No 97, Caucasus Analytical Digest: Religious Institutions and Democratization

7 Aug 2017

By Fuad Aliyev, Salome Minesashvili and Narek Mkrtchyan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Caucasus Analytical Digest on 21 July 2017.

Introduction by the Special Editor

By Kornely Kakachia (Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University)

The relationship between religion and politics continues to be an important theme disputed and interpreted differently amongst politicians and scholars. The same is true for the relationship between democracy and religion. While there is no general consensus about the topic, everyone realizes the importance of the debates between religion and democracy. As former British Prime Minister Tony Blair eloquently noted, “We need religion-friendly democracy and democracy-friendly religion”1.

Many of the theories surrounding this topic focus on the love-hate relationship between religion and democracy. Alfred Stepan (2005) outlines the concept of “twin tolerations” and differentiation, proposing a template that can be applied to all kinds of religion–democracy relationships2. According to him, “twin tolerations” means that there is a clear distinction and mutual respect between political authorities and religious leaders and bodies. A country’s ability to implement the principle of differentiation directly affects its successful development of democracy. Searching the inter-linkages between religion and democracy, Driessen (2010) notes that, “Once the core autonomy prerequisites [of democracy] have been fulfilled, there is a wide range of Church–state arrangements which allow for religion to have a public role in political life and simultaneously maintain a high quality of democratic rights and freedoms”3. Philpott (2007) observes that, even within the “Third Wave” of democratization, religion has played a tremendously important role in promoting democracy in some places (e.g., Poland, Lithuania and Indonesia) though not in others (e.g., Argentina and Senegal)4.

While the topic of religion has been substantially covered by special literature5 on the South Caucasus, religious organizations and their impact on democratic transition and consolidation have been largely left out of these studies. As religious institutions have played a critical role in the political changes in the South Caucasus, some scholars6 have argued that religion has had the effect of challenging democratic values and socialization while also potentially boosting democratic attitudes by fostering trust in institutions and engagement in politics.7

Currently, societies in South Caucasian countries lack both strong political will and the experience necessary for democratic governance. Recent years have also brought new challenges, including democracy fatigue. The process of democratization is not an easy one: the necessary reforms and changes force society to rethink long-held beliefs and traditions and are often the subject of a public debate that powerful groups seek to influence, including religious institutions.

In the case of South Caucasian countries, religious organizations—namely, the Georgian Orthodox Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Caucasus Muslims Department of Azerbaijan—are frequently named as some of the most trusted institutions in their respective countries. These institutions have declared their intent to remain detached from the centre of politics in their respective societies, though they still exert influence in political affairs. Their stance on democracy-related issues has already impacted political decision-making on a number of occasions. Moreover, outside powers are also trying to use religion as a “soft power” tool to maintain their influence in the region8.

In the light of this challenging environment, the contributors to this special issue of the Caucasus Analytical Digest analyse the attitudes, values and behaviour of the aforementioned religious institutions in the context of democratization. Assuming that democracy and religion need not be incompatible and can be valid partners, the contributions look at the relations and interactions of these religious institutions with the state and civil society. They also try to explore answers to the question of whether there is any chance to engage religious institutions in democratization processes and include them in public and political debates.

Notes

1 Tony Blair. Religion-friendly democracy and democracy-friendly religion. The Guardian. November 11, 2011. <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/nov/11/tony-blair-democracy-friendly-religion>

2 Alfred C. Stepan. Religion, Democracy, and the “Twin Tolerations”. Journal of Democracy, Volume 11, Number 4, October 2000, pp. 37–57.

3 Driessen, M., 2010. “Religion, State, and Democracy: Analyzing Two Dimensions of Church–State Arrangements”, Politics and Religion, vol. 3, no. 1 (April 2010): 55–80.

4 Philpott, Daniel, ‘Explaining the Political Ambivalence of Religion’, American Political Science Review, 101 (2007), 505–525

5 See: Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus. (2014) edited by: Alexander Agadjanian, Ansgar Jödicke, Evert van der Zweerde. Routledge

6 Andrea Filetti (2014) Religiosity in the South Caucasus: searching for an underlying logic of religion’s impact on political attitudes. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies Vol. 14, Iss. 2,2014

7 See: Pazit Ben-Nun Bloom and Gizem Arikan (2013) Religion and Support for Democracy: A Cross-National Test of the Mediating Mechanisms.

British Journal of Political science. Get access Volume 43, Issue 2 April 2013, pp. 375–397. <https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/religion-and-support-for-democracy-a-crossnational-test-of-the-mediating-mechanisms/8708F3860AC266FE987F5E4DFEC75172>

8 Religion and Soft Power In South Caucasus Policy Perspective. (2017) Editors: Ansgar Jödicke, Kornely Kakachia. Georgian Institute of Politics. Tbilisi. Available at: <http://gip.ge/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Memo.pdf>

The Role of the Caucasus Muslims Board in the State Building of Post-Soviet Azerbaijan

By Fuad Aliyev (Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy University, Baku)

Abstract

This contribution discusses the role played by the Caucasus Muslims Board, a formal religious institution, during the state building process of post-Soviet Azerbaijan and its potential for supporting democratization in the country. The contribution argues that this institution has served as a regulatory body for Muslim communities and Islamic activism and has been dependent on the state for its operations. It claims that there is little chance to engage the board in the democratization process, though it still should be included in relevant public debates given its potential ability to influence Azerbaijani society and impact the country’s political agenda in the long term.

Introduction

After the collapse of 70 years of official atheism, religion started to revive and play an important role in the societies of post-Soviet republics of the South Caucasus. The only Muslim-majority country in this region, Azerbaijan, has seen the building of new and modernizing of old mosques, an increasing number of Islamic study centers, schools and universities and thousands of pilgrims going to Mecca for Hajj every year.

Religious revival has played an important role in post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Since Islam does not separate the secular life from the spiritual, it implies more active involvement in political events. The concepts of “Islamic” and “national” are closely intertwined in Muslim identities. During the years of Soviet atheism, people continued to follow some Islamic customs and rites, understanding them as national and not religious (Aliyev 2004).

While preaching aggressive atheism, the Soviet Union realized the importance of religion as a tool of social mobilization and popular culture and thus tried to control and utilize religion for its own benefit (Swietechowski 2002). This required the presence of and cooperation with formal religious institutions. Since Islam does not recognize the institution of the church, the Soviet authorities followed the practices of the Russian Empire by recreating various formal institutions and cultivating homegrown religious leaders. Azerbaijan also had an institution known as the Religious (Spiritual) Board, which continued its operations after the collapse of the Soviet Union and became an important contributor to Islamic revival and state-religion relations.

This contribution will focus on the Caucasus Muslims Board (CMB) in Azerbaijan and its role in Islamic revival and state-religious relations in order to explore how it could actually take part in state building. It will also determine if there is any potential for this organization to support the democratization process in the country. The contribution argues that the CMB, while a non-governmental institution, has played the role of a regulatory body for Muslim communities and Islamic activism; as a result, unlike churches in Armenia and Georgia, it did not have any independence. Although Dr. Allahshukur Pashazade, the head of the Board, is an influential person in the political establishment, he does not have any independent stance on democracy-related issues. The contribution concludes that there is little chance to engage this institution in democratization; however, including it in public and political debates could help the institution broaden its perspectives and increase its significance. In the long term, the CMB could potentially become an asset for democratization in Azerbaijan.

The Caucasus Muslims Board: Institutional Background

During Soviet rule and the time of militant atheism, official “independent” Muslim religious administrations continued to operate; these included the Muslim Religious (Spiritual) Board for the European USSR and Siberia (centered in Ufa in the Bashkir ASSR); the Muslim Religious Board for Central Asia and Kazakhstan (Tashkent, Uzbekistan); the Muslim Religious Board for the North Caucasus (in Buinaksk and later in Makhachkala, Daghestan); and the Muslim Religious Board for Transcaucasia (Baku, Azerbaijan). These boards did not oppose Soviet rule and even tried to find similarities between the communist ideology put into practice after the October Revolution and Qur’anic values, such as the equality of nations and sexes, freedom of religion, security of honorable work, ownership of land by those who till it, and more (Saroyan 1997).

During the Soviet era (until Gorbachev’s reforms), the Muslim Religious Board for Central Asia and Kazakhstan, located in Tashkent, was at the head of Islamic affairs. This religious body had more rights and advantages than other boards. It issued the only official Muslim journal, “Muslims of the Soviet East,” and was responsible for other literature and publications about Islam. In fact, a Muslim administrative elite emerged and developed around this board that tried to promote its own authority and undermine any alternatives (Saroyan 1997). The Muslim Religious Board for Transcaucasia, the predecessor to CMB, and its leader since 1980, Sheikh-ul-Islam Allahshukur Pashazade, were also part of this administrative elite.

Perestroika, followed by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, brought fragmentation and regionalization to Soviet clerical elites. In 1990, an assembly of Muslim clerics in Alma-Ata declared the establishment of a Muslim Board for Kazakhstan. Central Asian boards based in Tashkent did not recognize the legitimacy of this new board, but others followed the same fragmentation path, including the institution in Baku, which was officially reborn in 1992 as an Azerbaijani national institution.

While rebranded and reorganized after Azerbaijan attained its independence, the CMB differs little from its Soviet predecessor in terms of concept or structure. It also lost any formal influence and connection to the Sunni-dominated Board of the North Caucasus.

In the meantime, the rapidly changing political environment created conditions for new forms of Muslim religious associations to emerge. In the past, Muslim religious boards could rely in part on the coercive power of Moscow to prevent the emergence of independent Muslim religious centers (Aliyev 2004). Subsequent independence and liberalization allowed new Muslim religious movements and actors to emerge, some of which were supported externally and some of which were even radical (Aliyev 2007). This milestone can be considered the official start of the so-called “Islamic revival” in Azerbaijan.

In contrast to other boards, Transcaucasus Muslim elites have operated under slightly different conditions. Aside from its jurisdiction over Muslims in Armenia (before they were massacred or deported at the beginning of the Azerbaijan–Armenia Nagorno-Karabakh conflict) and Georgia (where in any case most Muslims are ethnic Azerbaijanis), the Baku religious board is staffed by Azerbaijanis and serves an Azerbaijani community (Aliyev 2004). The administration can be characterized as an Azerbaijani national institution.

Overlap between religious and national customs and identities is very common, since “Muslim” is coterminous with “Azerbaijani” (Motika 2001). Another important factor is that the Baku board was also heir to a religious administration established during the Tsarist period (first in Tbilisi), with the Sheikh-ul-Islam serving as the leader of Azerbaijani Shias and his deputy Mufti as the leader for Azerbaijani Sunnis. Thus, there is some historical precedent for Azerbaijanis. Probably even more important, however, is that Azerbaijan’s Muslim community is predominantly Shiite. In contrast to Sunni Islam, formal religious hierarchy is not foreign to the historical development of this branch of Islam. Thus, the existence of official institutions regulating religious life can be seen as part of Azerbaijan’s Shiite heritage (Saroyan 1997).

State–Religion Relations in the Republic of Azerbaijan

Sheikh-ul-Islam Allahshukur Pashazade, the head of the CMB, played a significant role during the pre- and post-independence years. He openly opposed the massacre by Soviet troops in Baku in January 1990 and personally orchestrated the use of the funerals of victims as mass protests against the government’s brutality. It required courage and national patriotism on his part, which the general public appreciated, to stand up to the Soviet government. Dr. Pashazade’s peace-making efforts during the war in Karabakh also furthered the respect and legitimacy of the CMB and associated him with it. In this regard, the CMB’s contribution of popular mobilization and support for independence and nation-building in the initial phase of Azerbaijan’s post-Soviet experience is undeniable. However, as the Islamic revival continued, the prestige and influence of the CMB started to evaporate, while that of some other members of the unofficial Muslim clergy was on the rise (Aliyev 2007). Islam became a rallying point for the dispossessed, impoverished and unemployed and even simply for those Azerbaijanis who rejected many aspects of Western culture (Aliyev 2007). For reasons discussed below, however, the CMB could not respond to these changing and growing popular needs.

As far as the relationship between the government and Islam is concerned, it should be noted that the CMB has never opposed any government in power since independence. It has turned into the unofficial forum for regulating Islamic activism in the country. Although the government adopts some external trappings of Islam and defends it as a part of national identity, it does not welcome any Islam-related activity over which it has no control. The CMB is instrumental to the successful implementation of this paternalistic policy, aiming to ensure that all religious activity is subject to government control. It looks like a pact between the stronger state and the weaker CMB: its clerics support the government, and the government takes care of them.

This contribution’s author worked as an evaluator of the US government-funded Islam in a Democratic Azerbaijan program implemented by the Eurasia Partnership Foundation (EPF) in Azerbaijan in 2007–2008. This aim of this program was to build productive relationships among religious organizations, secular NGOs and local community leaders for engaging in constructive dialogue to address issues facing their communities. Despite attempts by the US Embassy in Baku and EPF to reach out to the government and the CMB to acquire their support, no large-scale cooperation ever occurred. We determined that CMB leadership had been very opposed to foreign and especially Western attempts to ‘democratize’ Azerbaijan, presumably by manipulation through Islam, and probably saw an anti-government conspiracy in this program. The government’s reluctance to cooperate was a crucial sign for the CMB leadership to formulate such a position. This case is demonstrative of CMB’s operational status and complete dependence on the state.

The CMB’s quietist and completely pro-governmental position negatively affected young religious people, who disagreed with the status quo and considered the CMB ‘hypocritical’ and of no value for Islam and Muslims. Liberal as well as nationalist opposition and protesting youth also saw this institution as a Soviet relict, serving the interests of the government but not society as a whole.

With the spread of religious knowledge among the population resulting from an Islamic revival, many religious Muslims (both Shia and Sunni) came to understand that there was no formal place for the CMB in Islamic religious doctrine and law and that it was rather an institution historically imposed by Russia to control Islamic activism. Religious Muslims follow teachings and rulings by prominent Islamic scholars from abroad as the only legitimate sources of emulation. Indeed, none of the CMB clerics have the necessary status and recognized authority to issue a fatwa, a ruling on a point of Islamic law. Furthermore, according to some experts, Azerbaijan’s official Muslim clergy represented by the CMB has a reputation for low levels of religious knowledge; the CMB is thus not seen by religious Azerbaijani Muslims as a trustworthy Islamic institution or source for reference in religious matters (Yunus 2012).

The government subsequently came to the rescue, given the common interests of the state and the CMB. The new law on Freedom of Religion of 2009 and related legislative amendments made it more complicated for independent Islamic communities that are not approved by the CMB to actually operate and compete with the official clerics. The law also restricts independent religious education, limits religious activity to approved venues, forbids any religious preaching by non-residents as well as residents educated abroad without state permission, etc. The attempts of the government to get full control of Islamic activism increased the status and value of the CMB, allowing it to monopolize this area.

Conclusion

Given the history and underlying philosophy of the major formal Islamic institution the CMB, it would be naive to believe in any independent contribution to the democratization of Azerbaijan. It follows the lead of the authorities and has never produced any different or independent position as far as state building and democratization are concerned.

During its most active phase in the 1990s and early 2000s, Islamic revival in Azerbaijan produced a new range of independent actors who undermined the role and prestige of the CMB. Rising religious awareness of Azerbaijani Muslims also helped to question the doctrinal validity of this institution. However, along with the strengthening of the state, a more centralized approach to the religious sphere emerged, requiring the cooperation of the CMB and its leader, Sheikh-ul-Islam Allahshukur Pashazade. The latter, an influential person in Azerbaijan’s political establishment, has the necessary potential for engaging in the state-building process.

The CMB has become stronger institutionally in recent years and may continue to do so in the future. Given that all Islamic actors understand that they cannot ignore its influence and must cooperate to be able to operate in existing spaces of opportunity, it is likely that the status of the CMB will increase in importance. Therefore, including the CMB in public and political debates, if they take place, could help the institution broaden its perspectives and increase its significance while also turning it into a valuable asset for the democratization process due to its potential to influence Azerbaijani society and impact the country’s political agenda in the long term.

Further Reading

- Aliyev, F. (2004) Framing Perceptions of Islam and the ‘Islamic revival’ in the Post-Soviet Countries, Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, No. 7.spring 2004, ISSN 1583-0039. Romania

- Aliyev, F. (2007) Islamic Revival in Azerbaijan: the Process and Its Political Implications, “The Caucasus and Globalization” journal, Caucasus Center for Strategic Research, Azerbaijan and Sweden, Vol. 1 (2) 2007

- Motika, Raul. (2001) Islam in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Archives De Sciences Sociales Des Religions (web-site) <http://www.ehess.fr/centres/ceifr/assr/Sommaire_115.htm>

- Saroyan, M. (1997) Minorities, Mullahs, and Modernity: Reshaping Community in the Former Soviet Union.University of California, Berkeley Institute.

- Swietochovski, T. (2002) Azerbaijan: the Hidden faces of Islam. WORLD POLICY JOURNAL: Volume XIX,No 3, Fall 2002

- Yunus, Arif (2012) Islamic Palette in Azerbaijan, Adiloglu, Baku 2012

About the Author

Dr. Fuad Aliyev is an adjunct faculty member at Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy (ADA) University in Baku. His research and teaching expertise focus on Islam in post-Soviet countries and Islamic political economy.

The Orthodox Church in the Democratization Process in Georgia: Hindrance or Support?

By Salome Minesashvili (Freie Universität Berlin / Georgian Institute of Politics, Tbilisi)

Abstract

Some changes within the democratization process in Georgia have challenged long-held beliefs and traditions in the society and have often become the subject of public debate, which powerful groups seek to influence. The Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) is one such group. Repeatedly named as the most trusted institution in the country, the GOC’s stance on democracy-related issues and reforms has already impacted political decision-making on a number of occasions. This immense power gives the GOC the potential to enhance democracy, or, on the contrary, to significantly inhibit it if it so desires. This paper analyzes the attitudes, values and behavior of the GOC in the context of their compatibility with democratic values and explores the potential to engage the GOC in the reform process as well as to include it in public and political debates.

The GOC: Influential Institution in the Country

Within Georgia’s fragile division of church and state, the role of the influential Georgian Orthodox Church has become all the more important for the country’s democratization process. The GOC is capable of not only disseminating its position throughout society but also, to some extent, influencing the political agenda.

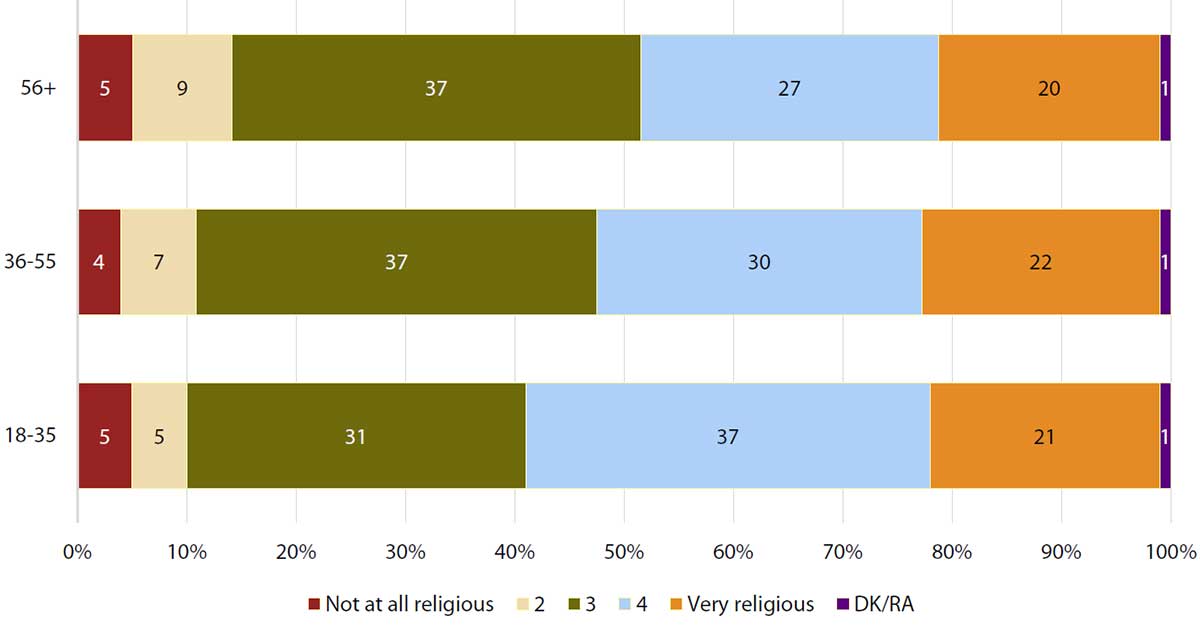

The GOC’s authority is based on the Georgian public’s increased religiosity. One of the top five most religious nations in the world, 82% of the Georgian population considers themselves to be members of the Orthodox Church according to the 2015 Caucasus Barometer survey. Of those who view themselves as members of the GOC, 94% believe that religion plays an important role in their lives. Even more telling, the younger generation— aged 18–35—tends to be more religious than people over 35 (see Figure 1).

The GOC’s special status in the Georgian Constitution adds to its role. In 2002, the Georgian Orthodox Church was granted multiple privileges, including exemption from tax, under an agreement known as the Concordat. The deal extended to education and culture and outlined the state and the Church’s obligation to “jointly care” for the country’s cultural heritage. In addition, if schools or other educational institutions opt to teach Orthodoxy, it is the GOC’s prerogative to set the agenda and select the teachers. The GOC has signed subsequent agreements with the education and justice ministries to implement the powers set out in the Concordat.

The GOC and Democratic Values: Level of Compatibility

Due to the GOC’s high degree of authority, it can either significantly contribute to or hinder democratization. The Church may be divided about different aspects of democracy; however, most of the traditional values that it holds in high esteem clash with the idea of liberal democracy.

The Georgian Orthodox Church primarily exercises influence through its discourse on national identity, which gives excessive emphasis on traditions and customs within the confines of the Orthodox faith. For instance, Patriarch Ilia II proposed that the national values defined by the famous Georgian public figure Ilia Chavchavadze, motherland, language, and religion, be reformulated as God, motherland and human, thus establishing religion as the number one criterion to define nationality. Thus, the GOC’s version of the national ideology is rather exclusive in the sense of making Orthodoxy the primary characteristic of Georgianness. Although non-ethnic Georgians who suffered for Christianity in Georgia, such as the martyrs Shushaniki (Armenian) or Saint Abo (Arab), are also considered to be Georgian, “those Georgians who lead non-Christian ways cannot be part of the Georgian idea”. Correspondingly, the Church understands the foundation of “Georgianness” to be based on two pillars: spiritual values (Christianity and customs) and national-cultural values.

Based on the idea of Orthodoxy as a unique civilization and privilege, the GOC seeks a privileged status in the religious landscape in Georgia. As the Patriarch stated in 1997, “only the Orthodox Church maintains the true and original teaching of Christianity”. In this context, even though the GOC acts in the name of the Georgian people, it represents the majority as only one religious group. In 2011, Patriarch Ilia II protested against an amendment to the civil code that gave religious minority groups the right to register as legal entities under the public law. The Church condemned the law, stating that the amendment was at odds with the interests of both the state and the Church. In cases of religious conflict with local Muslims, for example in Nigvziani, Tsintskaro and Samtatskaro in autumn 2012, the Church not only monopolized the situation, but the agreements it initiated breached the rights of religious minorities according to the Human Rights Education and Monitoring Center (EMC).1

In general, the GOC claims that it does not oppose democracy as such. However, it maintains an ambivalent linkage between the notions of liberalism and democracy: according to the Patriarch, “liberalism without the right religious and national ideology” is considered to be a bearer of “pseudo-democracy” and a threat to the country. In the Georgian context, the GOC believes that some pro-Western politicians are acting against the unique essence of the Georgian nation in the name of democracy. Therefore, the GOC promotes religious nationalism, which is seen as the only path for the survival of the Georgian nation. This view means that the rule of law is considered important only insofar as it is based on a moral agenda. As the Patriarch stated in 2014, “The government should bear in mind that adopted state laws should not oppose the sacred laws”.

In general, the idea of liberalism is looked at rather critically by the Church. Postmodernism, as the GOC calls it, is defined by the Church as total freedom, i.e., allowing any type of action, an idea that is unacceptable for Christianity. This position provides the foundation for the GOC’s attitudes and the values it promotes, including intolerance for sexual minorities and gender equality. On May 17th, 2013, a violent attack led by clergymen against fifty activists who had gathered to rally in support of the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia is one such example. Yet another example occurred in 2014, when the GOC actively opposed the adoption of an Anti-Discrimination Law. Members of the clergy even personally engaged in parliamentary plenary meetings, arguing that equal rights for sexual minorities and gender equality were contrary to moral principles.

The GOC sees its role as the protector of the Georgian nation as a whole under the umbrella of Orthodox Christianity. That view means that the Church’s main responsibility encompasses all of society and supersedes the idea of individual salvation. This perspective is exemplified by the frequent use of collective concepts in the Church’s preaching. For example, the idea that the notion of family is the basis for the Georgian nation means that concepts such as gender equality and equality for sexual minorities are a threat that could potentially undermine the nation.

The Georgian public has repeatedly expressed a high level of trust in the Church, which empowers its narrative as an institution that can dictate moral standards and customs in society. The GOC’s power to mobilize people was evident during clergy-led demonstrations in 2011 and 2013—and the impression was strengthened when the Patriarch’s appeal for calm was enough to send the protesters home. At times of societal conflict, the Georgian people side with the Church. Surveys conducted after the 2011 protests show that after the clergy-led demonstrations, 80% of the population that was aware of the amendment supported the idea that the Parliament should have consulted the Church before adopting the law. This trend indicates that the Georgian public is torn between the notions of democracy and tradition, which are presented in religious discourse as being at least partly in opposition to each other. Whereas Georgians widely support the notion of democracy, at the same time, democracy is not unconditional: Surveys by the Caucasus Research Resource Centers (CRRC) have found that when democracy-linked values clash with traditions, respondents expect the government to prioritize the traditions at the expense of freedom. For example, a majority of voters supported the idea that the government should restrict the publishing of any information that contradicts traditions.2

However, the matter of compatibility between democracy and the GOC’s values is not that straightforward. Quite often liberalism, which is perceived as a vehicle for non-Orthodox values by the Church, is often linked to the West. Nevertheless, the Patriarch has not openly protested against Georgia’s aim to integrate into Western institutions. On the contrary, the Patriarch has several times made supportive statements for advancing relations with the European Union. For instance, in December 2015, when the European Commission launched the visa liberalization process by releasing a report stating that Georgia met all the criteria for a legislative proposal to the European Council and Parliament to lift visa requirements for Georgians, Illia II called the occasion “a huge achievement, celebration for the entire Georgian population and Georgian Church among them”.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the GOC leadership also preaches about some political and civic values that can be linked to democratization, including the appeal that each citizen should participate in the lawmaking process as well as the Patriarch’s emphasis on the importance of hard work and education, respect for the state and public order, and care for public property. Concerning the EU, the Patriarch noted the great expectations for benefits from Europe as long as the Georgian culture was also protected. It is apparent that some basic values of liberal democracy clash with the values that the GOC believes are traditional Georgian values; however, there are some aspects of civic and political culture that the Church supports, and this is where its contribution to the promotion of democracy could lie.

Social Involvement of The GOC

In addition to a number of business activities, the GOC is also active on a wide variety of social issues, especially in terms of education, charities and social funds. The patriarchate has founded at least 84 non-commercial legal entities, including four universities, five seminaries, 25 schools, eight social institutions, 16 charity and development funds and 16 cultural and spiritual institutions. These include approximately ten shelters that serve an estimated 1000–1500 children as well as charity centers for elderly people, such as shelters and soup kitchens. The patriarchate also has a center dedicated to social issues, such as rehabilitation for drug addicts, as well as a center for deaf children. In addi tion, the GOC has an agreement with the Ministry of Justice to work with people on probation and released prisoners, who the Church employs in activities such as church building.

However, the lack of budget transparency makes it difficult to assess the extent of the Church’s charitable works. For the past four years, the Church has received 25 million GEL from the annual state budget. One of the few reports available3 indicates that more than 50% of the budgetary transfer has been spent on religious education. However, the report is not detailed or well documented. On the other hand, of the municipal funding that the Church also receives, only 1% is spent on social projects, 19% is spent on construction and decoration of the churches and 8% is spent on the purchase of religious objects. The rest is not documented.

This lack of information makes it difficult to comprehensively assess the GOC’s social activism, but it is certainly engaged in such activities. Such activities also support some of the democracy-related values, and the Church’s still rather ambivalent political position toward the West could potentially serve as a starting point for involving the Church in the democratization process.

Conclusion

It is apparent that some aspects of the GOC’s ideology ostensibly contradict, rather than encourage, principles of liberal democracy. The Church’s high level of authority and strong position in Georgian society, however, mean that it is imperative for it to engage in democratization processes. Instead of isolating the GOC from these development processes, the Church must be included in such a way that yields a positive contribution to the process. The Church has tremendous power to shape people’s opinions as well as to organize collective action, which can result in community-level changes. First, it is essential to maintain open lines of communication with the Church and its leadership, principally in order to inform and engage the institution in discussions that foster mutual understanding about the importance of democratic values. The Church supports some political and civic values that can contribute to democratization, and it is already involved in multiple social projects. This provides an opening for governmental but also civil society actors to engage the Church in activities that contribute to democratization processes.

Notes

1 EMC. (2013, December 5). Crisis of secularism and loyalty towards the dominant group. EMC Report. Available at: <http://emc.org.ge/2013/12/05/913/>

2 CRRC. (2015, November 12). Nine things politicians should know about Georgian voters. Social Science in the South Caucasus. Available at: <http://crrc-caucasus.blogspot.hu/2015/11/nine-things-politicians-should-know.html>

3 EMC. (2014). The practice of funding religious organizations by the central and local government. Available at: <http://emc.org.ge/2014/10/08/the-practice-of-the-funding-of-the-religiousorganizations-by-the-central-and-local-government/>

Further Reading

- Kakachia, K. (2014 June). Is Georgia’s Orthodox Church an obstacle to European values? PONARS Eurasia policy memo: 322. Available at: <http://www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/georgia%E2%80%99s-orthodox-church-obstacle-european-values>

- Grdzelidze. T. (2010) The Orthodox Church of Georgia: challenges under democracy and freedom (1990– 2009). International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church Volume 10, Issue 2–3, 2010 p. 160–175

- Gavashelishvili. E. (2012) Anti-Modern and Anti-Globalist Tendencies in the Georgian Orthodox Church. Identity Studies. Vol. 4. Available at: <http://ojs.iliauni.edu.ge/index.php/identitystudies/issue/current>

- Janelidze, B. (2015). Secularization and desecularization in Georgia: state and church under Saakashvili government. In Agadjanian, A., Jodicke, A. and Zweerde, E. (eds.). (2015). Religion, nation and democracy in the South Caucasus.Routledge: New York.

- Kekelia, T., Gavashelishvili, E., Ladaria, K. and Sulkhanishvili, I., 2013. “A Role of Georgian Orthodox Church in Forming Georgian National Identity” (martlmadidebeli eklesiis roli kartuli natsionaluri identobis chamokalibebashi). Tbilisi: Ilia State University.

- Ladaria, K., 2012. Georgian Orthodox Church and political project of modernization. Identity Studies, volume 4.

Figure 1: How Religious Would You Say You Are? (%, 2015)

About the Author

Salome Minesashvili is a doctoral candidate at Freie Universität Berlin and a researcher at the Georgian Institute of Politics.

The Armenian Apostolic Church and the Challenges of Democratic Development in Armenia

By Narek Mkrtchyan (Yerevan State University /American University of Armenia, Yerevan)

Abstract

This paper aims to analyze the role of the Armenian Apostolic Church in democratization processes in the Republic of Armenia. The narrative of the first Christian nation and the Armenian Apostolic Church has historically played an important role in shaping the identities (e.g., national, political and cultural) of the Armenian nation throughout history. Taking this fact into consideration, the contribution proposes that the Armenian Apostolic Church, as one of the most trusted institutions in Armenia, has real potential to impact the country’s political decision-making processes. To this end, it is quite important to focus on the relationships among civil society, political elites and the Church. This approach will shed light on the limitations of the Armenian Apostolic Church in supporting the democratization of Armenia. Regarding the relationships between political society and the Church, one can conceptualize such relationships as hegemonic. The Apostolic Church plays an important role in establishing and supporting the hegemony and legitimacy of the ruling regime, which makes them loyal to each other’s policies and ideologies. Next, the contribution will attempt to understand the attitude of the Apostolic Church toward civic activism or civic actions against the ruling regime and vice versa.

Introduction

The Armenian Apostolic Church has historically been an inseparable part of Armenian society and the national narrative, and it is the only institution in the Armenian reality that has preserved its continuity since the 4th century A.D. The collapse of the Soviet Union opened new channels for the re-engagement of the Armenian Apostolic Church in different spheres of society. The privileged status of the Church is justified by its historical role in the maintenance of an Armenian national identity during critical periods of history. However, the engagement of the Armenian Apostolic Church could hardly be possible without official approval from or cooperation with the ruling authorities. This paper aims to shed light on the opportunities and challenges for the Armenian Apostolic Church in the democratization process of the Republic of Armenia. However, it is even more important to understand whether the Church even wants to support democratization. One of the most important aspects of the country’s democratization concerns the development of civil society and civic activism. This contribution particularly tries to examine the role of the Church in the democratization of the Republic of Armenia through the prism of civil society studies. In this context, it is interesting to consider the nature of the relationships among the Church, civil society and political players during the investigation.

The political puzzle of explaining the role of the Church in democratization processes necessarily leads to questions concerning international and domestic legal frameworks. In the context of a religio-political puzzle, it is important to understand what types of legal opportunities religious institutions can provide in supporting different political processes. Nevertheless, much of the current debate centers on only the Armenian Apostolic Church. Next, a legal status examination lends support to the claim that only the Armenian Apostolic Church has the opportunity to play a role in the different political processes.

The State and the Apostolic Church: Mutual Institutions

After proclaiming its independence, the Republic of Armenia signed different international documents protecting the religious freedoms and activities of religious organizations, e.g., the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights. Consequently, the constitution of the newly established Republic was created in accordance with universal standards. Accordingly, Article 8.1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia guarantees “Freedom of activities for all religious organizations”1, which in turn enabled the registration of dozens of religious institutions and churches in Armenia. On the other hand, the Armenian Apostolic Church is the only religious institution whose relationship with the state is regulated by the 2007 law “On the Relations between the State of Armenia and The Holy Apostolic Church of Armenia”. Indeed, this law is based on the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia, according to which “The Republic of Armenia recognizes the exclusive historical mission of the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church as a national church, in the spiritual life, development of the national culture and preservation of the national identity of the people of Armenia”. Thus, the exceptional role of the Armenian Apostolic Church in maintaining the national identity and culture of Armenians2 is officially recognized. This Church, which has the most followers in Armenia, can play the role of either supporting the hegemony of the existing ruling classes or establishing a new hegemony.3 The idea of hegemony should be understood through the prism of Antonio Gramsci’s theoretical concepts. The cooperation of the Armenian Apostolic Church with the state is a type of cooperation with political society, while the engagement of the Church in democratization processes can materialize, at a minimum, through strict cooperation with civil society. To prove this point, it could be argued that the consequences of cooperation with political society, e.g., the exclusive representation of the Armenian Apostolic Church in the spheres of media, education, culture, security and correctional institutions, prohibits the Church from publicly criticizing corruption, unfair procedures of justice or government policies restricting civic activism in Armenia.

The Apostolic Church as Legitimizer of Political Processes

Before examining the Church’s opportunities to support the democratization process of the Republic of Armenia, I would first like to discuss the obstacles and challenges that democratization faces when seeking the support of the Church. Again, the most serious obstacles concerning the official cooperation between the ruling regime and the Armenian Apostolic Church can be conceptualized as hegemonic, which seriously limits the Church’s engagement in democratization processes.

One of the key components of democracy is the functioning of a representative political system through free and fair elections. Elections should be an inseparable part of any contemporary process of democratization. In this regard, it is extremely interesting to examine the position of the Armenian Apostolic Church in these processes. It is obvious that among the obstacles to democratization in the post-Soviet space are unfair presidential, parliamentary and municipal elections. Here, the question arises whether the leading church, which has millions of followers, can condemn such unfair elections in favor of democratization. To provide a more or less comprehensive response to this question, one can examine the historical experiences of other countries. For example, the Catholic Church in communist Poland played a crucial role in not only forming contrasystems and civil society in support of democracy but also in striving for the establishment of its own hegemony.4 Thus, we can argue that the Polish Church was part of civil society.

The picture is different in the case of Armenia. Since Armenia’s independence, the Apostolic Church has been engaged, directly or indirectly, in political processes. To put it more precisely, the power of the Church functions in the sphere of the legitimization of certain political processes or in the rule of certain leaders and regimes. This practice derives from the Armenian royal tradition, when the Catholicos of all Armenians recognized the power of kings and took part in a king’s coronation ceremony. Similarly, after a presidential or a parliamentary election, be it fair or not, the leaders of the Armenian Apostolic Church must present the official statement of the Holy See. The role of the Church is arguably not restricted to ritualistic and symbolic activities because the blessing of the president of the Catholicos plays a crucial role in providing internal legitimacy for parliamentary and presidential elections.5

Although the Constitution states that “The Church shall be separate from the state in the Republic of Armenia”, some high representatives of the Armenian Apostolic Church still try to influence certain political processes. The most recent case concerns municipal elections held in Vanadzor—the third largest city in Armenia—on October 2, 2016, when three opposition parties won 18 council seats in the 31-member Council of Elders, leaving the leading Republican Party with only 13 council seats.6 However, despite the party’s insufficient number of votes, the ruling Republican candidate for mayor surprisingly won the most votes in secret voting. In response, the three opposition parties decided to boycott the sessions of Vanadzor’s municipal council with the aim of preventing the Council from adopting a different agenda. To resolve this complicated situation, the ruling party “petitioned the Church for help”. The response from the Church came swiftly. During the Christmas Mass, the leader of the Diocese of Gugark, Archbishop Seboug Chouldjian, publicly called on the opposition Vanadzor city council members to cooperate with the Republican Mayor.7 The announcement by the archbishop was highly criticized by the opposition parties, which tried to remind the clergy about the separation between the Church and state.

The Church and Regime-Backed Oligarchs

Another challenge to the Church’s engagement in democratization processes concerns cooperation between regime-backed oligarchs and Church leaders. According to the literary and cultural critic Vardan Jaloyan, the Church has cooperated with oligarchs and some criminal networks to ensure its own continuity because church building in Armenia is in many cases the business of oligarchs engaged in illegal/criminal activities.8 Church-building activities seem to increase the reputations of certain oligarchs during election campaigns. For example, during the re-branding of his discredited reputation in the wake of the 2017 parliamentary election campaign, the ruling regime-backed oligarch Gagik Tsarukyan created a film dedicated to his life in an attempt to win voters to the “Tsarukyan alliance”. The film begins with the scene of a church he built, after which the viewer encounters high praise for the religiosity and glorification of Gagik Tsarukyan’s church-building mission by different high representatives of the Armenian Apostolic Church.9

Another noteworthy example concerns the most scandalous corruption incident of 2013 involving former Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan (Chairman of the Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission) and the archbishop of the Ararat diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church, Navasard Kchoyan, who with the help of the businessman Asot Sukiasyan (currently imprisoned) had registered an offshore company in Cyprus worth approximately 10 million dollars.10 The case was considered to represent the most scandalous corruption allegations of the year and one of the key challenges to Armenia’s economic development and democratization in Freedom House’s Nation in Transition 2014 annual report.11

Church vs. Civic Activism

The jointly shaped polices of the Armenian Apostolic Church and the state can hardly allow the Church to publicly criticize the government for corruption, monopoly and injustice. Taking into consideration the institutional and cultural legacy and the legal status of the Church, the indifferent stance of the Armenian Apostolic Church is problematic for the country’s democratic development. It would be wrong to say that the Armenian Apostolic Church is fully isolated from civil society. Somewhat surprisingly, during many civic protests— especially before or after police attacks on activists— the Church sends its clergy to the location of the protest. One example is the “Electric Yerevan” civic protest in 2015, when priests formed a line with intellectuals to create a human wall between the two conflicting sides. Such an action is similar to a “working visit” that aims to ease the tension between the regime and civil society, or in Gramscian terminology, to form a “historic bloc” between the “oppressors and oppressed”. Thus, the Church’s involvement in civic protests is restricted to its symbolic meaning because there is no single precedent when the Church seized the opportunity to stand up for the interests and rights of civil society. Moreover, this fact is well perceived by Armenia’s citizens. In addition, it was not accidental that during the “Khorenatsi” civil rally in support of “Sasna Tsrer”, who had stormed and held one of the headquarters of the Yerevan Police garrison from 17th to 23rd of July, the public refused the directions of the priests and mediation by the Church. According to Human Watch Report, on 29th of July, 2016, the Armenian police used excessive force against peaceful protesters on Khorenatsi Street,12 during which one could hardly find any clergy in the lines of ordinary citizens. Moreover, when Armen Melkonyan— a priest in the Church’s diocese in Maastricht, Holland—participated in a protest in support of Sasna Tsrer in front of the Republic of Armenia Embassy to the Netherlands, the leaders of the Armenian Apostolic Church relieved him of his pastoral responsibilities.13

After the death of Artur Sargsyan, or “the bread bearer” (Hac Berogh), who had been charged for breaking the police cordon to take food to the members of Sasna Tsrer, dozens of citizens asked the Bishop of Yeghvard to perform a requiem mass in his honor. The “bread bearer” Artur Sargsyan died on March 16th, 2017, during the most active period of the parliamentary election campaign, as a consequence of a hunger strike against the ruling regime. However, the Bishop of Yeghvard refused to perform the ceremony in memory of a civic activist who struggled against the ruling regime. Ironically, the action of this representative of the Church appears to be “reasonable” after learning that Sasun Mikayelyan—the leader of one of the leading opposition parties of Armenia, Civil Contract—was among the organizer-citizens. This case does not represent an exception, as Armenian civil society has previously witnessed the unwillingness of the Church to support civic initiatives. For example, since 2008, the “Save Teghut Civic Initiative”— the longest civic initiative in Armenia to date—has been pressuring the government, i.e., the Ministry of Nature Protection and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, to nullify the approval for the exploitation of the Teghut Mine, which would become the second largest copper-molybdenum mine in Armenia, in order to protect the rich flora and fauna of the forest in Lori marz.14 While the public strictly criticized the government’s grant of a 25-year exploitation license to Armenian Copper Program (81% of ACP shares belong to the Liechtenstein-registered Vallex Group), the leader of the Diocese of Gugark, Archbishop Seboug Chouldjian, during a public debate openly supported the Vallex Group’s right to exploit the Teghut.15

All of the above-mentioned cases seem like a piece of a wood floating on the surface of water because they have much more profound roots. To prepare the grounds for the reproduction of its apparatus, a regime will usually use the most trusted institutions in the society. In other words, the creation of hegemony requires the formation of consent in a society. Hence, to create a sense of commonality among civil society, the government uses the potential of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The process of hegemony formation in Armenia involves several key social and state institutions, e.g., schools, the army and prisons. Starting in 2003, a new subject called History of the Armenian Church was taught in all Armenian public schools, and content analyses of the textbook argue that it propagates both the Christian doctrine of the Apostolic Church and the general principles of the state ideology.16 Moreover, the Apostolic Church of Armenia not only participates in society’s primary socialization processes but also supports national security. The securitization mission of the Church was established in a 2000 charter signed by the Apostolic Church and the government, according to which priests are allowed to regularly hold meetings with soldiers in order to provide Christian-patriotic education. In addition, the Armenian Apostolic Church is the only religious institution the country that has the right to hold regular meetings with prisoners in correctional institutions. This is another important process that supports the hegemony of the regime through the formation of a historic bloc between the oppressors and the oppressed. As a pay-off for the services of the Church, in 2011, the Parliament of the Republic of Armenia approved legal amendments that exempted the Church—one of the largest landowners in the country—from property and land taxes. Thus, there is ample reason to understand the Church’s supportive attitude toward political society.

Conclusion

To sum up, the Armenian Apostolic Church has real potential to mobilize society toward certain political processes. In practice, the Church can play huge role in democratization or the democratic decision-making process in the Republic of Armenia only after overcoming the abovementioned challenges. However, the mutually beneficial high-level cooperation with political society prevents the Church from being an active supporter of democratization, at least on the civil society level. The Church can support the democratization of the Republic of Armenia first of all by its willingness to do so. Next, the ruling regime must stop perceiving the Church as a voter mobilizer, policy legitimizer and hegemony supporter.

Notes

1 National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia (1991), The Law of the Republic of Armenia on the Freedom of Conscience and on Religious Organizations. <http://www.parliament.am/legislation.php?sel=show&ID=2041&lang=arm>

2 A similar pattern emerged for the Georgian Orthodox Church when the state by Constitutional Agreement simultaneously recognized the special role of the Orthodox Church in Georgia and freedom of belief and religion.

3 See Narek Mkrtchyan (2015), Gramsci in Armenia: State–Church Relations in the Post-Soviet Armenia, Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies, (2015) 32(3), p. 166.

4 Eugeniusz Górski (2007), Civil Society, Pluralism and Universalism, Polish Philosophical Studies, VIII. Washington DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, p. 25.

5 Narek Mkrtchyan (2015), op. cit., 167.

6 “Bright Armenia” party to initiate dissolution of Vanadzor Council of Elders, Panorama.am, <http://www.panorama.am/en/news/2016/12/13/“Bright-Armenia”party-to-initiate-dissolution-of-Vanadzor-Council-of-Elders/1693713>

7 Nare Stepanyan, “The spiritual leaders should not intervene political processes” Azatutyun, <http://www.azatutyun.am/a/28218918.html> last view 10 March. (In Armenian).

8 Vardan Jaloyan, The Church and Mafia, <http://religions.am/article/եկեղեցին-և-մաֆիան/> last viewed 1 April, 2017. (In Armenian).

9 “Մարդ, որը կառուցում է”. Գագիկ Ծառուկյան Մաս 1-ին [The man who constructs: Gagik Tsarukyan, Part 1] <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M8ii19eopyE>

10 Ararat Davtyan, Edik Baghdasaryan, and Kristine Aghalaryan, “Cyprus Troika: Who ‘Stripped’ Businessman Paylak Hayrapetyan of His Assets?” Hetq, 29 May 2013, <http://hetq.am/eng/news/26891/ovqer-en-paylak-hayrapetyani-unezrkmanhexinaknery-ofshorayin-eryaky.html> last view 8 April, 2017.

11 Nation in Transition 2014, Armenia, <https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/armenia>

12 “Armenia: Excessive Police Force at Protest” Human Rights Watch <https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/08/01/armenia-excessivepolice-force-protest>, accessed on April 9th 2017.

13 Armine Sahakyan, “Priest’s Complaint About Armenian Government Strikes a Chord With the Faithful” Huffington Post, <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/armine-sahakyan/a-priestscomplaint-about_b_11810286.html>, last view 9 April 2017.

14 For more details, see Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan, Valentina Gevorgyan, Civic Activism as a Novel Component of Armenian Civil Society, Yerevan 2016.

15 Գուգարաց թեմի առաջնորդի խոսքը, [The speech of the leader of the Diocese of Gugark] January 17th 2012, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ly9vxJHxb64>. 16 See Narek Mkrtchyan (2015), op. cit., 169.

Further Reading

- Yulia Antonyan (2014) Political power and church construction in Armenia. In Agadjanian A, Jödicke A, van der Zweerde E (eds) Religion, nation and democracy in the south Caucasus. New York: Routledge, 81–95.

- Jose Casanova (1994), Public religions in the modern world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Narek Mkrtchyan (2015), Gramsci in Armenia: State–Church Relations in the Post-Soviet Armenia, Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies, (2015) 32(3), 163–176.

- Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan, Valentina Gevorgyan, Civic Activism as a Novel Component of Armenian Civil Society, Yerevan 2016.

About the Author

Narek Mkrtchyan is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of World History at Yerevan State University. Currently, he is a visiting lecturer at American University of Armenia. His research interests focus on Armenian and world history as well as nation and state building in the post-Soviet space.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.