Russian Analytical Digest No 211: Thinking about the Revolution: Perspectives on Russia between Stability and Revolution

20 Dec 2017

By Natasha Kuhrt, Ruth Deyermond and David Lewis for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 12 December 2017.

1917 in 2017: a ‘Useless’ Past? Remembering and Forgetting the Bolshevik Revolution

By Natasha Kuhrt (King’s College, London)

Abstract

For Russia, the centenary of the 1917 revolution is an event fraught with difficulty. It was an event not only of significance for Russian domestic politics, but one that reverberated across the globe. The ideals of the Bolshevik Revolution are today hard to defend: the revolution gave birth to an ideology that is now roundly condemned. Furthermore, the various ‘colored revolutions’ in the former Soviet space, have highlighted the Kremlin’s deep disquiet regarding revolutions, and reconfirmed the view that revolutions only lead to chaos and instability. It is therefore imperative for the current regime to emphasize its role in maintaining stability.

Ernest Renan has suggested that people need not only to be able to remember their common past, but also to forget divisive events, whose memory would only serve to reproduce old conflicts in present-day society. For Russia, the centenary of the 1917 revolution is an event fraught with difficulty. It was an event not only of significance for Russian domestic politics, but one that reverberated across the globe. For that reason the marking of this event has been taking place not only in Russia, but also in countries across the globe. In many ways there is more interest outside Russia than within Russia itself. Putin recently noted the ambiguity of the revolution for Russia: the ambiguity certainly makes the revolution difficult to incorporate into current Russian national identity and ‘official’ nationalism.

Other revolutions, notably the French Revolution, have also had global resonance. Yet the ideals of the French Revolution, liberté, égalité, fraternité, continue not only to provide the bedrock for the French nation-state, but also link to universal values such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Of course, the Bolshevik revolution was also based on universalistic, utopian ideals that inspired movements around the world. Yet the values of the Bolshevik Revolution, while similarly universalistic, can be hard to defend.

Furthermore, the various ‘colored revolutions’ in the former Soviet space, starting with the ‘Orange’ revolution in Ukraine in 2005 have highlighted the Kremlin’s deep disquiet regarding revolutions –in particular those which are seen to be orchestrated or encouraged by external forces and that end in ‘regime change’. Subsequently, the Arab revolutions reconfirmed the Kremlin’s view that revolutions result in chaos and instability.

In commemorating events someone must select the events to be remembered, and those which are to be forgotten, although it is clear that some events will resonate more than others, and often from a ‘limited repertoire’: Russia has a particularly limited repertoire of national narrative on which to draw.

Commemorative events are usually staged as political rituals and public pageantries loaded with symbolism, and serve as focal points for identity reaffirmation, providing multi-layered meanings to states and societies about a certain historic event or issue. However, not all groups within societies nationally or regionally equally welcome that commemoration (e.g. Holodomor 2008). Furthermore, over time there may be a change in the social meaning of the event to be commemorated.

What Interpretation of the Revolution are the Authorities ‘Pushing’?

Vladimir Zhirinovsky has suggested that the February revolution was planned similarly to the ‘Orange Revolution’ (Ukraine 2004) where workers were, in his words, ‘paid to strike’; and the ‘revolution’ was in reality a ‘coup’ directed from abroad. Rejecting the notion of the 1917 events as popular uprisings, Professor Elena Ponamareva suggests that the aims and objectives of the 1917 revolution were identical to those of ‘colored revolutions’, i.e. it was a case of ‘regime change’.

Much of the Russian media has used the centenary as an opportunity to rebuff any suggestions that today’s Russia might be ripe for revolution, and some note that while the West in particular, might be hoping for revolution in Russia, because of predictions of an economic downturn, a revolution is in reality highly unlikely. The counter-narrative is that Russia has rarely been more stable than it is today. ‘Stability’ has been a leitmotif running through Putin’s incumbency. It is imperative for the current administration to present itself as the guardian of stability, indeed its legitimacy to some extent rests on its continued ability to maintain it. Putin criticizes the Bolsheviks who ‘wished to see their fatherland defeated (Brest-Litovsk) while heroic Russian soldiers and officers shed blood on the fronts of the first world war’. For Putin, the revolution caused Russia as a state ‘to collapse and declare itself defeated’.

One article entitled ‘Why there will be no revolution in Russia’, interviewed workers in St Petersburg at the exact locations where revolt broke out in February 1917: for example at one factory, each worker explains in turn why they would definitely never join a revolution today. The centenary is thus used as an opportunity to argue against predictions of unrest in today’s Russia: for example responding to the suggestion that Russia would see outbreaks of popular protest against the current regime, the TV show host Vladimir Soloviev retorted: ‘[U]pheaval can only happen if power hasn’t the will to protect itself and that is what happened in 1917 and 1991. They were due to a coup inside the power around (President) Gorbachev and (Tsar) Nikolai. We don’t have such circumstances today.’ This demonstrates the growing tendency to conflate 1917 and the failed coup of 1991 along with the USSR’s collapse. In Putin’s words, both 1917 and 1991 were ‘national catastrophes of the twentieth century, when we twice experienced the breakdown of our nationhood.’ (Nikitina 2014)

Using the revolution as legitimation for Putin is problematic, given that his regime is to a large extent now based on his role as a bulwark against revolution and regime change. For that reason he needs to continue to emphasize the centrality of stability.

The Revolution as a Divisive Event

Russia is legally the continuer state of the USSR, unlike the other republics, which are merely successor states. Putin has said that the collapse of the USSR was a geopolitical disaster, a tragedy. Yet he has also presented the coming into being of the USSR as a break with the past. Putin seeks to present Russia’s past as an uninterrupted narrative in the longue durée. For Putin, Russia’s current problems are directly caused by these unnatural ‘ruptures’ with the past: ‘[M]any of the serious problems we face have their roots in this. (Nikitina 2014). Russian Minister for Culture, Vladimir Medinskii, in similar vein declared as the real victor of the revolutionary upheavals ‘a third force, which did not participate in the civil war: historical Russia, the same Russia which existed for a thousand years before the revolution and which will continue to exist in the future’.

Thus any problems in today’s Russia can be attributed to the twin catastrophes of 1917 and 1991, rather than to any policies of the current regime. In this sense the revolution acts as a cautionary tale, just as the ‘chaotic 1990s’ similarly act as the obverse of present-day ‘stable’ Russia.

The Shadow of the Past

Contemporary attempts to make a reckoning with Russia’s past are controversial and also seen as leading to instability. Russia has shown itself to be very defensive about Soviet policies, for example, rejecting Ukrainian claims that forced collectivization represents Genocide, proposing that collectivization should instead be seen as a shared tragedy for all people of the USSR.

Existing projects that seek to shed light on Soviet era crimes such as Memorial’s project to map out sites of execution and terror across Moscow, threaten the state monopoly on the national narrative. As Olga Lebedeva notes, ‘in Russian society’s collective memory there is no information about the authors and executors of repressive orders. The state has powerful means at its disposal to construct and attribute values, and consequently, to manipulate collective memory. Today, Russia’s government has little interest in revealing important information about the people responsible for the crimes of the Soviet era.’ (Lebedeva 2016) Putin’s unveiling of a wall to commemorate the victims of Soviet terror might seem to contradict this: however this highlights the fact that such state-organized, top–down approach often aims precisely to stifle and ‘decommission’ the memory of atrocities by recourse to a rhetoric in which the suffering of victims is recognized while the role of the perpetrators continues to be ignored (Adler).

Silence about these crimes from the state is to some extent understandable. Why not then, celebrate the revolution and make it a more central part of the national narrative, given the utopian and sometimes laudable ideals of the revolution? The answer must be that despite the fact that the repressions were at their worst under Stalin, it was Lenin who laid the foundations for this. Memorial is also scrutinizing the early years of Soviet rule. For example, Memorial has revealed the relatively unknown fact that in those first few years following 1917, around twenty concentration camps were set up in Moscow.

The Great Patriotic War as Counterpoint to Revolution and Myth of Common Origin of Post-Soviet Russia

The counterpoint to the revolution, which is a ‘useless past’, becomes the Great Patriotic War. Here we have a unifying and uncontested narrative, one that unites the nation in remembering the suffering and sacrifice of the collective. It further symbolizes a victorious Russia, one that acquired new territories, unlike the revolution of 1917, which entailed withdrawing from the First World War and ceding territories to the Germans by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Second World War narrative encompasses not only Russia as a nation, but also brings together all the nations of the former Soviet Union. Thus celebrating victory in this war is hailed by Putin as the common heritage of former republics of the USSR and now independent states. In recent years however, there is a growing problem of former Soviet republics seeking to contest the common narrative (e.g. the Bronze Solider controversy in Estonia or the partisan issue in Ukraine), but this reinforces Russian national identity as such counter-narratives are rejected as ‘fascist’. The power of the myth of the Great Patriotic War lies in the fact that the whole swathe of unbroken Russian history was invoked by Stalin to galvanize the ‘Russian nation’ against the German invasion.

Disowning the Revolution but Cherishing the Communist State?

The key event in post-revolutionary Russia was the realization that the Bolshevik revolution would not transform the world i.e. that world revolution would not take place. The first Communist state was therefore borne of unrealized ideals, and after the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the idea of co-existence or accommodation with the West emerged. During the Stalinist period the survival of state (ironically, given the fact that the state was meant to wither away under Communism) became paramount, in no small part due to Western resistance to Bolshevism. It is the ‘stable’ Stalinist years that Putin prefers to emphasize, conflating ‘excessive demonization of Stalin’ with criticism of Russia and the USSR.

Conclusion

The dualistic nature of the revolutionary heritage highlights the fact that Russia remains a country that has not fully come to terms with its past. Commemoration may take many forms, and may be enacted by civil society actors or may be a national day or anniversary such as Bastille Day in France. Organizers of such events aim to bring about reflection on the past, but very often they wish to reinforce a particular interpretation of what it means. In Russia’s case a clear official narrative is lacking due to the ambiguity of the revolution and its legacy. Unlike the Great Patriotic War, which provides a ‘usable past’, the revolution is, if not entirely useless, problematic. Furthermore, the status of Communism in many former Soviet bloc countries as a criminal enterprise casts a shadow, while domestic attempts to preserve the memory of past repression and to identify perpetrators raise troubling questions for today’s regime. The current administration tends to portray the revolution, like all revolutions as symbolizing instability, upheaval and division. This is contrasted heavily with present-day Russia, which is depicted as symbolizing stability, unity and predictability. So we are left with the paradox that 1917 created the state of which the present Russian state is the legal successor. Yet in terms of state legitimation the performativity of 1917 remains extremely limited.

Further Reading

Adler, Nanci ‘Reconciliation with—or rehabilitation of—the Soviet past?’ Memory Studies, vol. 5, issue 3, pp. 327–338

Mark Edele, ‘Friday essay: Putin, memory wars and the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution’, February 9 2017, <https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-putin-memory-wars-and-the-100th-anniversary-of-the-russian-revolution-72477>, accessed 21.09.2017

Lebedeva, Olga (2016) ‘Topography of Terror: Mapping Sites of Soviet Repressions in Moscow’, in Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society, vol. 2 (no. 2).

Nikitina, Yulia (2014) The ‘Color Revolutions’ and ‘Arab Spring’ in Russian Official Discourse, Connections: The Quarterly Journal.

Ponamareva, Elena (2017) ‘Pomnit' uroki proshlogo’, 12 February, Izvestiia, <http://izvestia.ru/news/ 664618#ixzz4ZR3UM8u3>, accessed 20.10.2017

Trudolyubov, Maxim ‘The Russian State’s Lost Birth Certificate’, October 31, 2017 (Kennan Institute). <https:// www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/the-russian-states-lost-birth-certificate>, accessed 02.11.2017

About the Author

Natasha Kuhrt is a lecturer at King’s College London, UK.

Russian Opinions about the October Revolution

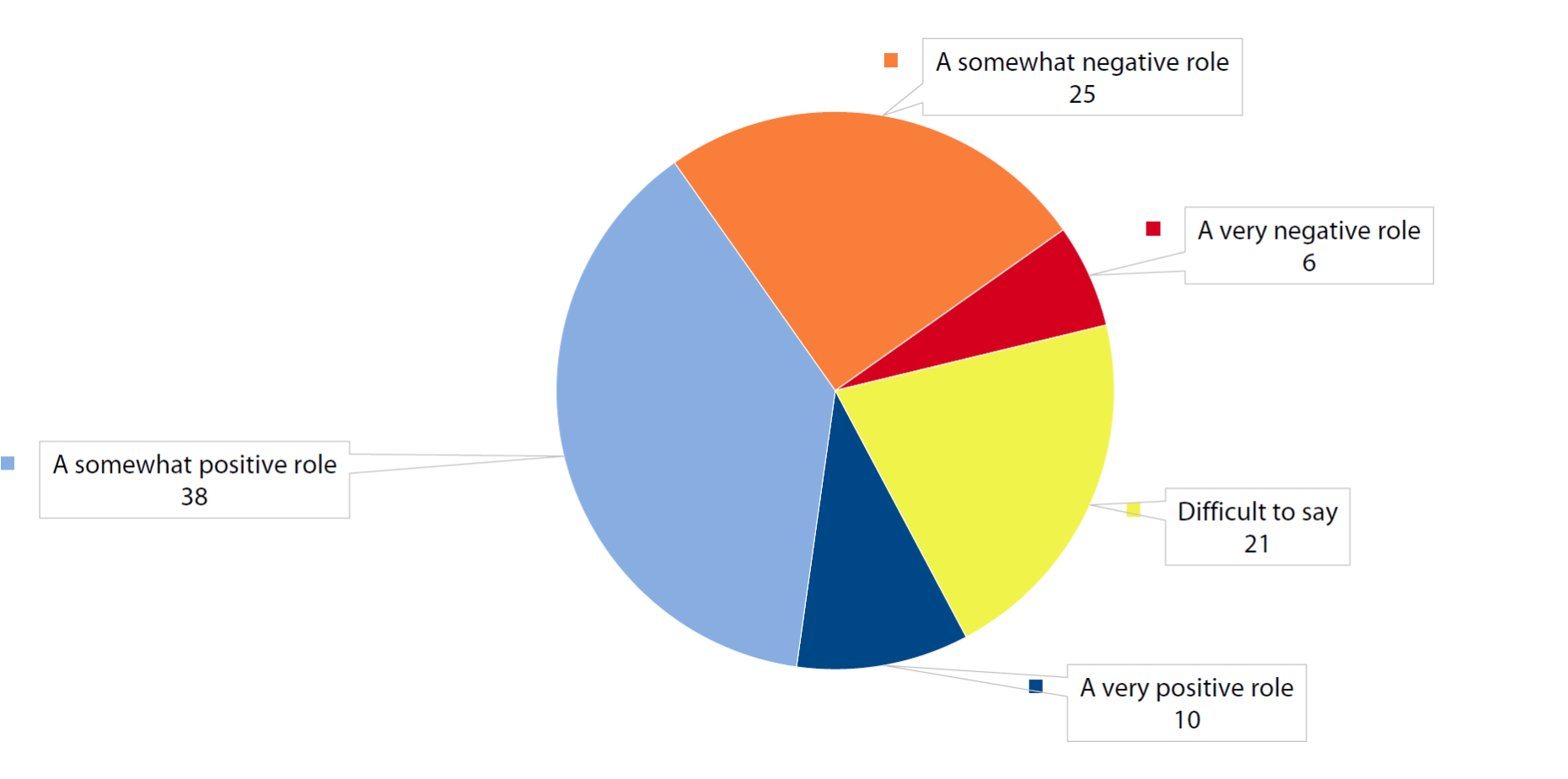

Figure 1: What Do You Think: Did the October Revolution Play a Positive or a Negative Role in Russian History? (in % of respondents)

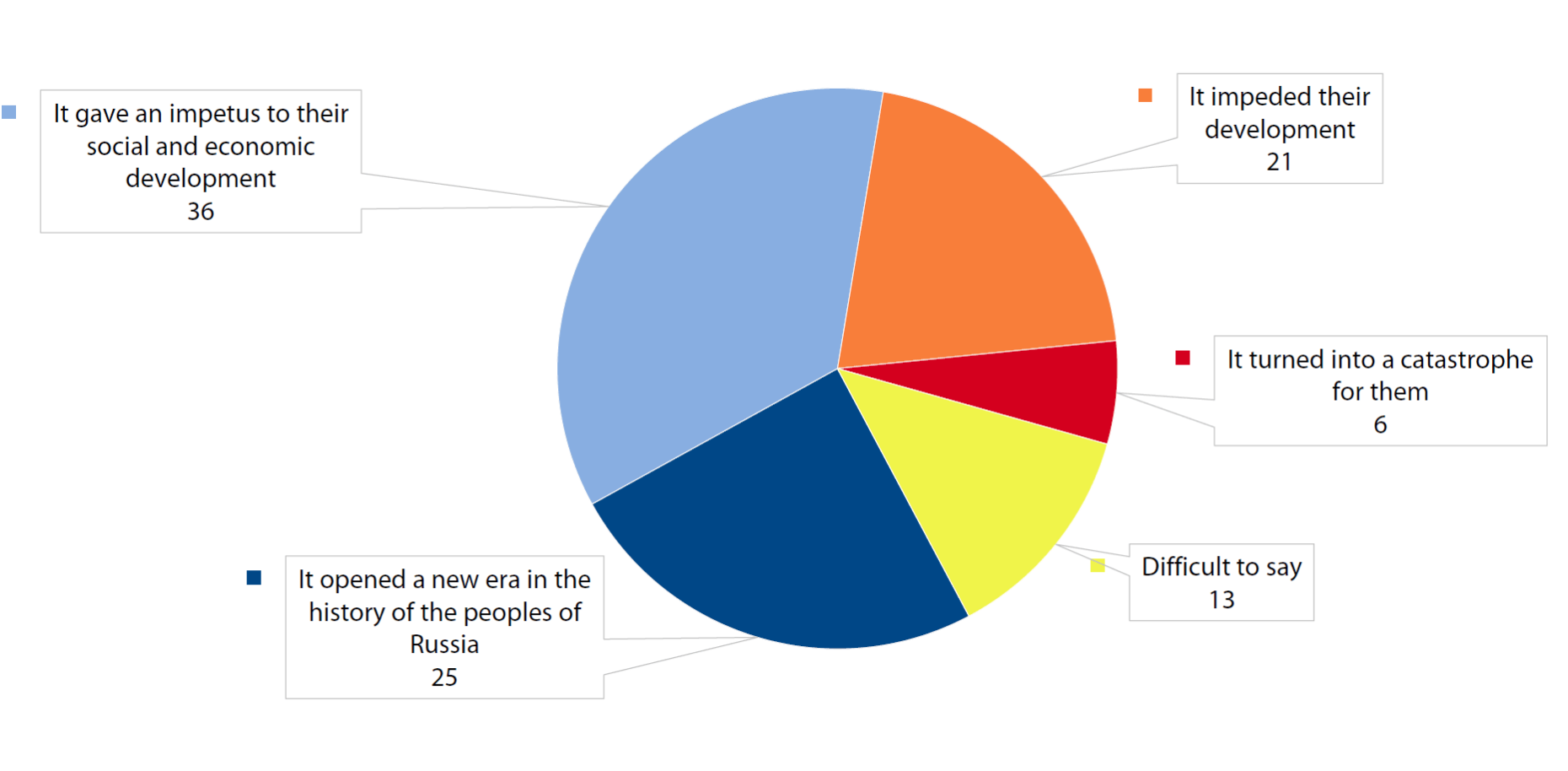

Figure 2: With Which of the Following Opinions about the Consequences of the October Revolution for the Peoples of Russia Would You Be Most Likely to Agree? (in % of respondents)

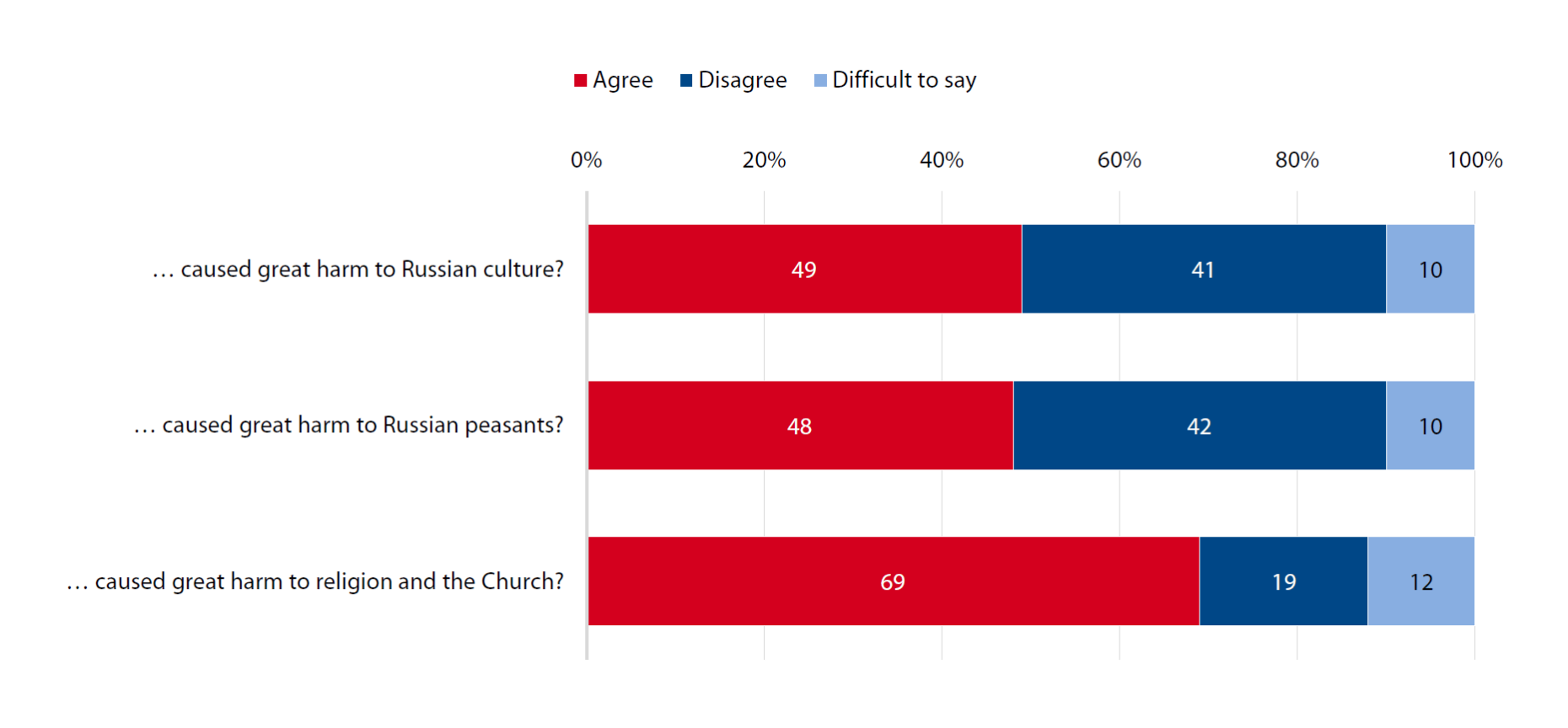

Figure 3: Do You Agree or Disagree That the October Revolution … (in % of respondents)

Figure 4: What Do You Think, Was the Accession to Power in 1917 of the “Bolsheviks” Legitimate or Not? (in % of respondents)

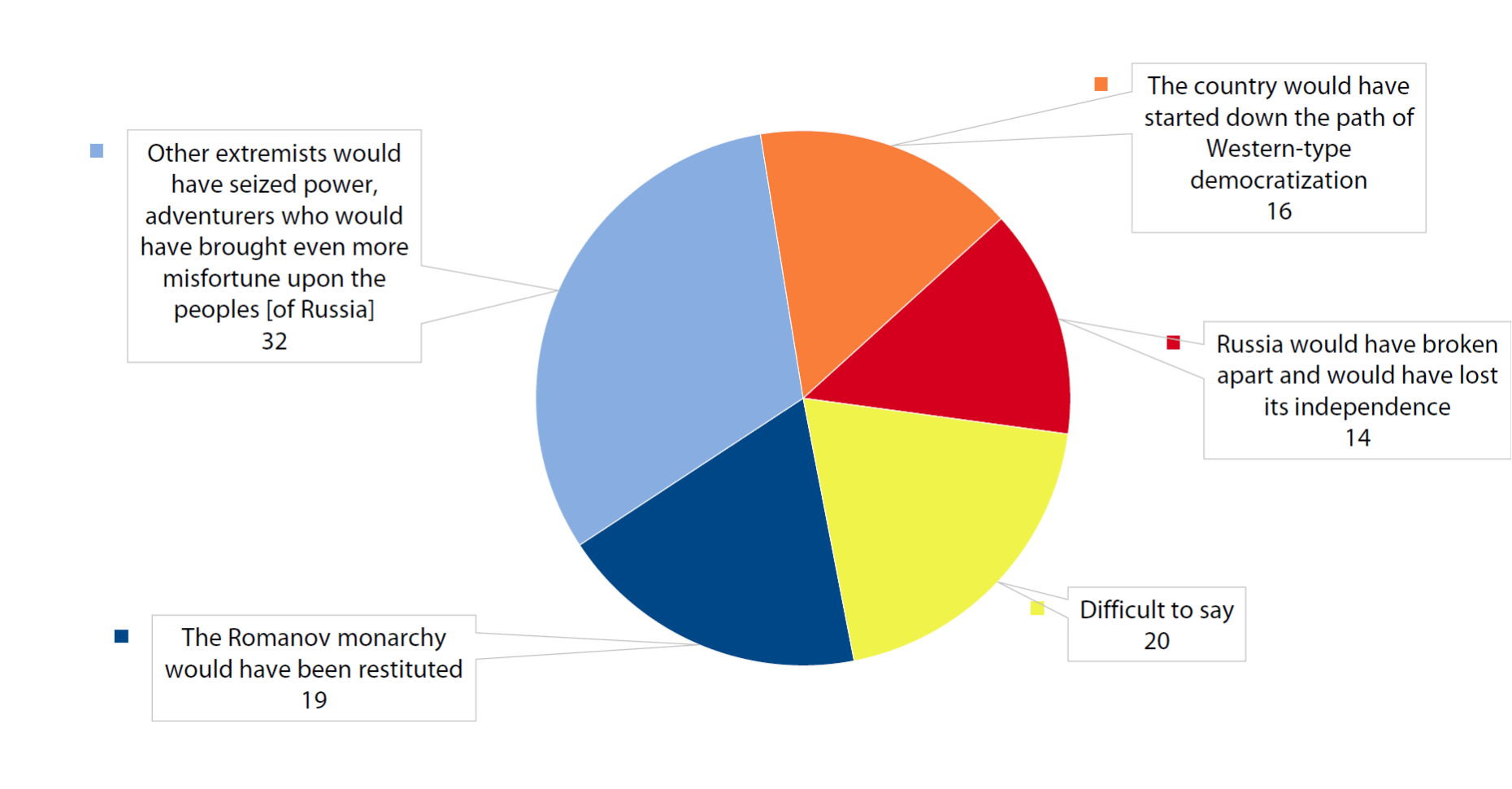

Figure 5: What Do You Think Would Have Happened to Our Country if the Bolsheviks Had Not Seized and Kept Power in 1917? (in % of respondents)

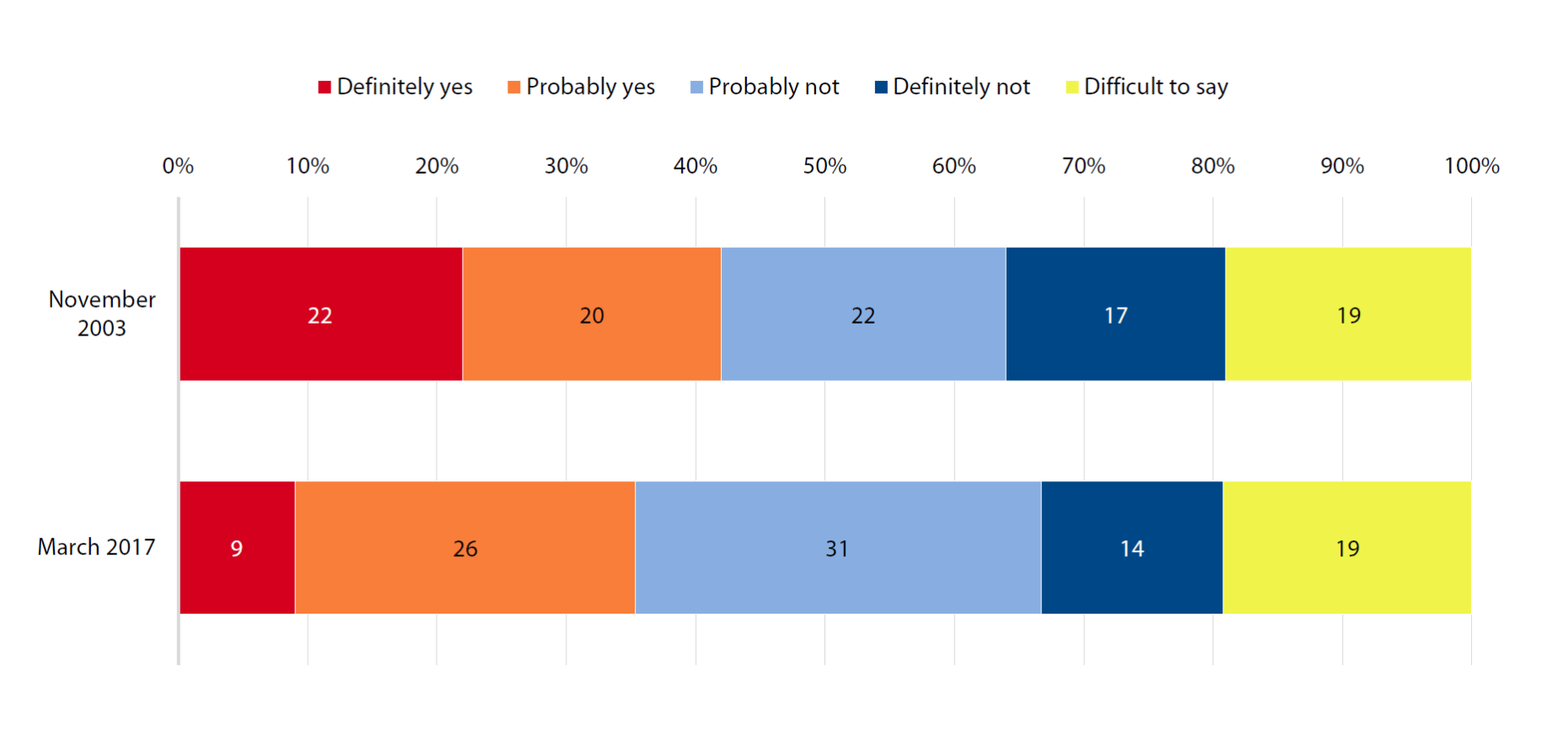

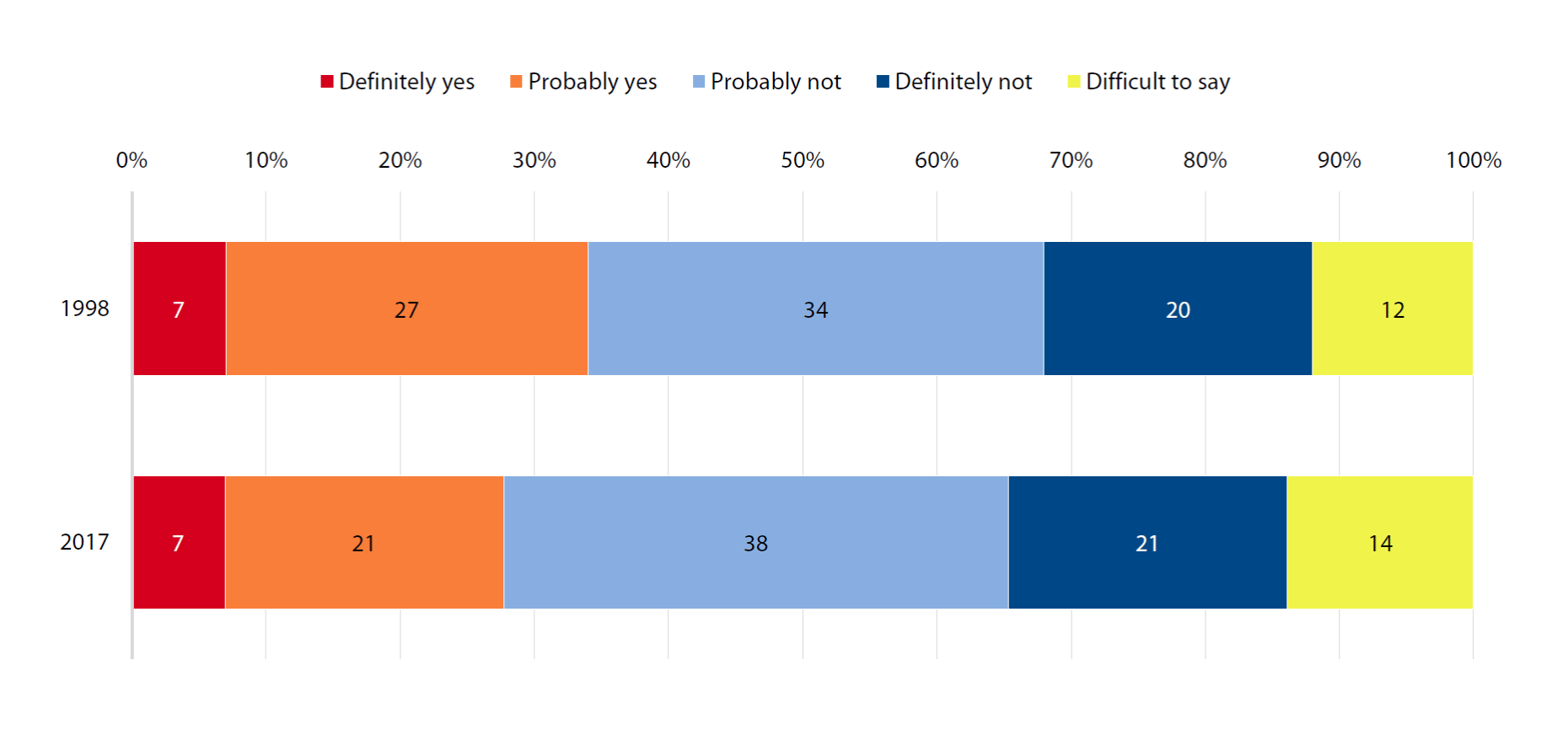

Figure 6: Do You Think That Events Similar to the Events of 1917 Could Happen Again in Today’s Russia? (in % of respondents)

America’s Failed Russian Revolution: How the Trump Administration Tried, and Failed, to Reset US Thinking About Russia

Ruth Deyermond (Kings College, London)

Abstract

For the first quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the legacies of the Bolshevik and American Revolutions shaped the conversation of American politicians about Russia’s political development. This has been challenged by the campaign and presidency of Donald Trump, which have introduced realist and cultural conservative frameworks into the debate about relations with Russia. Ultimately, however, the compromised character of the Trump presidency and the strong attachment of the political mainstream to the Soviet and American revolutionary models means that any sustained shift in the way that the American political elite thinks about Russia is unlikely.

For the first quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US political elite appeared to view Russia through the prism of two events and their legacies: the American and Bolshevik revolutions. For politicians across the political spectrum, the political values associated with the American Revolution appeared to provide a model for the development of the new Russian state, and a standard against which to judge the failures of Russia’s transition to a US-style democracy. At the same time, the Bolshevik revolution and its legacy of totalitarianism and violence appeared to be the only other model of Russian state behaviour in the American elite’s political imaginary. Only two paths were available to Russia, it appeared: forward to the model of politics and society established by the American Revolution, or backwards to the legacy of the Bolshevik Revolution.

In the 1990s in particular, American political elites frequently represented Russia as on the path not only to democracy understood in general terms, but to a democracy of the American type, informed by core US political values and reflecting the political legacy of the American Revolution. President George H.W. Bush repeatedly characterised the radical change of the final months of the USSR as a ‘new Soviet Revolution’ that was moving the country towards the American political and economic model, and he and his advisors spoke and acted in ways that indicated that the USSR, and later Russia, was on a clear path towards this American-style future.

This assumption was even more evident in the language and policies of the Clinton administration whose members, including Clinton himself, repeatedly characterised developments in Russia as part of a process of transition to an American-style democracy of civil society pluralism, a small state, a free market economy, and a political system in which respect for the constitution tempered presidential power. This characterisation persisted in the face of ever more obvious departures from this ideal path: Yeltsin’s deployment of the army against the Russian parliament in 1993, for example, was portrayed as a necessary step towards democracy, and the subsequent parliamentary elections and constitutional referendum were characterised as an important move forward towards a democracy of the American type. When challenged about the Russian government’s conduct of the war in Chechnya, members of the administration invoked the US Civil War, suggesting that the Chechen war was a consequence of Russian democratisation in the way that the US Civil War was a consequence of a similar process in the century after the American Revolution. Elements of this approach, were also evident in the language of the George W. Bush administration until the collapse of the US–Russia relationship in Bush’s second term, with Bush repeatedly claiming that the US and Russia were united by common democratic values and a love of freedom.

Increasingly, however, and certainly in the last decade as the Russian political system has moved in a less democratic direction and relations with the US have declined sharply, the characterisation of the Russian political system by US politicians has reflected a view that Russia under Putin has reverted to the authoritarianism and expansionism of the Soviet model. Parallels between the USSR and contemporary Russia are frequently drawn, in relation both to domestic and to foreign policy, with Russian goals understood to be the reassertion of dominance over the post-Soviet space and beyond, and the destruction of the American way of life. Thus, citing a 1950 CIA report on Soviet foreign policy goals, one Senator suggested earlier this year that ‘Russia’s goals haven’t changed [since 1950]. Russia’s goals are to oppose us, our vision, our values, and our democracy’. Most obviously, the Soviet model is invoked in relation to Vladimir Putin, whose career in the KGB and comment on the ‘geopolitical tragedy’ of the Soviet collapse are frequently cited by Democrats and by Republicans such as Senator John McCain. One Republican Congressman, in a characterisation typical for much of the US political elite, has said that Putin ‘wants to be the leader like Khrushchev or Brezhnev. Really, he would rather be in the nature of Stalin’.

While, for a quarter century, the US political mainstream has often appeared unable to talk about Russia in ways that escaped the confines of these two models, these ideas have faced an unprecedented challenge since 2016, as a consequence of the election of Donald Trump. Seemingly unconcerned about questions of democratic development or reverses in Russia, or the normative questions about Russian foreign policy behaviour, the most prominent foreign policy figures in the Trump election campaign and in the Trump White House, have adopted an entirely different approach to thinking about Russia. Two overlapping sets of ideas about relations with Russia have been evident in the approach of the Trump campaign and administration and in parts of its intellectual hinterland. Both represent a notable break with previous approaches.

The first of these new models, even if not articulated as such, is a variant of the classical realism of International Relations thought. In this view, Russia and the US are both powerful states with interests in a variety of regions and issues. Rather than worrying about normative convergence or divergence, the US needs to embrace a pragmatic partnership with Russia on areas of shared interest, even where the conduct of Russia has been ethically or legally problematic. Thus, a shared interest in combating Islamist terrorism should lead to cooperation on Syria, despite Russian support for the Assad government. Likewise, the Russian interest in lifting the sanctions imposed following the annexation of Crimea is seen to be shared by the US (or at least some sectors of the US economy, notably the energy industry); as a result, a proposal by the Trump administration to lift sanctions despite the unresolved problem of Crimea was widely expected until the developing Russia-related scandal made it impossible. Less discussed than the proposed pragmatic alignment with Russia on sanctions and Syria, this realist approach has also accepted the idea of potential competition in areas where interests are seen to conflict, even on areas of long-established cooperation. In the last 30 years, arms control has generally been a cornerstone of US–Russia cooperative relations, helping to stabilise the relationship even in periods of broader disagreement; even where disputes have occurred, as over US missile defence, they have occurred in a broader climate of bilateral agreement about the need for arms control. Since the 2016 presidential debates, however, Trump has made clear his desire to expand and modernise the US nuclear arsenal, in part because of his concerns about what he regards as the superiority of Russian nuclear forces (as he told a debate audience in 2016, ‘Russia is new in terms of nuclear and we are old and tired and exhausted in terms of nuclear. A very bad thing’).

At the same time as these realist approaches have shaped aspects of thinking about the relationship with Russia, a very different approach has emerged in the broader culture of the nationalist far right from which the Trump administration has derived support and ideas. Unlike the realist rejection of historically-informed values as frameworks for thinking about Russia, some nationalist conservative positions assume shared (conservative) values, which some see as a basis for re-founding the US–Russia relationship. In this view, as alt-right polemicist Alex Jones suggested in a hagiographic interview with Alexander Dugin, Russia and the US share a common enemy in the form of ‘globalists’ who want to force nations to ‘give up their identity’ and to ‘conquer all cultures and destroy them’. Russian and US nationalist conservatives can thus, in this view, find common cause in their efforts to counter the ‘cultural death’ of ‘globalism’ and in their commitment to protecting what they see as traditional values attacked by the forces of liberalism, including the cultural pre-eminence of Christianity, social conservatism, and opposition to LGBTQ equality. This view appears to have found a temporary foothold inside the White House itself; although highly critical of what he described as Putin’s ‘kleptocracy’, Bannon was reported to have spoken admiringly in 2014 about Putin’s ‘traditionalism’ and nationalism and to have asserted that Putin was ‘playing very strongly to [American] social conservatives about his message about more traditional values’. Thus, while many of those currently or previously connected to the Trump White House have talked about the relationship with Russia in realist terms (working together on areas of short-term mutual interest, unencumbered by ethical considerations, but taking a hawkish line on areas of perceived conflict), an overlapping strand of ideas about Russia promotes the idea of shared normative positions in the form of conservative nationalist opposition to the perceived evils of ‘globalism’.

This move away from viewing the American and Bolshevik revolutionary legacies as the only significant models (positive or negative) for understanding Russia’s present and future, and the engagement with both realist positions and far-right ideas about shared conservative values, represents a dramatic shift in US political elite thinking about Russia. However, it is not, as the events of the last year have made clear, a stable or permanent shift, not least because it has not been reflected in the positions taken by other key figures in the US political elite, notably both the Democratic party and prominent figures in the Senate Republican party. The idea of Russia faced with a choice between the Soviet and American models remains dominant in the language of the Democratic party and among many, arguably most, of those Republicans in Congress who are willing to engage with the highly sensitive subject of Russia. As the last ten months have shown, attempts to move to a different basis for US approaches to Russia have foundered on (amongst other things) the seemingly immovable attachment of large sections of the US political elite to a Manichean view of Russia’s political options that has shaped attitudes in Washington for the last twenty five years, as it did for the seventy five years before that.

In these cases, the language on Russia remains grounded in the traditional approaches, portraying the Putin government as a neo-Soviet regime with ambitions to restore Cold War levels of power projection and to destroy American values. In contrast, Russian opponents of the Putin government such as Alexei Navalny and Vladimir Kara-Murza are portrayed as democrats aligned with US political values, as Yeltsin often was in the 1990s. The adherence to this conceptual framework for understanding Russia does not appear to have been weakened by the shift in thinking represented by the Trump administration, and the window for any such broader shift appears to have closed as Russia-related scandal consumes the White House. This intractability and the scandal itself have largely ended the possibility of converting Trump team approaches to Russia into significant policy, as the bipartisan vote to block the president’s ability to lift sanctions against Russia made clear.

As a result, what looked to many people a year ago like a revolution in thinking about Russia has gained little traction, and the twin revolutionary spectres of 1776 and 1917 appear likely to haunt US political rhetoric and limit the scope for policy change on Russia for the foreseeable future.

About the Author

Ruth Deyermond is a lecturer at King’s College London, UK.

US Attitudes Towards Russia Before and After the 2016 US Presidential Elections

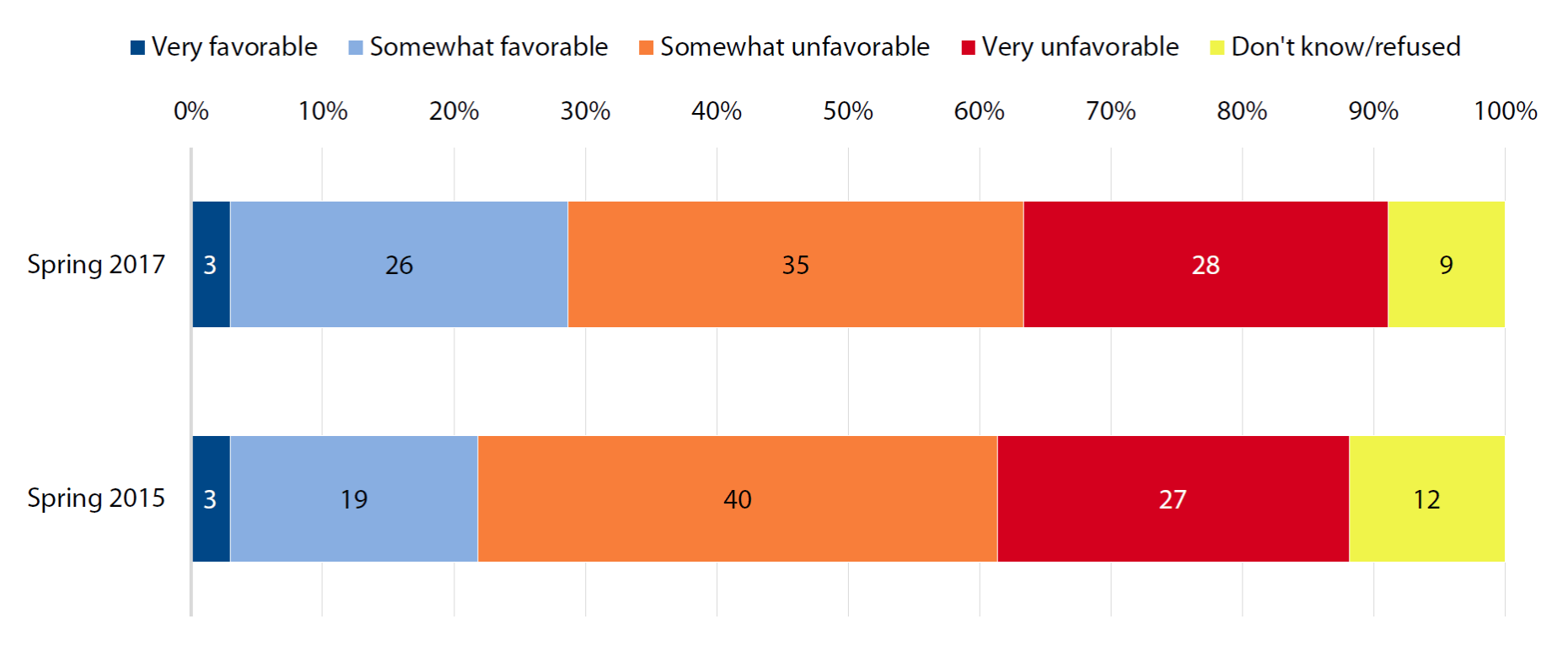

Figure 1: Please Tell Me If You Have a Very Favorable, Somewhat Favorable, Somewhat Unfavorable or Very Unfavorable Opinion of […] Russia (in % of respondents)

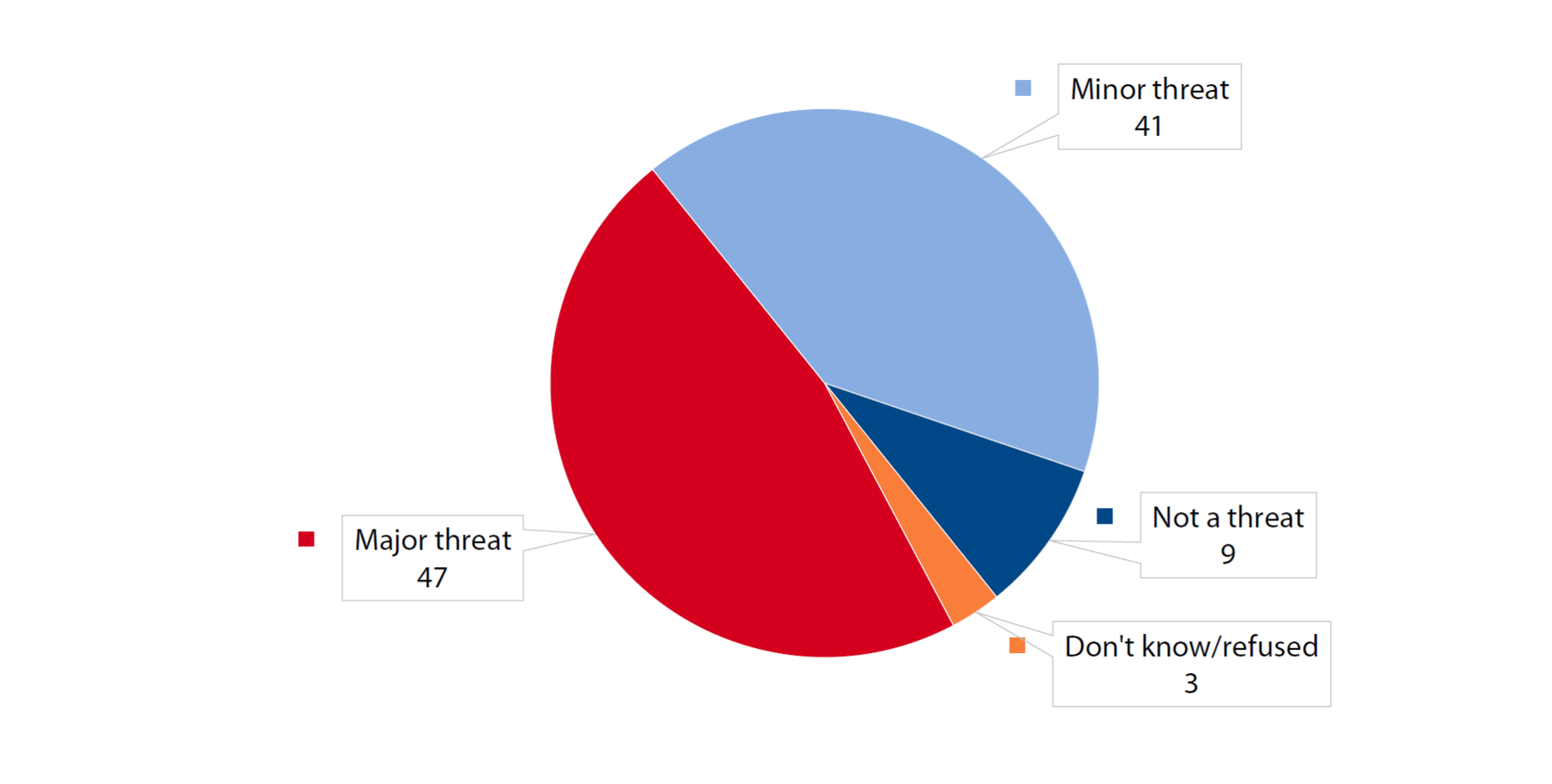

Figure 2: I’d Like Your Opinion About Some Possible International Concerns for the US. Do You Think That Russia’s Power and Influence Are a Major Threat, a Minor Threat or Not a Threat to the US? (in % of respondents)

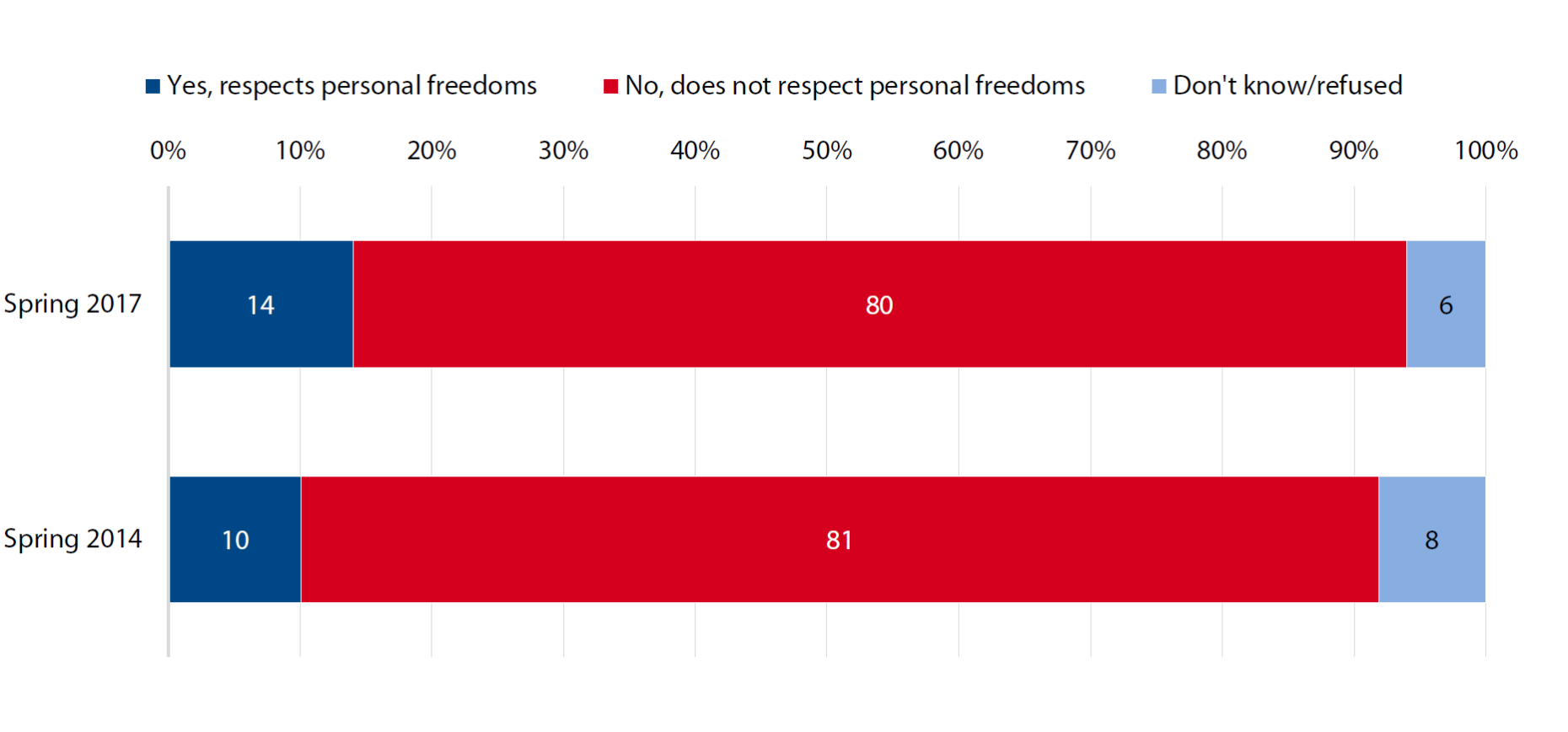

Figure 3: Do You Think the Government of Russia Respects the Personal Freedoms of its People or Don’t You Think So? (in % of respondents)

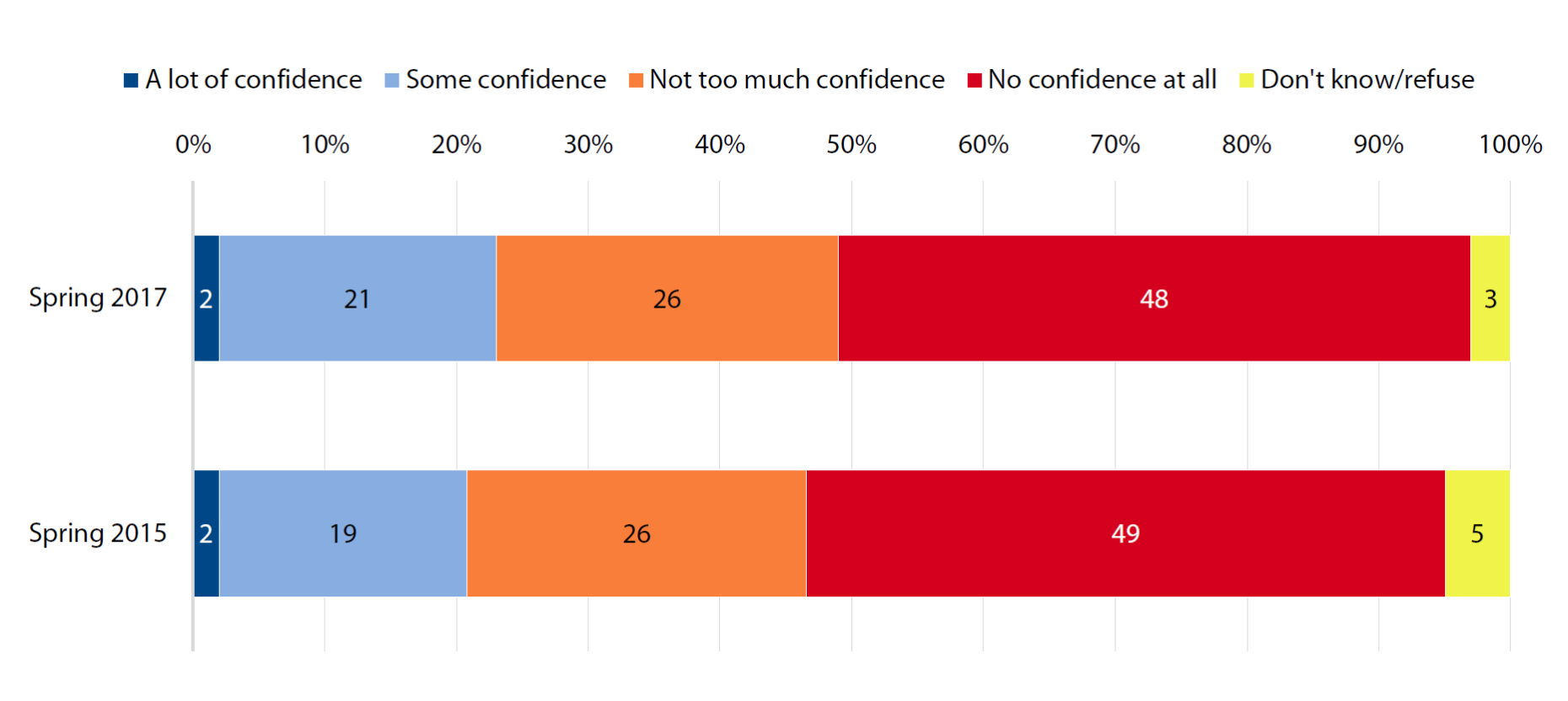

Figure 4: Tell me How Much Confidence You Have in Russian President Vladimir Putin To Do the Right Thing Regarding World Affairs—a Lot of Confidence, Some Confidence, Not Too Much Confidence or No Confidence At All. (in % of respondents)

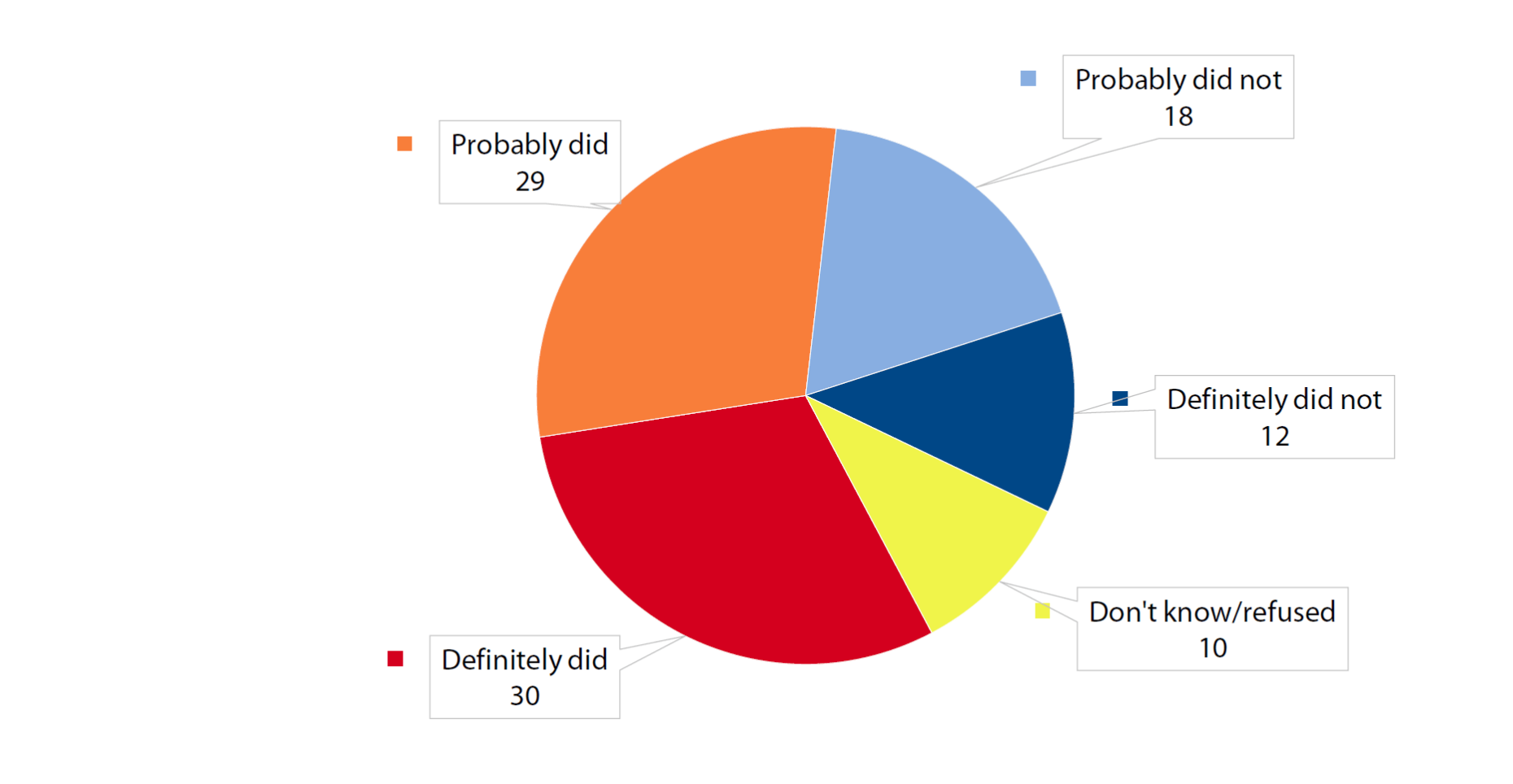

Figure 5: Thinking About the Investigation into Russian Involvement in the 2016 Election … Just Your Impression, Do You Think Senior Members of the Trump Administration Definitely Did, Probably Did, Probably Did NOT or Definitely Did NOT Have Improper Contact with Russia During the 2016 Presidential Campaign? (in % of respondents)

Carl Schmitt in Moscow: Counter-Revolutionary Ideology and the Putinist State

David Lewis (University of Bradford, Bradford)

Abstract

Far from being a regime devoid of ideology, much of Russia’s political elite shares ideas and concepts that together constitute a consistent worldview based on anti-liberal and counter-revolutionary premises. Its basic categories, interpretations and concepts share important affinities with the constitutional and political theories developed by German jurist Carl Schmitt. Russian conservative thinking on the nature of sovereignty, the definition of the nation, theories of democracy, and emerging conceptualizations of international order all show remarkable overlaps with Schmittian anti-liberalism, but Russia’s recent political development also demonstrates the inevitable shortcomings of authoritarian anti-liberal ideologies in the 21st century.

Post-Soviet Russia is often viewed as a state without ideology, an unprincipled kleptocracy primarily designed to fuel the offshore bank accounts of a rapacious elite, but without any underlying political principles. But no political system can exist for long without a set of ideas and concepts that are shared by a large part of the political elite. There are many ways to interpret this ‘Putinist’ mode of thinking about the world, but some of the most productive insights emerge through comparisons with German conservative thought of the interwar period, notably the work of the jurist Carl Schmitt (1888–1985), who has become one of the most important influences on Russian political thinking in the early 21st century.

Schmitt was a brilliant scholar, whose critiques of political liberalism have become increasingly influential in political theory, but his reputation is forever tainted by his membership of the Nazi party, his anti-Semitism, and his role as a jurist in the Third Reich. He became an inspiration for the European New Right, and subsequently a major intellectual influence on Russian far right conservatism, through figures such as Alexander Dugin. Dugin’s early geopolitical polemics, and his later neo-imperialist and authoritarian ‘Fourth Political Theory’, are heavily reliant on his interpretations of Schmitt. But the impact of Schmittian thinking in Russia is much broader and less explicit than its articulation by controversial figures such as Dugin. A more nuanced way to understand Schmitt’s influence in Russia can be found in Russian scholarly work on Schmitt, such as the prolific output of Alexander Filippov, professor at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics and editor of Russian Sociological Review. Filippov has translated many of Schmitt’s most important works, while using his own commentaries and critical articles to hint at parallels to contemporary Russian realities. Rather than the crude polemical use of Schmitt’s ideas, it is these more subtle affinities and overlaps between Schmitt’s conceptual universe and the contemporary world of Russian political thinking that offer productive insights.

These affinities are multiple, but four of Schmitt’s principal ideas are particularly relevant to understanding the ideological universe of contemporary Russian political thought.

Sovereignty and the Exception

No political concept was more central to Russian political discourse in the 2000s than sovereignty, but it was often understood as the need for Russia to regain its international status or to ensure a monopoly of legitimate violence throughout its territory. Schmitt defines sovereignty in a different way, however, as a monopoly of decision-making. In the pluralistic state, argues Schmitt, there are too many sovereigns—too many actors who are able to take substantive decisions, fatally undermining the state. Schmitt saw this dysfunctional pluralism in the 1920s Weimar Republic, but there were obvious parallels in 1990s Russia, when regional leaders, an unruly parliament, organized crime bosses, and a new generation of oligarchs all undermined the monopoly of the state over decision-making. Schmitt argued for an authoritarian sovereign leader who can take radical decisions, if necessary outside the constitution and the law, for the good of the people.

Putin’s first term in office was characterized above all by the removal of autonomous decision-making power from other political and economic actors. The arrest of Mikhail Khodorkovsky in 2003 completed the removal of oligarchs from participation in political decision-making. Parliamentary elections in December 2003 marked the taming of the State Duma, with the introduction of a ‘managed democracy’ that has been retained in Russia ever since. Regional leaders—encouraged to ‘take sovereignty’ in the 1990s—lost their autonomy in a series of centralizing moves, culminating in the abolition of gubernatorial elections in late 2004.

But Schmittian sovereignty is not merely about a recentralization of power. The sovereign leader, claims Schmitt in his famous aphorism, is the one who ‘decides on the exception’, the leader who can break the rules and act in an extra-constitutional capacity (Schmitt, 1985). This mode of exceptionality has become central to the functioning of the Putinist state. Both during and after the Second Chechen War, Chechnya became a semi-permanent space of exception, where Russian laws and constitutional norms did not apply. In the rest of Russia, however, the rule of law was also subordinate to political decisions, despite Putin’s early calls for the development of a law-based state. The Schmittian sovereign cannot be constrained by the courts or legal norms. The Russian judicial system therefore became permeated by exceptionality to permit the state to circumvent due process in criminal prosecutions, whenever serious political issues were at stake.

In international affairs, the assertion of sovereignty also followed a Schmittian logic. For Schmitt, international law was simply the codification of asymmetric power relations: true sovereignty resides in the ability of a political leader to violate international norms and laws in the national interest. Russia’s intervention in Georgia in 2008 and the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Federation in 2014 were clear violations of Georgian and Ukrainian sovereignty under international law. In Schmittian terms, however, both acts were an assertion of Putin’s own sovereignty, his capacity to create the exception, to act outside international law, and to create new legal realities through the exercise of military power and the appropriation of territory.

Friends, Enemies and the Political

Schmitt’s second big idea is that real politics is not about endless discussions in parliaments or electoral competition among different parties. What Schmitt terms ‘the political’ is something much deeper, a process of defining the boundaries of a political community by dividing the world into ‘them’ and ‘us’, by asking the fundamental question—who is our ‘enemy’? Defining the enemy does not necessarily mean going to war—although that is an ever-present possibility. Rather, the definition of the enemy shapes who we are as a political community. A nation needs to constantly remind itself of its enemies to ensure its own identity, and ultimately its survival.

Since the mid-2000s Russia officials have portrayed the US as an opponent posing an existential threat to the Russian state. The ‘color revolutions’ in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan were interpreted as precursors to a Western-backed revolution in Russia. New laws codified this identification of the enemy: By 2017 more than 150 organizations had been registered as ‘foreign agents’; a May 2015 law banned ‘undesirable’ international organizations, perceived as posing a threat to Russian national interests. The government imposed new restrictions on foreign travel for over four million civil servants, and for police, military, and emergency services (Lipman 2015). The anti-American narrative was fueled by state-sponsored documentaries and prime-time programs such as Dmitry Kiselev’s weekly show, Vesti nedeli. Media manipulation had an impact on public opinion. In June 2016 in a Levada poll some 78 per cent of Russians identified the US as Russia’s primary enemy, up from only 26 per cent in 2010.

Thinking in crude binaries about friends and enemies not only damages international relations, it also has the inevitable effect of ‘discovering’ internal enemies at home. In Russia, the idea of the ‘fifth column’ shifted from the conspiracy theories of marginal ultra-nationalist groups to being a central trope in mainstream discourse, even used by President Putin in his March 2014 ‘Crimea’ speech. Far-right polemicists in Russia have gone on to develop the concept of a ‘sixth’ or even ‘seventh’ column, an increasingly pathological view of society as completely penetrated by aliens and traitors. Paradoxically, rather than achieving its goal of uniting the nation through a clear distinction between ‘them’ and ‘us’, Schmittian thinking only threatens a vicious spiral into greater division and polarization, symbolized by the murder in February 2015 of Boris Nemtsov, who had been repeatedly labelled a ‘fifth columnist’ by nationalist activists.

Illiberal Democracy

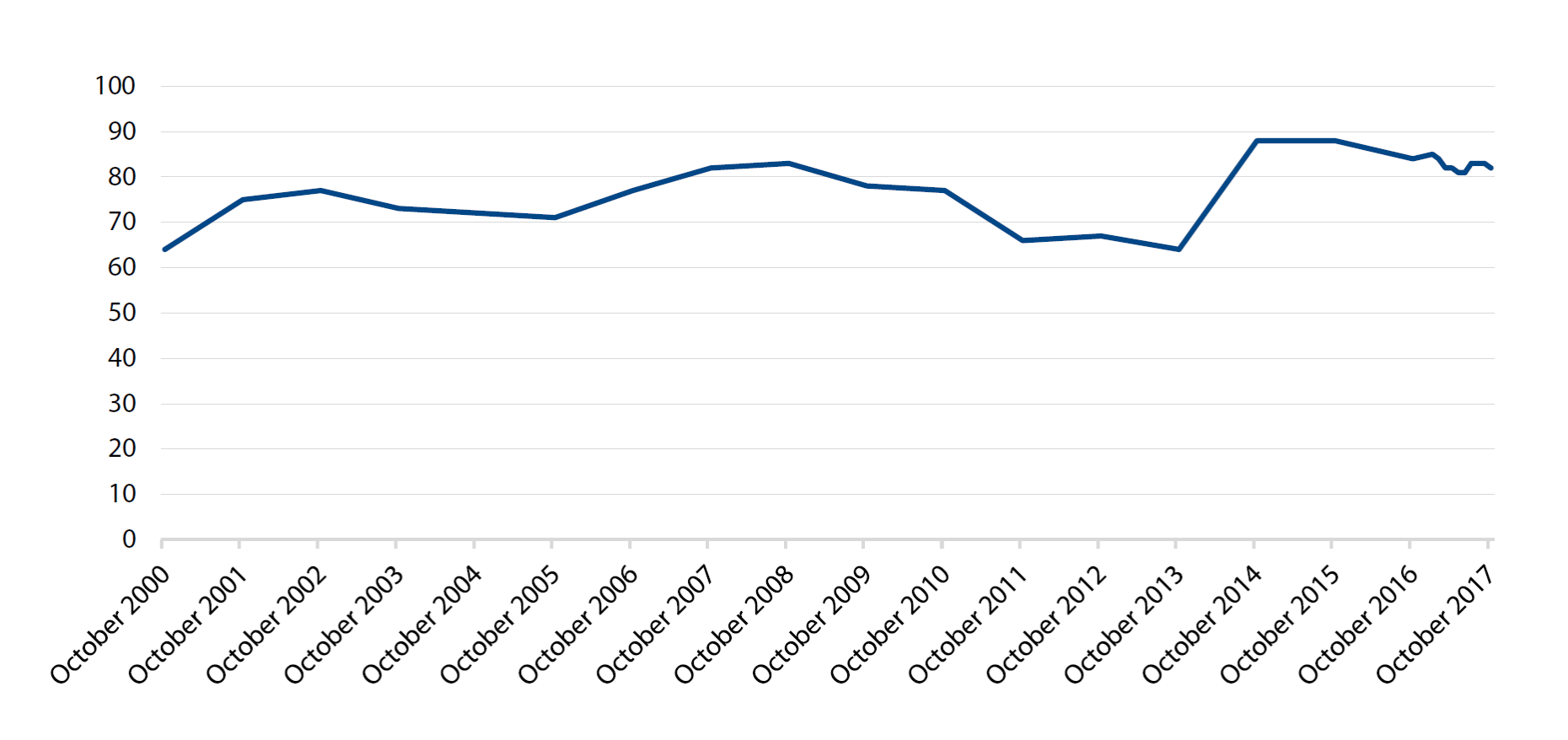

The identification of the enemy informs Schmitt’s third conceptual move—the separation of democracy from liberalism. For Schmitt, liberal democracy is an oxymoron—liberal norms such as the rule of law prevent the people from truly expressing their collective will. Instead, Schmitt seeks a kind of authoritarian democracy, in which the ruling elite and a united people develop a common identity and common interests. Schmittian democracy is not a contest between different political parties, or a mechanism for managing conflicts in society, but the creation of an almost mystical connection between the leader and the masses. In Russia, elections long ago lost any element of surprise, but public opinion—and public acclamation of the leader—still remain important to the regime. Opinion poll ratings for President Putin—which have remained above 80 per cent since the Crimean events in the spring of 2014—are viewed as a leading indicator of regime stability. The authorities seeks to both shape and reflect the views of an ‘overwhelming majority’ of Russian society, constructing a unified public consensus, while limiting political representation for minority political views and social identities. This illiberal understanding of democracy was clearly articulated in Vladislav Surkov’s notion of ‘Sovereign Democracy’, an ideological project strongly influenced by Schmittian ideas. Although the term disappeared from public usage, the basic principles of the system have remained in place. The regime seeks to retain public support, while denying any subjectivity for the people in deciding its own political future.

Großraum-Thinking and International Order

A final area of affinity between Russian realities and Schmittian theories is in international relations. Schmitt views liberal, universal norms, such as ‘human rights’ or ‘democracy’, as mere window-dressing for the power politics of US imperialism. But Schmitt also argued that international order cannot revert to strict Westphalian conceptualisations of sovereignty. Instead, in a new multipolar order Great Powers will establish new spheres of influence, or Großraüme [‘Great Spaces’], characterised by the presence of a ‘politically awakened nation’, a ‘political idea’, and the absence of what Schmitt terms ‘spatially alien powers’ from this space (Schmitt, 2011). Schmittian geopolitics underpins much of the neo-imperialist thinking on the Russian far right, but elements of Großraum thinking can also be identified in official discourse.

Moscow increasingly views the world as dividing into major political-military-economic blocs, and much of Russian foreign policy is determined by the need to ensure Russia’s centrality to one of these ‘world-regions’. Hence the ‘Eurasian turn’ in Putin’s third term in office, institutionalized in the troubled Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), but also articulated since 2015 in terms of ‘Greater Eurasia’, a term that has a varied geography, but serves the purpose of putting Russia at the heart of a region stretching from Eastern Europe and the Black Sea in the West, through the Middle East and Central Eurasia, across to China in the east.

Not only does Russia view itself as a reviving power with historical rights and duties in this ‘Great Space’ of Eurasia, but it also imbues its presence in the region with a political idea, a mix of traditional conservative norms and views of appropriate forms of political order that together constitute a kind of ‘Moscow Consensus’ among regional states. From Kyrgyzstan to Ukraine, Russian foreign policy has focused on excluding Western powers from this ‘sphere of special interests’, and views Western influence in states such as Georgia and Ukraine as an existential threat to Russia itself. Eurasia is presented as a coherent region with its own culture and values, a civilizational space where Western liberal values are not appropriate. Russia’s centrality to the emergence of a new Eurasian space, however, leaves little room for the sovereignty of other smaller powers, but Russia’s neighbors will not easily acquiesce in the reassertion of Russian hegemony in the region.

Conclusion

Schmitt’s intellectual influence is hardly limited to Russia. The multiple failures of the post-Cold War liberal project, not only in Russia, but internationally, have provoked a counter-revolutionary wave. Anti-liberalism is in vogue globally, and Schmitt provides its most sophisticated intellectual voice. Studying Russia’s ideological twist towards illiberalism, therefore, has important implications for global politics. Schmitt’s critique of liberalism is often potent and the interest in Schmitt’s work in Russia is understandable in response to a crisis of post-Soviet Russian statehood. But Schmitt’s political alternative to liberalism is an ultra-conservative project promoting authoritarian sovereign power, illiberal democracy, sharp boundaries between communities, and an international order dominated by Great Powers. Russia’s experience already demonstrates the shortcomings of such an authoritarian political turn. An ideology of pure sovereignty offers no defense against bad political decisions and no mechanisms to check the endemic corruption and poor governance that exceptionality promotes. Defining the world solely with reference to friends and enemies polarizes society, legitimizes violence and repression, and makes minorities vulnerable. And a world characterized by spheres of influence and Great Power politics has no space for the sovereignties of small states, and a high risk of the resumption of major power war. Schmitt has little to say about economic, social and technological modernization, or about overcoming deep-rooted conflicts and tensions in society. Yet his identification of the emotional appeal of decisionist authoritarianism in times of turbulence suggests that the neo- Schmittian revival will continue to influence politics in Russia and beyond for some time to come.

References

Lipman, Maria, ‘The Undesirables’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 22 March 2015, <http://www.ecfr. eu/article/commentary_the_undesirables3041>

Schmitt, C. (1985) Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. by George Schwab (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Schmitt, C. (2011) ‘The Großraum Order of International Law with a Ban on Intervention for Spatially Foreign Powers: A Contribution to the Concept of Reich in International Law (1939–1941’), in C. Schmitt, Writings on War, trans and ed by Nunan T. (Cambridge: Polity): 75–124.

About the Author

David Lewis is a Senior Lecturer at University of Exeter, UK.

Russian Public Opinion on Putin and on the USA

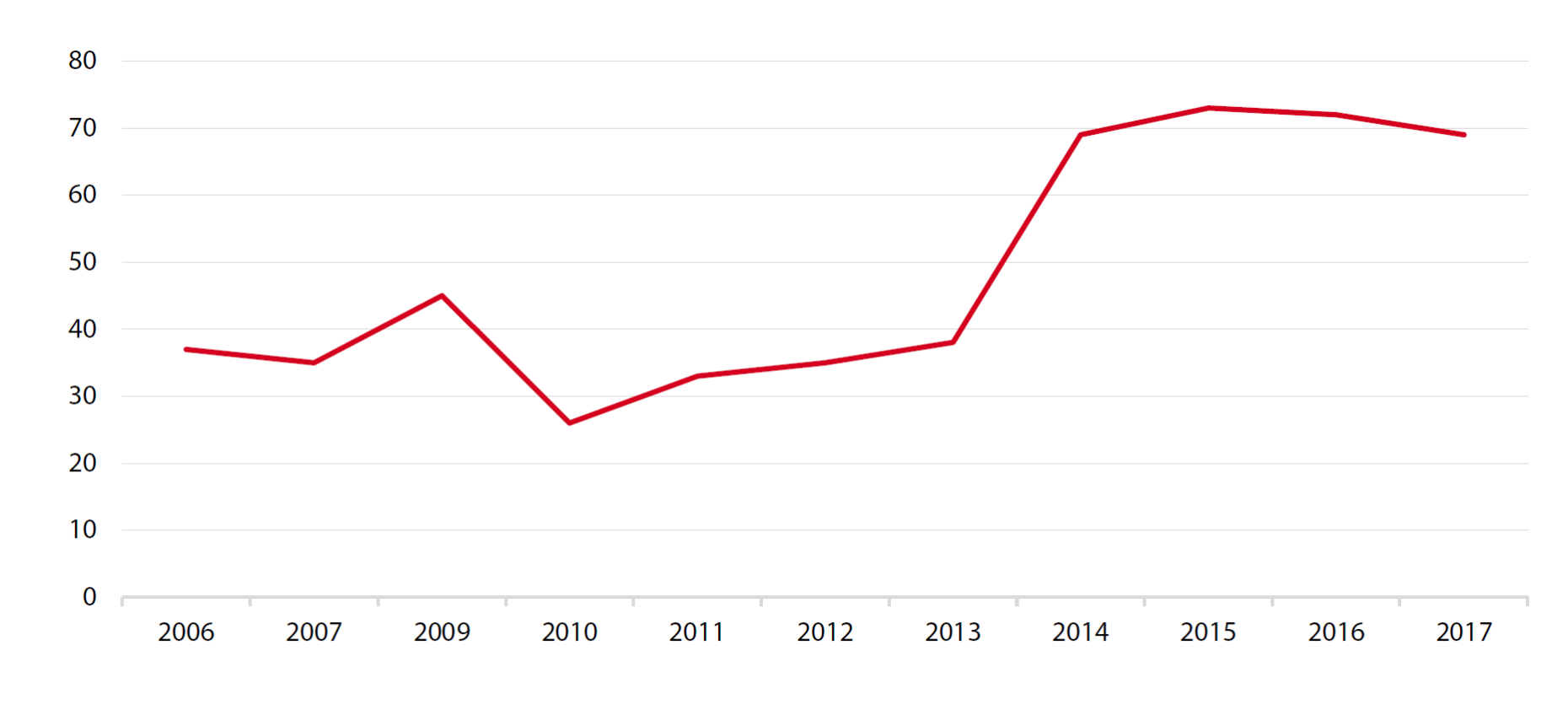

Figure 1: On the Whole, Do You Approve or Disapprove of the Work of Vladimir Putin as President of Russia? (% of respondents who answered “Approve”)

Figure 2: Which Five Countries Do You Think Have the Most Unfriendly and Hostile Attitude Towards Russia? (only % of respondents who answered “USA”)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.