a CSS researcher. Among other issues, she studies the armaments policies and procurement decisions of small states.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.